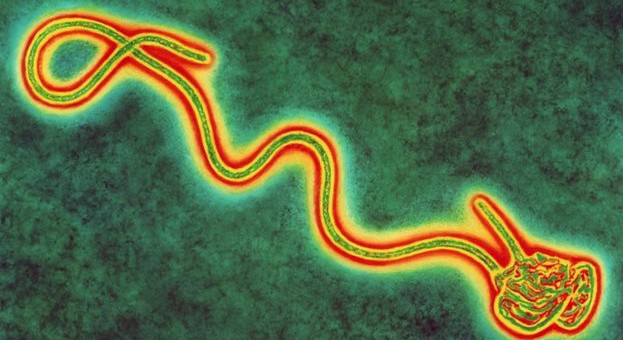

Scientists are warning that the effectiveness of new Ebola treatments could be compromised by recent mutations to the virus.

After tracking the genetic mutations that have occurred in the Ebola virus during the last four decades, researchers identified changes in the current West African outbreak strain that could potentially interfere with experimental, sequence-based therapeutics that are currently in development.

The team published their findings Tuesday in mBio, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

“We wanted to highlight an area where genomic drift, the natural process of evolution on this RNA virus genome, could affect the development of therapeutic countermeasures,” says Gustavo Palacios, senior author of the study and director of the Center for Genome Sciences at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) in Frederick, Maryland.

Many of the most promising drugs being developed to fight Ebola are therapeutics that bind to and target a piece of the virus’s genetic sequence or a protein sequence derived from that genetic sequence. If that sequence changes due to genetic drift, the natural evolution of the virus over time, then the drugs may not work effectively.

“Our work highlights the genetic changes that could affect these sequence-based drugs that were originally designed in the early 2000’s based on virus strains from outbreaks in 1976 and 1995,” says Palacios.

Mutations detected in 3 percent of Ebola genome

The team compared the entire genomic sequence of the current outbreak strain, called EBOV/Mak, with two other Ebola virus variants–one from an outbreak in Yambuku, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1976 called EBOV/Yam-May, and one from an outbreak in Kikwit, Zaire in 1995 called EBOV/Kik-9510621. They found changes, called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, in more than 600 spots, or about 3 percent of the genome.

The sequence-based drugs currently offer the best hope for future treatment of Ebola outbreaks, but have not yet been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration or any other regulatory agency. Because the World Health Organization (WHO) adopted emergency containment measures for the ongoing West African outbreak, these drugs are currently being used to treat a few handfuls of patients in experimental testing. A clinical trial for one of the therapies will begin in Sierra Leone in the coming weeks.

The team, which included researchers from USAMRIID, Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then narrowed their search to only those mutations that changed the genetic sequences targeted by the various drugs. Of those, they found 10 new mutations that might interfere with the actions of monoclonal antibody, siRNA (small-interfering RNA), or PMO (phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer) drugs currently being tested. This includes the experimental drug ZMapp, one of the most promising Ebola therapies under development.

The authors conclude that drug developers should check whether these mutations affect the efficacy of the therapeutic drug.

“The virus has not only changed since these therapies were designed, but it’s continuing to change,” says US Army Captain Jeffrey Kugelman, lead author and a viral geneticist at USAMRIID. Three of the mutations the team found appeared during the ongoing West African epidemic. “Ebola researchers need to assess drug efficacy in a timely manner to make sure that valuable resources are not spent developing therapies that no longer work.”

Virus rapidly mutating as it spreads

According to the latest data from the WHO, more than 21,600 cases of Ebola have been confirmed in the current outbreak, of which more than 8,600 have resulted in death. Ebola is an RNA virus, which means every time it copies itself, it makes one or two mutations. This gives Ebola a very high mutation rate when compared to DNA-based viruses like smallpox or chickenpox.

A recent study of the West African Ebola outbreak — the worst in recorded history — found that the virus is evolving much more quickly than in the past. Many of those mutations mean nothing, but some of them might be able to change the way the virus behaves inside the human body, including how it responds to treatment. As Ebola continues to spread through the population, the risk of a significant mutation goes up.

“The virus mutates rapidly and it’s an ongoing concern,” said Dr. Kugelman. He is currently in Charlesville, Liberia at the Liberian Institute for Biomedical Research, working with the local government to set up onsite genomics sequencing of Ebola patient samples to get a real-time picture of how the virus changes as it is transmitted from human to human. He’ll be analyzing whether the virus’s genetic sequences that are key for diagnostic tests and drug interventions change over time.