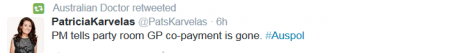

It wasn’t a good start for Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s new, improved government after he survived the Liberal party room spill motion, with confusion from the get go about whether or not the GP co-payment proposal was finally going the way of his knighthood selections and the Parental Payment Scheme.

The word, at least for now, seems to be that Health Minister Sussan Ley (who officially joined the not very diverse frontbench today, see the pic below) will consult very closely with doctors, but not necessarily with others who have plenty of evidence about priorities and the impact of the copayment in particular.

Welcoming the central role, the AMA has called in a statement for the Government to “end the uncertainty” about its Medicare plans.

“The Prime Minister must ditch the disastrous Medicare co-payment model, the $5 cut to the Medicare patient rebate, and the freeze on Medicare rebate indexation until 2018.”

AMA president Brian Owler said the grassroots message from AMA doctor forums in several States yesterday was clear: “The Government must scrap its potentially destructive Medicare changes. All of them.”

This post below, from Brooke McKail, policy adviser at the Victorian Council of Social Service (VCOSS), looks through the recently published Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services to show the health pressures on many vulnerable Australians, for whom the cost of health care is already too high. Thanks to VCOSS for permission to repost the article from its blog.

Also of interest is this report of last week’s Senate committee hearings where the Health Department admitted that it failed to conduct in-depth analysis or research on the social impact of co-payments before the Federal Government announced its policy.

And see at the bottom of the post for more Twitter reaction to the copayments issue today.

***

Brooke McKail writes:

Cost and delays are barriers to healthcare for too many Victorians

One third of Aboriginal Victorians deferred purchasing prescription medications because of cost in 2013-14, and 1 in 8 deferred going to the doctor, a new report shows.

This compares with 1 in 20 Victorians in general who deferred going to the doctor due to cost.

The figures, in the most recent volume of the Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services, show that cost is already causing significant numbers of people to delay seeking healthcare. This may worsen if the Australian government goes ahead with plans to increase Medicare co-payments.

The report also shows that good health and access to healthcare in Victoria remains unequal, and that the availability of public dental care is lower than in other states.

People in lower socioeconomic groups and Aboriginal Victorians are most likely to experience mental ill-health. Waiting times for public dental services are again on the increase, particularly for disadvantaged Victorians.

Positively, the data showed Victoria’s bulk billing rates remain high. Having more GP services that bulk-bill improves access to healthcare for vulnerable Victorians.

Oral disease is a significant health issue in Victoria and is one of the most underfunded areas of healthcare. The disease is experienced at a greater rate by people experiencing disadvantage, including Aboriginal people, people on low incomes and people in rural and regional areas.

According to the report, Victoria has a lower rate of public dentists than the national average, at 6.2 per 100,000 Victorians. We also have the lowest rate of public dental hygienists and dental therapists.

Waiting times for public dentistry have increased significantly in the last year. Despite success in reducing public dental waiting lists through the National Partnership Agreement (NPA) on Public Dental Health Services, the deferral of this agreement may be causing waiting times to grow again. In 2012-13 around 70 per cent of people waited more than one month for services. By 2013-14 this had risen to 83 per cent (the second highest percentage nationally).

The Victorian government could ensure waiting lists do not blow out to the levels seen before the NPA, by expanding community dental facilities and increasing the availability of vouchers for people to see private dentists.

The report shows that the most disadvantaged people in our community bear the greatest burden in ill-health. People in the lowest socioeconomic group are more than twice as likely to have high or very high levels of psychological distress, than people in the highest income range. People with mental health problems were also significantly more likely to be overweight or obese, to smoke tobacco daily and to be at risk of long-term harm from alcohol.

Primary and community health services are often the first point of contact for vulnerable people needing care. In the last two years, there has been a drop in real expenditure per person on specialised mental health services in Victoria. Primary and community health services also receive proportionately less of the Victorian health budget than they did 10 years ago. The state government can help improve the health of Victorians by increasing the proportion of health funding that goes to community health, including community mental health support services, and alcohol and other drug treatment services.

Aboriginal people are also at higher risk of mental ill-health. The report showed they are three times as likely as non-Aboriginal people to have high or very high levels of psychological distress.

These data confirm the need for Aboriginal community controlled services to have additional resources to provide mental health services to Aboriginal people. Despite increases in funding to Aboriginal controlled services for other health areas, funding for mental health services has not increased. The state government can help close the gap and improve Aboriginal people’s mental health and wellbeing by increasing funding targeted to mental health specific programs within Aboriginal community controlled health organisations.

***