In addition to incurring serious dental problems, memory loss and other physical and mental issues, methamphetamine users are three times more at risk for getting Parkinson’s disease than non-illicit drug users, reveals new research from the University of Utah and Intermountain Healthcare.

The study, published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, also showed that the link between methamphetamine use and Parkinson’s disease was stronger among women than men, although the reason for this apparent gender difference is unknown.

“Typically, fewer females use meth than males do,” says Dr. Glen R. Hanson, D.D.S., Ph.D., a nationally recognized expert in drug addiction, professor and interim dean of the University of Utah School of Dentistry and professor of pharmacology and toxicology, the study’s senior author. “Even though women are less likely to use it, there appears to be a gender bias toward women in the association between meth use and Parkinson’s.”

Methamphetamine is a central nervous system stimulant drug that is similar in structure to amphetamine and carries a high potential for abuse. Its popularity has waxed and waned over the years, but its use seems to be increasing in many parts of the United States and in several population subgroups. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), approximately 13 million Americans over the age of 12 have used methamphetamine and about 500,000 are regular users. Nationwide, the percentage of drug treatment admissions due to methamphetamine and amphetamine abuse tripled from 3 percent in 1996 to 9 percent in 2006. Some states have much higher percentages, such as Hawaii, where 48.2 percent of the people seeking help for drug or alcohol abuse in 2007 were methamphetamine users.

Physical and psychological effects

Like most addictive drugs, the initial effects of methamphetamine — namely, increased energy, reduced appetite, and heightened sexual arousal — are pleasurable to the user. However, tolerance to methamphetamine’s pleasurable effects develops when it is taken repeatedly. Users often need to take higher doses of the drug, take it more frequently, or change how they take it in an effort to get the desired effect. The discontinued use of methamphetamine by heavy users will create withdrawal symptoms, including severe depression, lethargy, anxiety and fearfulness.

Prolonged use of methamphetamine can also cause sleeplessness, loss of appetite, increased blood pressure, paranoia, psychosis, aggression, disordered thinking, extreme mood swings and sometimes hallucinations. Many users become physically rundown, which leaves them susceptible to illness, and certain routes of drug use — particularly intravenous — can lead to increased transmission of infectious diseases, such as hepatitis and HIV/AIDS.

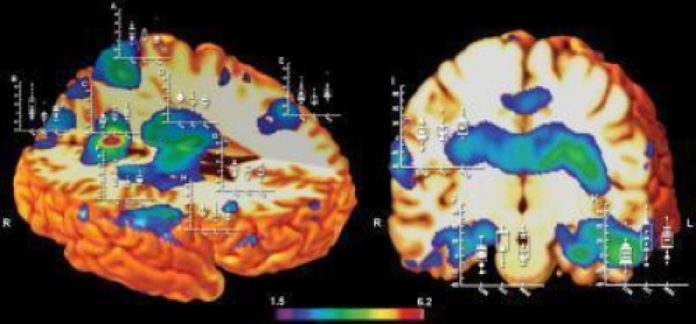

More recently, scientists have also discovered evidence of significant changes in the brain caused by abuse of methamphetamine. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated alterations in the activity of the dopamine system that are associated with reduced motor speed and impaired verbal learning. Studies in chronic methamphetamine abusers have also revealed severe structural and functional changes in areas of the brain associated with emotion and memory, which may account for many of the emotional and cognitive problems observed in chronic methamphetamine abusers.

Some of the neurobiological effects of chronic methamphetamine abuse appear to be at least partially reversible. For instance, studies indicate that performance on motor and verbal memory tests improves after 14 months of abstinence from the drug. However, function in other brain regions has been found to remain impaired even after nearly a year-and-a-half of abstinence, indicating that some methamphetamine-induced changes may be very long lasting.

Largest study of its kind

This latest study looked at more than 40,000 records in the Utah Population Database (UPDB), a unique compilation of genealogical, medical, and government-provided information on Utah families that is managed by the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah. Records from University of Utah Health Care and Intermountain Healthcare also provided unidentified patient data that was essential for getting a statewide perspective on the research.

The findings confirm an earlier study that looked at nearly 250,000 California hospital discharge records and found a similar risk for Parkinson’s among meth users. That study, however, did not report risks based on gender and looked only at records of hospital inpatients. The new analysis included both Utah inpatient and outpatient clinic records, capturing a wider segment of the population.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive movement disorder, with onset typically at age 60 or older, that affects nerve cells in the brain. Its symptoms include tremor, or shaking, often starting in a hand or fingers; slowed movement, such as walking; rigid muscles; loss of automatic movements-blinking or smiling, for example-and speech changes. There is no cure for Parkinson’s, but medications and surgery can alleviate symptoms. It is estimated that 4 million to 6 million people worldwide have the condition.

Dr. Hanson’s team examined medical records, dating from 1996 through 2011, and separated them into three groups: those of nearly 5,000 people whose health records indicated they had used meth (including amphetamines), more than 1,800 records indicating cocaine use, and records of a control group of more than 34,000 people selected at random whose health and other records showed no use of illicit drugs. The control group was matched to the meth and cocaine users according to age and sex. The researchers made sure that the group of meth users did not have a medical history of taking other illicit drugs or abusing alcohol, which might have influenced the risk for Parkinson’s.

Higher risk for women

The results showed that cocaine users, who provided a non-meth illicit drug comparison, were not at increased risk for Parkinson’s. “We feel comfortable that it’s just the meth causing the risk for Parkinson’s, and not other drugs or a combination of meth and other drugs,” Hanson says.

In addition to finding that meth users have three times the risk for getting Parkinson’s disease as non-users, the researchers also observed that female meth users were nearly five times more likely than women who did not use drugs to develop Parkinson’s.

“Normally, women develop Parkinson’s less often than men,” says lead author Dr. Karen Curtin, Ph.D., assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah and associate director of the UPDB. The reason female meth users are more at risk for Parkinson’s is not clear, say the authors. Symptoms of the disease appeared in both female and male meth users in their 50s or later, indicating that the effects of meth may manifest years after initial use. “Oftentimes, we think about what drugs do in the short term, but we don’t tend to give much thought to long-term consequences,” say Dr. Curtin.

Meth has become in some ways the drug of choice in the West, where it’s used more commonly than in other parts of the country. In some areas, the authors note, the trend toward meth use is particularly pronounced in women their late 20s and older who start taking the drug because of pressure from a partner or spouse. “Female users … may also get involved with meth because it’s seen as a relatively cheap and effective way to lose weight and have more energy,” adds Dr. Curtin. Whatever the reason, she says, “If meth addiction leads to sharply increased incidence of Parkinson’s disease in women, we should all be concerned.”