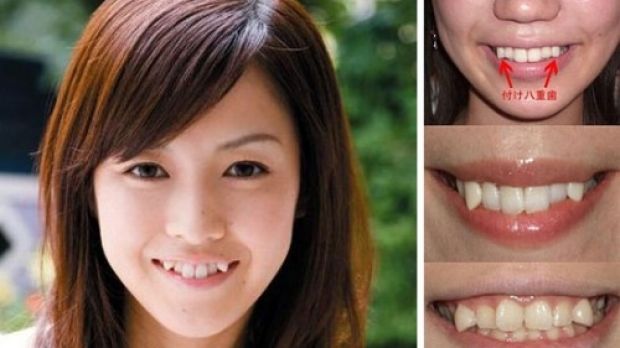

Cute? The snaggletooth trend has been growing in Japan. Photo: Tumblr

It’s a beauty trend that has some experts worried. But is it as bad as it’s being made out to be?

The snaggletooth trend has been growing in Japan in the past few years.

It involves young girls paying to have their perfectly normal teeth turned into fangs.

Gap year: Australian model Jessica Hart and her instantly recognisable look. Photo: Theo Wargo

“Japanese women of all ages [are] flocking to dental clinics to have temporary or permanent artificial canines … glued to their teeth,” reports Japan Today.

Why?

Snaggletooth, or yaeba, as it’s otherwise called, “gives girls an impish cuteness”, according to one Japanese dentist who offers the procedure.

Sounds no more harmful than any other beauty trend, many of which might be referred to as odd if we take a good, long look at them.

So what’s the problem?

“The naturally occurring yaeba is because of delayed baby teeth, or a mouth that’s too small,” Emile Zaslow, an associate professor specialising in media and identity told the New York Times. “It’s this kind of emphasis on youth and the sexualisation of young girls.”

Sydney dentist Dr Steven Lin agrees that the procedure emulates a look commonly found in young teenagers.

“People seem to be drawn to these type of procedures because it mimics a development period that occurs during youth and hence may give the appearance of being younger,” he says.

Lin, who says the only real physical risk is developing a lisp from having such a procedure done, says the trend has not caught on in Australia.

“The Western equivalent would be the ‘London Gap’, which has been made famous by models such as Lara Stone and Australia’s own Jessica Hart,” he says. “In Australia I’ve been consulted by patients to who wish to emulate the ‘London Gap’ – not something that I recommend.”

Be it the ‘London Gap’ or the snaggletooth, these trends towards looking ‘cute’ or even imperfect, are the same Zaslow argues.

“It’s not based in self-acceptance,” she says. “It’s still women changing their appearance primarily for men.”

Professor Catharine Lumby of Macquarie University, who specialises in gender and media studies, thinks we shouldn’t be too quick to judge.

“Whenever we think about how women present themselves, we need to take a whole range of things into account,” she says.

“Class, cultural background and cultural norms are important things to understand.”

Japan, for instance, has a whole set of cultural practices – which include the Hello Kitty/ cutesy fetishisation of youthfulness -that “from a Western perspective, are often misrepresented and misunderstood.

“You can’t transfer them onto an Australian teenager.”

Where the argument is transferable, she suggests, is the discussion about how we play with and present our sexuality.

“It’s a complex area, but it’s not about policing young women – that there are slutty, working girls or respectable middle class ones,” says Lumby, who argues that beauty or fashion trends often become class-based debates.

Just because a teenager or young women gets her teeth turned into fangs, has a gap chiselled into her front teeth or wears a crop top and gyrates to Wrecking Ball, doesn’t mean she’s going to hell in a handbasket.

“There’s always been subcultural trends,” Lumby points out. “In the ’90s there was tattoos and piercings, now it’s gone mainstream.”

The snaggletooth and gap-tooth trends are just other examples of such expression and exploration of sexuality.

Despite concern that such expression is sexualising young girls, “there just isn’t evidence that’s happening”, Lumby says. She points to research indicating that the age teenagers are losing their virginity hasn’t significantly changed.

Instead of “talking about them in an anxious fashion”, Lumby says the conversation about what young girls – and boys – are doing should shift to how to educate them better, provide them with choices and teach them about sexual health.

“Why don’t we give women more choices,” she asks, “and bring young women into the conversation.”

As far as the gap-tooth goes, it might not be to everyone’s taste but who cares, Lumby says.

“No doubt, in 10 years, they’ll get that filled in.”