A new analysis has opened the door to discovery of thousands of potential new cancer biomarkers, a finding scientists say could lead to breakthroughs in cancer diagnostics and treatment.

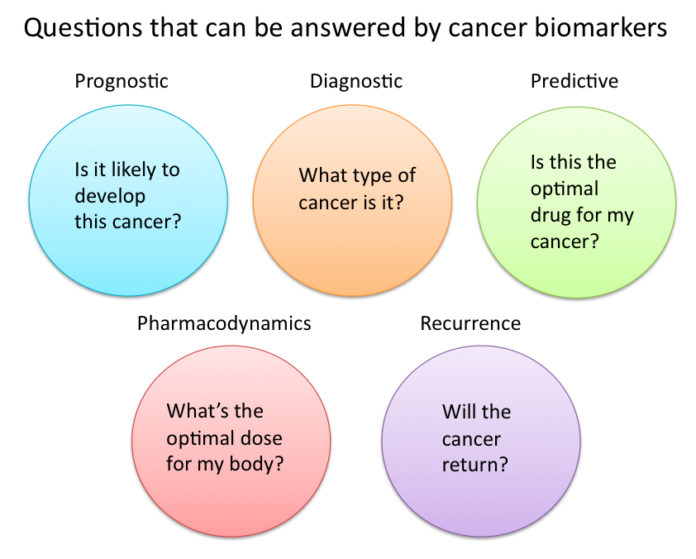

Cancer biomarkers are substances or processes that are indicative of cancer in the body. These include certain molecules secreted by tumors, gene mutations, as well as specific responses the body displays in the presence of cancer. Present in blood, tissue and serum, cancer biomarkers can be used for diagnosis and to predict the natural course of a tumor, indicating whether the outcome for the patient is likely to be good or poor(prognosis). They are also used to help doctors to decide which patients are likely to respond to a given drug (prediction) and at what dose it might be most effective (pharmacodynamics).

In recent years, scientists have discovered a host of new cancer biomarkers. The presence and expression of human epidermal growth factor receptors 2 (HER2), estrogen receptors, and progesterone receptors, for example, are common biomarkers used to differentiate breast cancer subtypes and identify the most effective treatment options. Other examples of cancer biomarkes include prostate-specific antigen (used in prostate cancer screening), BRCA1/2 germline mutations (used to estimate the risk of developing breast, ovarian, and other types of cancer), and calcitonin (used for early diagnosis of thyroid cancer).

Potential biomarkers can be identified through multiple approaches. The classic approach has been to identify candidate biomarkers based on the biology of the tumor and surrounding environment, or the metabolism of the pharmaceutical agent. With the explosion of new knowledge about tumors and advent of new technology, biomarker identification is now frequently performed using a “discovery” approach, using techniques such as high-throughput sequencing, gene expression arrays, and mass spectroscopy to quickly identify individual or groups of biomarkers that differ between cohorts.

Analysis identified 58,000 new cancer biomarker candidates

In this latest study, researchers at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center analyzed the global landscape of a portion of the genome that has not been previously well-explored — long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). This vast portion of the human genome has been considered the “dark matter” because so little is known about it. Emerging new evidence suggests that lncRNAs may play a role in cancer and that understanding them better could lead to new potential targets for improving cancer diagnosis, prognosis or treatment.

“We know about protein-coding genes, but that represents only 1-2 percent of the genome. Much less is known about the biology of the non-coding genome in terms of how it might function in a human disease like cancer,” says senior study author Arul M. Chinnaiyan, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Michigan Center for Translational Pathology and S.P. Hicks Professor of Pathology at the University of Michigan Medical School.

The researchers pulled together 25 independent datasets totaling 7,256 RNA sequencing samples. The data was from public sources such as The Cancer Genome Atlas project, as well as from the Michigan Center for Translational Pathology’s archives. They applied high-throughput RNA sequencing technology to identify more than 58,000 lncRNA genes across normal tissue and a range of common cancer types.

Results of the study are published online ahead of print in the journal Nature Genetics.

“We used all of this data to decipher what the genomic landscape looks like in different tissues as well as in cancer,” Chinnaiyan says. “This opens up a Pandora’s box of all kinds of lncRNAs to investigate for biomarker potential.”

The complete dataset, named the MiTranscriptome compendium, has been made available on a public website, www.mitranscriptome.org, for the scientific community to explore.

The researchers also identified one lncRNA, SChLAP1, as a potential biomarker for aggressive prostate cancer. SChLAP1 was more highly expressed in metastatic prostate cancer than in early stage disease. SChLAP1 was found primarily in prostate cancer cells, not in other cancers or normal cells, which gives researchers hope that a non-invasive test could be developed to detect SChLAP1. Such a test could be used to help patients and their doctors make treatment decisions for early stage prostate cancer.

“Some long non-coding RNAs tend to be exquisitely specific for cancer, while protein-coding genes are often not. That’s what makes lncRNAs a very promising target for developing biomarkers,” Chinnaiyan says. “We hope that researchers will investigate the MiTransciptome compendium and begin to nominate lncRNAs for further study and development. It’s likely that only a subset of these have true function but as a previously untapped area, it holds great promise.”