People might take selfies someday to detect a deadly yet treatable medical condition, according to an award-winning team of medical inventors.

Jarrel C. Seah and Jennifer S. Tang — two medical students at Melbourne’s Monash University — came up with the idea when doing medical training in rural areas of Australia.

“Seeing people travel for hours to access medical care and seeing areas where there just wasn’t the equipment to do a blood test sparked the team to think of a simple and efficient way to screen for anaemia,” Seah says.

Anaemia is a condition where the body doesn’t have enough red blood cells that work properly, according to the World Health Organization. This condition affects 1.6 billion people worldwide and is more common in young children and pregnant women. Severe anaemia can stunt a child’s growth and learning. Untreated anaemia can increase the risk of dying, especially in pregnant women. Anaemia can result in lost wages by reducing work productivity.

More than half of the cases of anaemia are caused by low iron levels and can be treated with iron supplements, according to global health experts. But easy-to-use, reliable, and cheap methods to detect anaemia and monitor the effects of treatment are still needed.

“Eyenaemia is a simple, non-invasive and easily accessible screening tool for anaemia made for use by everyday people,” says Tang, who taught herself how to program in medical school. “Screening for anaemia is as simple as taking a selfie.”

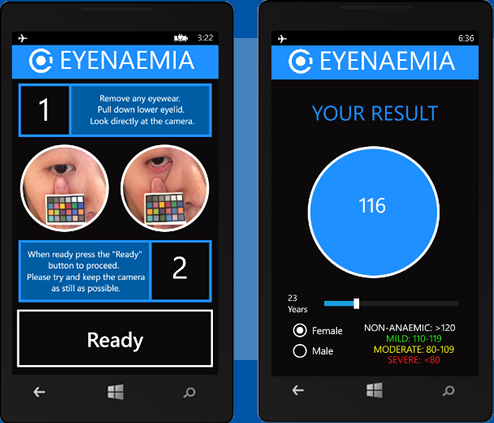

She outlines the steps to using Eyenaemia:

1. Tape a color calibration chart to your finger. This chart allows the app to adjust for different lighting conditions.

2. Pull down your lower eyelid to expose the inner surface, which has a rich supply of blood vessels.

3. Take a photo of your eyelid and finger.

Eyenaemia analyzes the color of the inside of your lower eyelid and estimates how much hemoglobin you have, the inventors say. A lighter color signals a lower hemoglobin level. Hemoglobin is a protein found in red blood cells and is measured in lab tests to detect anaemia. The app calculates your anaemia risk based on your hemoglobin level, age, and sex.

The beauty of this solution is that it provides an objective analysis compared to a doctor’s assessment, Tang says, citing studies showing that doctors who check the color of the inside of a patient’s eyelid have anaemia detection rates ranging from 25 percent to 84 percent, she says.

Eyenaemia works with a digital camera or any device that has a camera, Tang says, explaining that this app is compatible with flip phones, smartphones, tablets, laptops, and computers.

“Because it’s non-invasive, it’s particularly suited for young children,” Seah says, explaining that the needles used for blood tests can be traumatic for kids.

He says that Eyenaemia could be useful in allowing doctors to remotely check whether people are getting better with treatment and this would allow patients — especially those who have to travel long distances — to avoid coming in for a follow-up visit and blood testing.

This invention has garnered many awards, including first place for Microsoft’s 2014 Imagine Cup, a global student technology competition.

“We didn’t expect to win,” Tang says.

The team only started building the app in February of this year and were selected as the Imagine Cup World Champions by August, she says.

“We had a meeting with Bill Gates,” Tang says. “[He] said our solution had the potential to be a ‘real life-saver in the developing world.'”

More research is needed before this app can be used for screening and monitoring this disease worldwide, says one leading mobile health expert, who is not involved with Eyenaemia.

“Certainly an easy and non-invasive test for anaemia would be useful,” says Dr. Joel D. Selanikio, a pediatrician and assistant professor at Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., and CEO of Magpi, a free mobile data collection system.

Doctors may be unsure about using this app until studies show that Eyenaemia’s hemoglobin values closely match lab blood test results, he says.

Seah and Tang have already begun a multi-center clinical trial with several hundred enrolled subjects to compare Eyenaemia’s results to lab blood tests.

A microscope slide of red blood cells showing iron-deficiency anaemia. (Image credit: Robert J. Galindo)

Tang was invited to speak in New York City at the United Nations Women’s Entrepreneurship Day, a humanitarian campaign launched to create a better world for girls and women.

“We searched for extraordinary women social entrepreneurs focused on solving the world’s problems,” says Wendy Diamond, an American humanitarian, social activist, and founder of Women’s Entrepreneurship Day.

Social innovators who make the world a better place should be our heroes, she adds.

“Globally, girls and women are disproportionately affected by anaemia and they stand to gain the most with timely detection and treatment,” says Kunal Sood, a global health researcher and Chairman of the Women’s Entrepreneurship Day Fellows Program.

“Eyenaemia’s revolutionary approach to detecting anaemia could positively impact the lives of millions of girls and women around the globe.”

Disclosure(s): Dr. Julielynn Wong is a United Nations Women’s Entrepreneurship Day Distinguished Fellow.