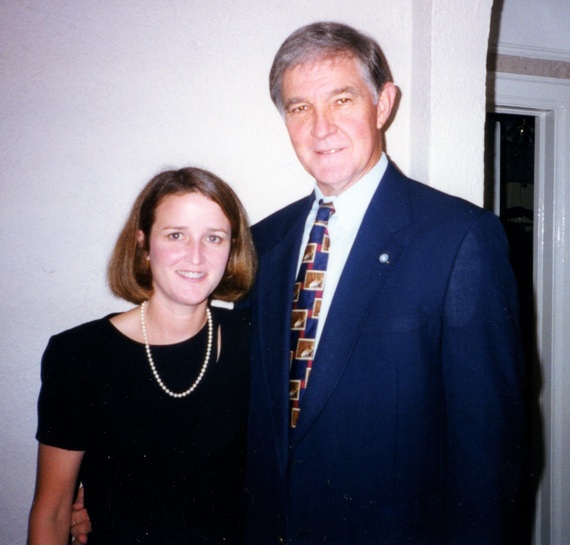

Image credit: Laura Riedel

Kathy and Gary Brewer shortly before their marriage in 1998. That same year he developed the rare illness that led to his death in 2007.

(Published originally in the Washington Post)

It wasn’t until she read her husband’s autopsy report that Kathy Brewer learned his diagnosis — a disease so rare that not one doctor had figured it out. His illness began in 1998, the year Kathy, then 38, and, Gary Brewer, then 58, got married. But Gary was busy with his job as a school superintendent in DeRidder, Louisiana and paid little attention to his backaches and knee pain, chalking them up to overexercising. Eventually, though, those first symptoms led to constant fatigue and nausea, facial numbness, congestive heart disease and kidney failure. Three years after receiving a kidney transplant, Gary couldn’t walk or swallow. Several of his organs shut down, and he died in 2007.

The cause was Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD), one of 7,000 diseases tracked by the National Organization for Rare Disorders. The National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration call such ailments “orphan” diseases because they each affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

ECD is among the rarest, with only about 500 cases chronicled in the medical literature since pathologists Jakob Erdheim and William Chester reported the first case in 1930. As yet, there is no cure.

Scientists believe runaway histiocytes are responsible. These specialized white blood cells that normally protect our immune system go haywire. Instead of fighting viruses and bacteria and then dying off, as is their job, the cells accumulate. They gather unpredictably in a variety of places: the long bones of the arms and legs, the tissue behind the eyes, the skin, the lungs, the kidneys, the adrenal or pituitary glands, the membrane around the heart, the abdominal cavity, the brain and sometimes other organs. Some patients experience bone involvement only. In others, as with Gary Brewer, the disease can attack multiple organs.

What is it?

Is it a cancer? An autoimmune disease? A metabolic disease?

“There are some metabolic aspects, but they are secondary,” says William Gahl, director of the Undiagnosed Diseases Program at NIH. “This is really a malignancy. The cells are not cancerous in the sense of being metastatic. They don’t move from place to place like they would in breast cancer. But they probably arise in the circulating bloodstream and then home in on certain places where they’re going to live, like the bone or the pituitary or the cerebellum.”

Gahl describes the resulting tumors as balls of tissue, sometimes an inch or two in size. They might encase the kidneys or arteries and stop blood flow. In the lungs, they can prevent the exchange of oxygen. “They grow at a very slow rate, but they’re in terrible places in our bodies,” he says.

It doesn’t help that Erdheim-Chester is notoriously difficult to diagnose and therefore, say researchers, most likely under- or misdiagnosed. Only when there’s a mass or lesion to study will pathologists look for identifying markers on cells — if they even suspect ECD. Then the hope is to stabilize patients and stall disease progression until a breakthrough is made.

Hoping for a breakthrough hasn’t been good enough for Kathy Brewer. “I couldn’t walk away and leave these people to go through the same hell that my husband had to go through,” she says, recalling the 50 binders filled with Gary’s medical records. These she had sent to one specialist after another, begging for help that never came. “It’s very hard not to feel like you failed your loved one when you’re the healthy one,” she says, her voice breaking. “I needed to understand: What did I do wrong? I had to start learning about the disease just to cope.”

And so she did. Brewer, who still lives in DeRidder, became friends online with two women whose husbands also had ECD. Together they created a weekly Internet chat group for patients and caregivers. The women stepped back to care for their spouses, but Brewer proceeded. She wanted the attention of researchers. She wanted a cure. “If I couldn’t do it for Gary, maybe I could do it for others,” she says.

Brewer has two engineering degrees and worked as a software developer and an environmental contractor before her marriage. She now works part time running a small consultancy. But with no money to start an organization and no medical background, where do you begin such a quest? In Brewer’s case, you start when a friend builds your website for free. You call yourself the ECD Global Alliance and eventually incorporate as a nonprofit organization. You plan vacations to France and Italy so you can meet with researchers who have published some of the few papers on ECD. You let them know you’re ready to help.

Then you receive some advice that makes all the difference. “Patients plus money equals research,” a doctor in Houston told her. That formula set her course: She needed to organize patients around the world. And she needed donations to fund grants. Only then would the researchers come to her.

That’s what she’s done. Today, 198 patients from 33 countries are registered on her site and living with the disease. An additional 46 are registered but deceased. The ECD Global Alliance has raised more than $500,000, mostly from patients or their families. That’s a drop in the bucket compared with groups that are focused on major diseases. Still, the alliance has awarded three $50,000 grants for the study of ECD and will donate more in the next few months, she says.

Going “door to door”

“When we started, I had to go literally door to door — it seemed — trying to find doctors and scientists who were interested in Erdheim-Chester,” Brewer says. This year, 10 researchers applied for grants, and most had to be turned away.

Brewer takes no salary. Supplies come from the dollar store. An accountant donates his time, as does the board of directors. There are two paid part-time employees.

Brewer’s devotion is paying off. She cobbled together a medical advisory board that includes experts from the Mayo Clinic, Johns Hopkins, the University of California at San Diego and other centers. In September, the alliance sponsored its second international medical symposium and patient and family gathering.

Perhaps most gratifying for Brewer is informing alliance members about the advances in research and treatment, including a study reporting that about half of Erdheim-Chester patients carry a genetic mutation called BRAF V600. That’s significant because many people with melanoma also carry it, and they respond to an enzyme inhibitor called vemurafenib. Although the alliance did not fund that study, Brewer was able to get the news out quickly to patients, who sought testing and treatment. “Doctors don’t have time to look up every article every day to see what’s been published,” Brewer says. “That was our role.” Now there is another drug in the arsenal along with certain immunotherapies and anti-cancer agents that can be used to contain the disease.

The alliance has also funded research at Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Then there was the event in 2010 that Brewer says was like winning the lottery. As she tells it, she was on the phone with someone at NIH, asking how she might get researchers interested in ECD. While on that call, an email popped into her inbox. It was from Juvianee Estrada-Veras, principal investigator of a new study at NIH. Would she and her organization be interested, the message read, in coordinating participants for a comprehensive study of Erdheim-Chester? “It’s one of those coincidences that just blows me away when I think about it,” Brewer says.

Fifty patients — there are openings for 100 in all — have enrolled in the study at NIH, where Estrada-Veras and his team hope to learn what causes ECD, how it develops and how to treat it. NIH pays all the patients’ medical costs and most U.S. travel expenses.

“When I bring someone here, the first thing I tell them is, ‘Thank you for coming; it’s going to be a really difficult week because of so much testing,'” says Estrada-Veras, who commented that he lost his mother, grandmother and aunt to rare cancers so he is sensitive to what they’re going through. “And then at the end of the week, the patients tell me, ‘For the first time, someone understands, someone listened to me.’ ”

According to Estrada-Veras, people with ECD are living longer because they are getting diagnosed earlier. He attributes some of that success to Brewer for networking with patients and doctors. Of his 50 patients, two have died of the disease. Of those remaining, about 40 percent have made it to the five-year mark and beyond. The rest were diagnosed more recently.

Since that first email, Estrada-Veras and Brewer have forged a friendship. “She’s like a mother,” he says, laughing. “She wants everything to be done for the patient the best way possible. She fights for them. She worries for them. She is their voice.”

He tells of other emails she sends him at 2 a.m. with questions about a patient from Singapore or Australia who has reached out to her. She wants to know if Estrada-Veras will talk to their doctors about referring them to the NIH study. “She’s always there, available at anytime,” he says. “Kathy is amazing. If ECD is ultra rare, then Kathy is ultra, ultra rare.”

Davidson writes about science and health. She is co-author of “Your Brain After Chemo: A Practical Guide to Lifting the Fog and Getting Back Your Focus.” Visit her website at www.IdelleDavidson.com.