As people in developing nations relocate from rural areas to cities, the increased stress is affecting their hormone levels and making them more susceptible to diabetes and other metabolic disorders, reveals a new study published in the Endocrine Society’s Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

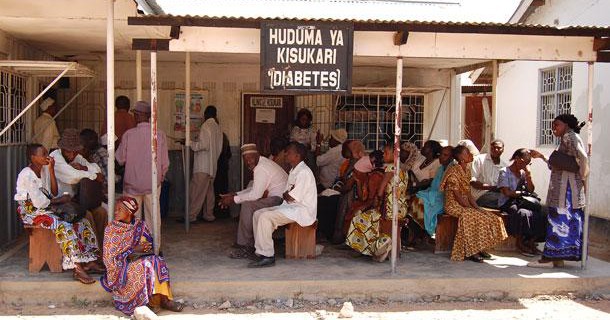

About 387 million people worldwide have diabetes, and 77 percent of them live in low- and middle-income countries, according to the International Diabetes Federation. In the Middle East and North Africa, one in 10 adults has diabetes.

One factor that can raise a person’s risk of developing diabetes and other metabolic problems is chronic exposure to the stress hormone cortisol. Cortisol can counteract insulin, the hormone that regulates blood sugar, and slow the body’s production of it.

“Our findings indicate that people who leave a rural lifestyle for an urban environment are exposed to high levels of stress and tend to have higher levels of the hormone cortisol,” said study author Dr. Peter Herbert Kann, MD, PhD, MA of Philipp’s University in Marburg, Germany. “This stress is likely contributing to the rising rates of diabetes we see in developing nations.”

To test the theory, researchers examined people from one ethnic group — the Ovahimba people of Namibia in southwestern Africa. Namibia is the second least-densely populated country in the world, with 38.6 percent of residents living in urban environments.

In the prospective, cross-sectional, diagnostic study, the researchers measured cortisol, blood sugar and cholesterol levels in 60 Ovahimba people living in Opuwo, the regional capital. Opuwo has a population of around 21,000. The researchers then conducted the same tests on 63 Ovahimba people living at least 50 kilometers from the nearest town or village.

Among the urban residents, 28 percent of the people had diabetes or other glucose metabolism disorders, the study found. The prevalence was less than half that for rural residents (12 percent). The urban dwellers also had significantly higher cortisol levels than their rural counterparts.

Past research has shown that the process of urbanization — migration from rural areas to towns and cities and the expansion of urban areas into the periphery — is linked to changes in diet and behavior, which have resulted in rising rates of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic conditions.

In line with those findings, the results of this latest study revealed that city residents exercised less and ate more fast food and desserts than the rural residents. However, lifestyle changes aren’t the only factor at work, said Dr. Kann. He explained that the difference in cortisol levels between the two groups indicates that the hormone is a key part of the equation.

“This is the first prospective study to systematically show the body’s regulation of the hormone cortisol plays a part in the metabolic changes brought on by the shift to an urban lifestyle,” said Dr. Kann. “The results suggest sociocultural instability caused by urbanization contributes to an increased risk of developing diabetes or another metabolic disorder.”

In the past 50 years there has been a twofold increase in the percentage of the world’s population living in urban areas. Approximately 25 years ago, less than one-third of the world resided in urban areas. And yet in less than 25 years it is anticipated that almost two-thirds of the world’s population will be living in cities. More important, the percentage of the world population living in urban areas will increase less in developed regions (from 54.9 to 83.5) than in less developed regions, where it will increase from 17.8 to 56.2. Therefore, the future burden of urbanization will fall largely on developing countries.

Although the study didn’t address the underlying causes of the observed increase in cortisol levels among urban residents, past research indicates that the shift to urban living is a process fraught with stressors. Along with increased rates of poverty and unemployment, urbanization also brings with it challenges such as higher levels of pollution, frequent exposure to violence, and reduced social support.

A 2009 article in the New England Journal of Medicine warned that urbanization is a “health hazard for certain vulnerable populations,” and that the accompanying demographic shift “threatens to create a humanitarian disaster.” What’s more, experts say that over the coming decades, the effects of climate change and urbanization will interact, with unpredictable outcomes. According to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, “urbanization and climate change may work synergistically to increase disease burdens.”