Recent studies have linked high-calorie diets with increased cancer risk, while other research has shown an association between reduced caloric intake and lower risk of cancer. But tumor biology still hides complex mechanisms, as revealed in a new study, which found that switching from a low- to high-calorie diet can either encourage tumor growth or reduce it, depending on its stage of development.

The association between diet and cancer has long been of interest to scientists, as dietary habits represent a potentially modifiable risk factor. The general consensus in the research is that unhealthy diets may contribute to cancer development through both direct and indirect mechanisms, while healthy diets may prevent it.

For instance, several recent studies have found an association between dietary fat intake and breast cancer risk. Specifically, diets high in cholesterol and animal fats appear to increase women’s risk of developing breast cancer. Similarly, studies also suggest that high levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood may increase the risk of prostate cancer recurrence, while other research points to a link between dietary intake and cancers of the stomach, esophagus, colon, rectum, and pancreas.

Another line of research, conducted in animals, suggests that restricting caloric intake may slow or halt tumor growth. According to a 2013 review published in the journal Cancer and Metabolism, “calorie restriction is one of the most potent broadly acting dietary interventions for inducing weight loss and for inhibiting cancer in experimental [animal] models.” However, similar studies of human tumor growth have found inconsistent results.

In this latest study, researchers led by Dr. Roberto Coppari, a professor in the Department of Cell Physiology and Metabolism at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, set out to explore this issue further, with the goal of identifying the molecular mechanisms by which diet influences tumor growth.

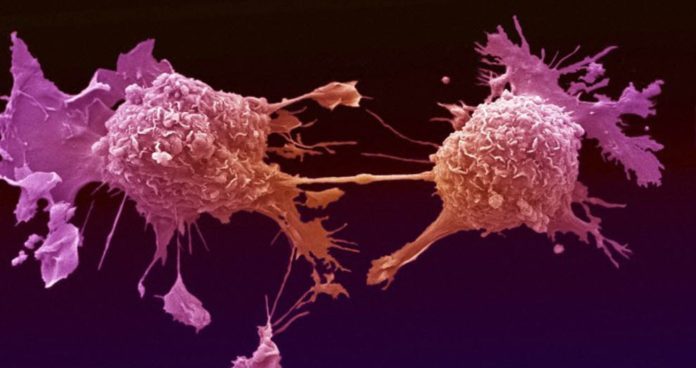

The researchers focused on tumors driven by mutations in the KRAS gene, which are often found in lung, pancreas and colon cancers. To investigate the impact of dietary factors, the team monitored tumor growth in the lungs in response to a change from a diet low in calories to a high-calorie diet.

High-calorie diet increases stress in endoplasmic reticulum of cells

The results of the study, published in the journal Cell Metabolism, revealed that conversion from a low- to high-calorie diet appeared to reduce tumor growth when the high-calorie diet was adopted before tumors started to grow. However, if the switch from a low- to high-calorie diet took place after tumor growth began, it boosted their growth further.

On further analysis, the team found that a change in diet triggered an increase in stress in the endoplasmic reticulum — an area in cells that regulates protein organization. A rise in stress in this area increases expression of chaperones, which are molecules that aid protein function.

The researchers note that high levels of stress in the endoplasmic reticulum can cause cells to die, making the cells unable to spur tumor growth. This may explain why changing to a high-calorie diet reduced tumor growth.

The team says changing to a high-calorie diet after tumor growth started, however, may fuel further growth because the tumor cells have already adapted to an increase in endoplasmic reticulum stress; more stress encourages further tumor cell proliferation.

The fact these effects are dependent on the stage at which dietary change takes place indicates that the effects are not due to the diet per se, but to the metabolic changes they engender, the authors say.

“Our study does not show that, by eating junk food, people would be protected from lung cancer,” explains study co-author Dr. Giorgio Ramadori. “But the high-calorie diet helped us discover a very specific molecular mechanism required for lung tumor cells to proliferate that could pave the way for new therapeutic approaches.”

Blocking FKBP10 could impair cancer cell growth while avoiding healthy cells

By analyzing the RNA molecules of lung tumors from both low- and high-calorie diet groups, the team found that switching to a high-calorie diet significantly reduced expression of a chaperone protein called FKBP10, which was only found in lung cancer cells.

The researchers explain that FKBP10 is not usually found in healthy adults, but it can be found in the developing embryo and young infants; it deals with increased endoplasmic reticulum stress by expressing chaperones.

After human development is complete, however, endoplasmic reticulum stress reduces, meaning chaperone expression is no longer required. The fact FKBP10 was found in lung cancer cells means it is likely there to deal with a rise in endoplasmic reticulum stress once again.

Dr. Coppari and his team note that cancer treatment usually leads to death of both cancer cells and healthy cells. But they say that blocking FKBP10 could impair cancer cell proliferation without killing healthy cells, offering a potential new strategy to treat cancer patients. Dr. Coppari explains further:

“In this study we show that knockdown of FKBP10 leads to reduced cancer growth. Human lung cancer cells express FKBP10 while the nearby healthy lung tissue does not; this is very interesting and appealing to eventually translate these findings to the clinical arena.

Hence, if we manage to identify the right inhibitor, we may open the door to new therapeutic strategies that will be able to hinder cancer cells’ proliferation without damaging the healthy cells. The inhibition of this protein is predicted to have minimal side effects as it is not expressed in healthy tissues, at least in adulthood.”

The authors say that if preclinical results confirm these findings, then clinical trials testing the theory could begin within a few years.