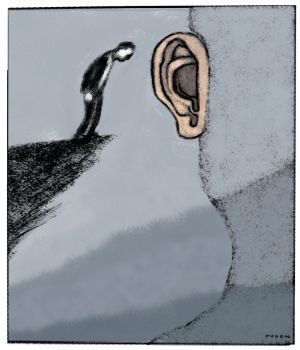

Illustration: Andrew Dyson

Driving to a meeting in 2008, Jay Lichter, a venture capitalist, suddenly became so dizzy he had to pull over and call a friend to take him to the emergency room.

The diagnosis: Meniere’s disease, a disorder of the inner ear characterised by debilitating vertigo, hearing loss and tinnitus, or ringing in the ears.

But from adversity can spring opportunity. When Lichter learned there were no drugs approved to treat Meniere’s, tinnitus or hearing loss, he started a company, Otonomy. It is one of a growing cadre of startups pursuing drugs for the ear, an organ once largely neglected by the pharmaceutical industry. Two such companies, Otonomy and Auris Medical, went public in 2014.

Big pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer and Roche are also exploring the new frontier. A clinical trial recently began of a gene therapy being developed by Novartis that is aimed at restoring lost hearing.

The sudden flurry of activity has not yet produced a drug that improves hearing or silences ringing in the ears, but some companies are reporting hints of promise in early clinical trials.

There is a huge need, some experts say. About 48 million Americans have a meaningful hearing loss in at least one ear; 30 million of them have it in both ears, said Dr Frank Lin, an associate professor of otolaryngology at Johns Hopkins University. That figure is expected to increase as baby boomers grow older.

A drug to treat or prevent age-related hearing loss “will be something that people take every day for the rest of their life,” said Edwin Rubel, a professor of hearing science at the University of Washington and co-founder of a startup called Oricula Therapeutics. “Even if it could just delay age-related hearing loss by five or 10 years, that would be wonderful.”

Of course, many people with hearing problems can use hearing aids or, for serious cases, cochlear implants. But the implants require surgery and many people do not like or use hearing aids, so drugs could be an alternative.

“Glasses can usually return you to 20/20 while hearing aids don’t return you to normal hearing, not even close,” said Kathleen Campbell, a professor at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine.

But challenges remain. Efforts in the past to develop ear drugs, to the extent they were made, largely failed. The inner ear, which is crucial to both hearing and balance, is almost impenetrable, making it difficult to study or for drugs to enter.

“It’s a teeny organ encased in a really, really hard bone,” said Dr Hinrich Staecker, professor of otolaryngology at the University of Kansas. “The whole inner ear fits inside the tip of your pinkie.”

Executives at the new companies say that genetic and animal studies are revealing more about how the ear works. They note that the pharmaceutical industry once also neglected the back of the eye. Now there are blockbuster drugs like Genentech’s Lucentis and Regeneron’s Eylea that are injected into the eye to stave off blindness from retinal diseases.

The ear, they say, is the new eye.

Crucial to hearing are about 15,000 so-called hair cells in the cochlea, part of the inner ear, which convey signals to the auditory nerve leading to the brain. The hair cells can be damaged by loud noise, by disease, by exposure to certain medicines, or simply by the passage of time. And the hair cells do not regenerate, so once they are destroyed the loss is permanent.

But maybe not for Rob Gerk, a 31-year-old man in Denver who lost most of his hearing when he had meningitis as a toddler. He is the first patient in a clinical trial of gene therapy aimed at regenerating hair cells. The trial is being sponsored by Novartis and uses a gene therapy developed by GenVec, a Maryland biotech company.

In late October, Gerk underwent surgery by Staecker at the University of Kansas to infuse viruses carrying a gene called Atoh1 into his right inner ear. Atoh1 causes cells in a foetus to become hair cells. It is hoped that some of the supporting cells in the inner ear will take up the gene and turn into hair cells.

The companies said it would take two months to tell if the therapy was working, a time period that just passed. Gerk said there was no significant change but there may have been more subtle effects. “I have incidents where I think I’m hearing a new sound or hearing sound differently than I did before,” he said by email.

Other companies are trying either to improve hearing or prevent loss of hearing from trauma like loud noises or exposure to the chemotherapy drug cisplatin or a widely used class of antibiotics known as aminoglycosides.

Auris Medical, a Swiss company, said that its experimental drug AM-111 improved hearing and speech discrimination compared with a placebo in people who were treated within 48 hours of suffering a hearing loss. But the drug was effective only for those with serious hearing loss, not mild or moderate. The drug was delivered by a single injection through the ear drum into the middle ear, from which it diffused into the inner ear.

Sound Pharmaceuticals of Seattle says its drug, intended to reduce oxidative damage to the ear, helped prevent temporary hearing loss compared with a placebo in young adults with normal or near-normal hearing who listened to four straight hours of loud music through headphones.

Autifony Therapeutics is conducting early trials of a daily pill aimed not at hair cells but at helping the brain better interpret signals from the auditory nerve.

“You can only hear what your brain allows you to hear,” said Barbara Domayne-Hayman, chief business officer at the company, which was spun out of GlaxoSmithKline and is based in Britain. “We’re basically trying to get the neurons to fire properly again.”

One sponsor of research in the area is the US Defence Department, which cannot redeploy many soldiers because they have hearing loss. At Fort Jackson, South Carolina, drill sergeant trainees fire 500 rounds from extremely loud M16 rifles over the course of 11 days. Campbell of Southern Illinois University is running a study there to test if d-methionine, an amino acid that is said to reduce oxidative damage, can help preserve their hearing.

Companies are also working on drugs for tinnitus, in which sound is perceived without a source of the sound being present. Roughly 10 per cent of American adults, or 25 million people, have experienced at least one episode lasting five minutes or more in the last year, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Tinnitus can be caused by many things, including hearing loss. Treatments include behavioural therapy and devices that can mask the sound. But many of those just help people tolerate the condition, not get rid of it. Some drugs like steroids and lidocaine are used off label.

Auris is in late-stage trials of AM-101, a derivative of the anaesthetic ketamine, which it hopes will dampen the aberrant signalling in the auditory nerve that is perceived as tinnitus. In a midstage trial, the drug, injected into the middle ear, was not more effective overall than a placebo. But a subset of patients whose tinnitus was caused by trauma or infection said the drug made the sound in their ears softer, less annoying and less disruptive of sleep.

Investors appear to be cautious given the challenges. Auris went public on Nasdaq in August at $US6 a share, using the trading symbol EARS. The stock is now trading at about $US4.

Otonomy’s stock, by contrast, has roughly doubled since its August initial public offering. That is perhaps because for now it is pursuing what might be more tractable problems.

When Lichter suffered his first attack of Meniere’s, he received steroids, a commonly used off-label treatment. But when the drug is injected into the middle ear, patients have to lie on their sides for 30 minutes and not swallow to try to keep the drug from draining into the throat through the Eustachian tube.

Otonomy, based in San Diego, developed a way to deliver the steroids as a gel that does not readily drain away after injection. The company has started the final stage of trials for the Meniere’s product. It hopes its first product – it will apply for regulatory approval in the first half of this year – could be a gel form of an antibiotic to be injected to treat middle ear infections, an alternative to eardrops.

Lichter said the intense bouts of vertigo, which left him bedridden two or three times a week, have not returned in four years. But he has constant ringing in his left ear and can barely hear through it.

Lichter, a managing director at Avalon Ventures in San Diego, said that although he had helped start 15 or 20 companies, “This is the one that is special to me.”

The New York Times