Health care is ripe for innovation, especially in the realms of health care services and information technology (IT). This situation is one of the main reasons there has been such impressive growth in digital health funding over the past few years. However, much of that investment and many new companies in the health care delivery [1] space are not truly adding value or addressing fundamental problems.

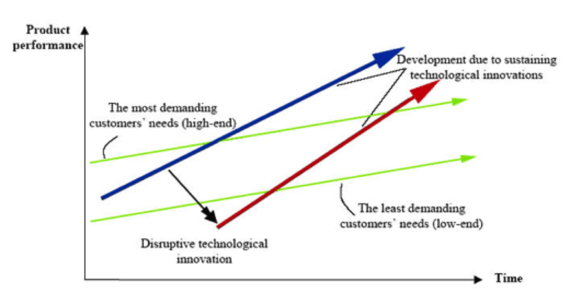

Having worked in health care from both the business and clinical perspectives, I’ve heard countless companies — big and small — talk about revolutionizing health care. Many of the newer companies even use the word “disrupt,” borrowing from the concept of disruption made famous by author and Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen. Let’s clear up what disruption actually entails. The below graphic highlights the key points.

In disruption, an innovation starts by providing a meaningful but lower value service than what currently exists, thereby creating a new market of customers who were previously not served. A recent example of disruptive technology would include the iPad as compared to traditional laptops. As disruptive innovations evolve, they climb the performance value chain. Ultimately, they can become the preferred service/technology and displace the incumbent — or at the very least take significant market share.

In New York and several other major cities, Uber has disrupted the taxi industry by providing a more convenient service often at a lower price than standard taxis, recent legal action and surge pricing notwithstanding. Recently, I became aware of Pager, a New York-based company started by one of Uber’s co-founders, Oscar Salazar, as well as a similar company in South Florida named Medicast. Both have been profiled on CNN and are trying to bring back the storied concept of the doctor house call — albeit for the concierge market. In late October, Uber began a partnership with Pager for its own UberHealth initiative.

As a practicing physician with several years of clinical experience, I can say that there are only a small number of illnesses I can treat confidently without referring a patient for basic labs, imaging, or monitoring. House calls traditionally had the most benefit in rural/underserved locations where access to health care is limited — not in major cities with ample resources. Furthermore, in a major metro area like NYC, there is no shortage of urgent care centers and retail clinics with late hours that offer a wider array of services for the $199 price tag of a house call. Although it may be possible to generate revenue, serving a concierge population with a lower value service is hardly disruptive. And in the broader context of health care, it does not address a major problem, lower costs in the long run, or improve societal health. So those issues leave me asking, what benefit does the premium option of a house call have beyond convenience? How does it truly advance health care or fulfill an unmet need?

The aforementioned questions got me thinking about the broader topic of recent health care innovation. When we think about U.S. health care economics, it’s important for people to realize that 1 percent of the population accounts for more than 20 percent of overall health care spend (and an average annual mean expenditure greater than $90K per patient), with the top 5 percent of health care users representing almost 50% of health care expenditures [2]. Given that current health care spending is approximately $2.9T (and more than 17 percent of the nation’s GDP), 5 percent of the population currently requires almost $1.5T of health care resources. High intensity users of health care are those with chronic illnesses, and often elderly. Per the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), they likely have some combination of heart disease, trauma-related disorders, cancer, mental illness, and asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). In addition, these patients receive care in the inpatient setting far more frequently than the general population.

To improve health care dramatically and bend the cost curve, entrepreneurs and innovators need to help create better methods to treat the chronically ill and utilize health care resources more efficiently. Further upstream, they also need to identify those most at risk and help them maintain health. In a recent Wired article by J.C. Herz titled “Wearables Are Totally Failing the People Who Need Them Most,” Herz discusses how the wearables [3] market is insufficiently focused on the elderly and chronically ill who could benefit most from such medical technology. One particular line from the article was rather scathing:

From Silicon Valley and San Francisco to Austin and MIT, young, healthy, highly educated, mostly male entrepreneurs are developing marginally useful apps and gadgets for people just like themselves.

Clearly there are some health care startups that will meaningfully improve health care. But there is justifiable concern that too many are focused on the wrong patients and wrong problems using technology with limited applicability.

At around the same time, I read about an Indian company developing a portable diagnostics tool, the Swasthya Slate (which translates to “Health Tablet”). The Slate is capable of running more than 30 different tests with a degree of accuracy comparable to medical lab equipment. In time, its developers are hoping to be able to produce the tool for $150 per unit while continuing to expand the diagnostic tests it can run. The product’s current target market is rural Indian patients with limited access to health care. However, the Slate has potential broad applicability and defines disruption far more than any exercise wearable or house call application for the urban wealthy.

Similarly, the concept of house calls does have validity in improving health care and ultimately lowering costs, but in a different model than Pager, Medicast, or UberHealth. Based on his work as a primary care physician in Camden, New Jersey, Dr. Jeffrey Brenner pioneered the concept of “hot spotting.” He brought together teams of social workers, nurses, community health workers, and medical professionals who regularly made house calls to high intensity patients, or “super utilizers,” that accounted for a disproportionate share of Camden’s health care costs. Brenner realized that such patients needed to be engaged differently than traditional patients. His model was so successful in lowering hospital visits for the most challenging patients that it has led to more than 50 similar operations throughout the country. Brenner himself was honored with a MacArthur “genius” grant in 2013 to continue his work. In a recent Scientific American interview, Brenner explained that he is currently trying to quantify exact cost savings using his approach and demonstrate the scalability of hot spotting throughout the country.

Health care is at an interesting juncture. Current practices in health care are fragmented, cumbersome, and often archaic. Society and the medical community realize that there has to be more effective and efficient ways to deliver care. In turn, there has been significant entrepreneurial and investment activity in health care delivery. Rather than simply looking at health care as a huge market in which to make money though, I hope entrepreneurs and investors will pursue and support innovation that addresses fundamental, unmet needs.

I firmly believe it is possible to be profitable and meaningfully improve health care for everyone — not just premium markets. However, it will take a nuanced understanding of current health care operations and care gaps to accomplish that goal. UberHealth may not be the right platform, but I look forward to hearing about the next Swasthya Slate or thoughtful coordinated care platform — and ultimately a world where health care delivery is far more advanced. Patients and the medical community alike are sorely asking for it.

References:

[1] For the purposes of this article, health care delivery refers to the combined realms of health care services and IT.

[2] http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st359/stat359.pdf

[3] Wearables are non-implanted sensors that track, measure, and transmit information about a patient’s activity or physical state. Current consumer examples include the Fitbit and Nike Fuelband.