Scientists have developed a brain-imaging technique that may be able to identify children with autism spectrum disorder in just two minutes. This test, while far from being used as the clinical standard of care, has promising diagnostic potential, offering an objective and measurable indicator of autism.

Autism is among the most common disorders of childhood, affecting an estimated 1 in 68 children in the United States. Despite the high prevalence, there remain significant challenges in making the right diagnosis and identifying the right tools to make a diagnosis. Adding to the confusion, many children who place on the autism spectrum also may have other neurological disorders, and sometimes, other neurological disorders can be mistaken for autism.

Usually, diagnosis of autism — an unquantifiable process based on clinical judgment — is time consuming and very trying on children and their families. But that may change with this new diagnostic test, which uses brain scans to map neurological differences in the perspective-tracking abilities of people diagnosed with autism versus those without the disorder.

“Our brains have a perspective-tracking response that monitors, for example, whether it’s your turn or my turn,” said Dr. Read Montague, who led the research at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute. “This response is removed from our emotional input, so it makes a great quantitative marker. We can use it to measure differences between people with and without autism spectrum disorder.”

Research indicates that the the ability to shift between one’s own perspective and that of another person is necessary for the development of social competence and social reasoning — skills that are typically underdeveloped in people with autism. By identifying the neural correlates of this ability, Dr. Montague’s team demonstrated that the brain’s perspective-tracking response can be used to determine whether someone has autism spectrum disorder. Their findings are published this week in the journal Clinical Psychological Science.

‘Middle cingulate cortex is responsible for distinguishing between self and others’

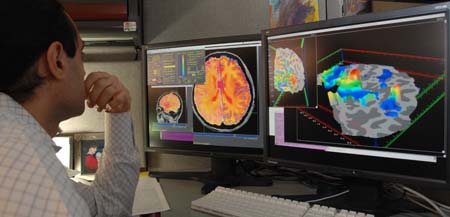

The path to this discovery has been a long, iterative one, say the researchers. In a 2006 study by Dr. Montague and colleagues, pairs of subjects had their brains scanned using functional magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, as they played a game requiring them to take turns. From those images, researchers found that the middle cingulate cortex became more active when it was the subject’s turn.

“A response in that part of the brain is not an emotional response, and we found that intriguing,” said Dr. Montague, who also directs the Computational Psychiatry Unit at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and is a professor of physics at Virginia Tech. “We realized the middle cingulate cortex is responsible for distinguishing between self and others, and that’s how it was able to keep track of whose turn it was.”

That realization led the scientists to investigate how the middle cingulate cortex response differs in individuals at different developmental levels. In a 2008 study, Dr. Montague and his colleagues asked athletes to watch a brief clip of a physical action, such as kicking a ball or dancing, while undergoing functional MRI. The athletes were then asked either to replay the clips in their mind, like watching a movie, or to imagine themselves as participants in the clips.

“The athletes had the same responses as the game participants from our earlier study,” said Dr. Montague. “The middle cingulate cortex was active when they imagined themselves dancing – in other words, when they needed to recognize themselves in the action.”

In the 2008 study, the researchers also found that in subjects with autism spectrum disorder, the more subdued the response, the more severe the symptoms.

Based on these findings, Dr. Montague and his team hypothesized that a clear biomarker for self-perspective exists and that they could track it using functional MRI. They also speculated that the biomarker could be used as a tool in the clinical diagnosis of people with autism spectrum disorder.

In 2012, the scientists designed another study to see whether they could elicit a brain response to help them compute the unquantifiable. And they could: By presenting self-images while scanning the brains of adults, they elicited the self-perspective response they had previously observed in social interaction games.

Only one image needed to identify differences in perspective-tracking response

In the current study, children were shown 15 images of themselves and 15 images of a child matched for age and gender for four seconds per image in a random order. Like the control adults in the previous study, the control children had a high response in the middle cingulate cortex when viewing their own pictures. In contrast, children with autism spectrum disorder had a significantly diminished response.

Importantly, Dr. Montague’s team could detect this difference in individuals using only a single image, providing the basis for a single-stimulus functional MRI diagnostic technique. The single-stimulus part is key, Dr. Montague points out, as it enables speed. Children with autism spectrum disorder cannot stay in the scanner for long, so the test must be quick.

“We went from a slow, average depiction of brain activity in a cognitive challenge to a quick test that is significantly easier for children to do than spend hours under observation,” said Dr. Montague. “The single-stimulus functional MRI could also open the door to developing MRI-based applications for screening of other cognitive disorders.”

By mapping psychological differences through brain scans, scientists are adding a critical component to the typical process of neuropsychiatric diagnosis — math.

Dr. Montague has been a pioneering figure in this field, which he coined ‘computational psychiatry‘. The idea is that scientists can link the function of mental disorders to the disrupted mechanisms of neural tissue through mathematical approaches. Doctors then can use measurable data for earlier diagnosis and treatment.

An earlier diagnosis can also have a tremendous impact on the children and their families, adds Dr. Montague. “The younger children are at the time of diagnosis,” he said, “the more they can benefit from a range of therapies that can transform their lives.”