The first batch of an experimental Ebola vaccine has been shipped to West Africa where it will be used in large-scale trials in coming weeks, providing a glimmer of hope for public health officials working to stem the spread of the disease. Healthcare workers helping to care for Ebola patients will be among the first to get the vaccine when trials start. Researchers hope to eventually enroll up to 30,000 people in the trial.

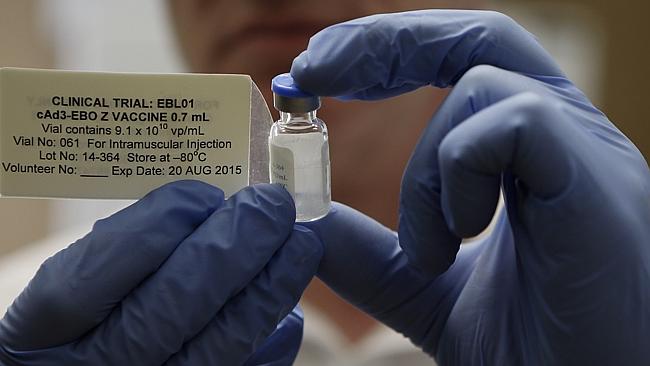

The vaccine, co-developed by the National Institutes of Health in the United States and Okairos, a biotechnology firm acquired by UK drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) in 2013, was shown in initial testing to be safe and effective at producing a response from the immune system. The question is whether that response will protect vaccinated health workers and burial teams from infection or enable them to fight off the disease.

The trial is being carried out by the National Institutes of Health, which will vaccinate 30,000 people. Only one-third will get the candidate vaccine; others will get a routine vaccine against another disease, such as measles. The investigators will be looking to see whether there are further cases of infection in the control group than among those who were given the potential Ebola vaccine.

The vaccine uses a type of chimpanzee cold virus to deliver safe genetic material from the Zaire strain of Ebola, the strain responsible for the unprecedented West African epidemic.

Another vaccine, from Merck and NewLink, is also set to be tested in Liberia. In December, trials of that vaccine were stopped after some of the volunteers in the trial had “transient mild” joint pain. After investigating that side effect, scientists concluded it was not a big enough issue to stop the development of the vaccine. No similar side effects were noted in the GSK trial. There are other Ebola vaccines being tested by companies in the United States and in Russia.

GSK sent an initial shipment of 300 vials of vaccine ahead of the rollout of a mass clinical trial. Health care workers in the country to help care for Ebola patients are expected to be among the first to receive the drug. The disease has killed hundreds of doctors and nurses in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea — the three worst hit Ebola-affected countries — taking a severe toll on the health care systems of West Africa.

Sierra Leone has seen the most cases of the virus, but Liberia leads the three in number of deaths at 3,605, according to latest World Health Organization (WHO) figures. The disease spread quickly this summer through the country’s capital Monrovia, where poverty and lack of sanitation helped quicken transmission.

The vaccine arrives at a crucial time in the fight against Ebola, with health officials fearing that the April-May rainy season will hamper efforts to fight the outbreak in remote regions.

No scientifically proven cure or vaccine exists for the virus — a reality health officials hope to change in the near future. The only known way to manage Ebola is through supportive care, such as intravenous hydration to treat symptoms like severe diarrhea and vomiting that can cause loss of fluids.

Some health care workers have been given blood transfusions from Ebola survivors to help treat the virus, but because the method has not undergone clinical trials its effectiveness is uncertain. Some have survived with, or perhaps despite, the therapy. Others have not.

Releasing a drug or vaccine for public use can take up to a decade in some cases, but with the rapid spread of Ebola last year and the heavy death toll that accompanied it, the government allowed a shortened timeline. Still, clinical trials for a vaccine will take at least nine months.

The WHO said Thursday that the West Africa Ebola outbreak, the worst in history, appears to be waning, but it cautioned against complacency. The epidemic has seen 21,724 cases reported in nine countries since it started in Guinea a year ago. Some 8,641 people have died.