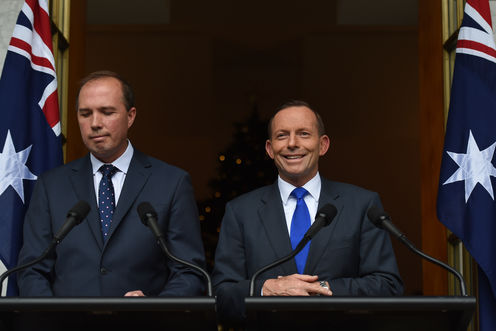

In the government’s latest “scraping away the barnacles” of unpopular and blocked policies, prime minister Tony Abbott and health minister Peter Dutton have announced they’re abandoning the plan to have doctors charge a $7 co-payment for consultations. Facing a massive backlash from both the medical profession and the public, the budget measure was facing almost certain defeat in the Senate.

Abbott and Dutton have outlined an “optional” co-payment, which makes doctors responsible for charging it. It reduces the rebate doctors receive for treating patients by $5 and freezes it until July 2018. General practitioners can pass on this cut by charging patients who do not have health-care (concession) cards and are aged over 16.

Both versions of the co-payment policy are just the latest stoush in long battle over bulk billing, which lies at the centre of Medicare, and the scope of universal health coverage in Australia. Bulk billing – where general practitioners bill Medicare directly without charging patients upfront fees – has, in fact, played an unusually prominent role in Australian health policy conflicts.

“Free” access to the gatekeeper role of general practice enraged conservative critics of Medicare from the start. At the same time, defenders of Medicare treat it as a line in the sand; any attack on bulk billing is equated with an assault on Australia’s public health system.

A doomed policy

The original policy, announced in the May budget, was complicated and poorly explained. Here’s a brief summary of what it entailed.

From July 1, 2015, previously bulk-billed patients would pay $7 towards the cost of standard medical consultations and out-of-hospital pathology and imaging services. Some patients – including children under 16 and health care card holders (low-income earners and pensioners) – would be exempt from the co-payment after their first ten visits in a calender year.

In effect, the structure of bulk billing would remain intact. Doctors could still bill Medicare directly, but their patients would have to pay the $7 co-payment. If they charged the full amount, general practitioners would receive an additional $2 in the rebate from the government. The other $5 raised by the co-payment would go into a Medical Research Future Fund, which would start disbursing the interest it garnered after it had collected $20 billion.

The policy was attacked from all sides. Defenders of Medicare saw it as another round in the Coalition’s attempts to undermine universal coverage. And the Australian Medical Association (AMA) – long ambivalent about bulk billing – criticised the complexity of the arrangements, and demanded the exclusion of vulnerable people.

Australia already has one of the largest and most complex set of co-payments for medical services in the developed world. Proponents of a “price signal” for health seemed ignorant of the bewildering array of price signals already faced by anyone with a serious and continuing illness.

And no one, including the government, has proffered any modelling to justify the claim that a co-payment would make the system more efficient, rather than just add to the existing obstacle course.

Even the medical research community seemed either bemused and embarrassed by the linking of the co-payment to a new Medical Research Future Fund. This move, which seemed calculated to divide medical groups, confused the government’s message that the measure was part of its program of “budget repair”.

It was hard to find anyone with a good word to say about the policy. And its doom in the Senate seemed certain.

An official report released in September showing federal government spending on health has been declining – and will fall further with cuts in transfers to state hospital systems – made the justification for the change look even more fragile.

Back to the future

So how is the new policy likely to be received? The AMA has always been comfortable with co-payments, but not with cuts in the rebate. Its national president, Brian Owler, has described the announcement as a “mixed bag”.

The “optional” co-payment ends the administrative nightmare of charging concessional patients for just their first ten visits. It also removes proposed co-payments on pathology and other diagnostic tests.

But it remains a cost shift from the government to individuals, with doctors squeezed in the middle. It may have severe effects on the viability of practices in poorer areas where general practitioners may not feel they have the option of passing on the rebate cut.

The odd thing about this saga is that we have been here before. In 1996, the Howard government froze GP rebates. Over the next three years, this squeezed doctors’ incomes, which fell almost 20% in relation to average weekly earnings.

One result was a slow abandonment of bulk billing, not out of ideological hostility, but to maintain practice incomes. Bulk billing had been at a high of 80.6% of services in 1996, but fell to 68.5% in 2003-04. The shift was even greater in areas with fewer general practitioners, especially in remote and rural places.

A political backlash developed; the government faced hostile criticism from doctors, the AMA, and patients. The response was “A Fairer Medicare”, launched in April 2003. It brought in new subsidies for bulk billing in rural and remote areas and incentives for bulk billing health-care card holders.

Opponents argued it was nothing of the sort; health care card holders were only a minority of those in need, and the policy continued to push general practitioners out of bulk billing. The Senate, controlled by Labor and the Greens, blocked “A Fairer Medicare”.

With a federal election looming, John Howard appointed Tony Abbott as the new Minister for Health, gave him an open cheque book and a mandate to remove bulk billing as an electoral issue.

“Medicare Plus” restored the level of all general practitioner rebates, with extra incentives (which remain in place) to bulk bill children and pensioners. The restoration led to a return of bulk billing. And by 2006, it was back to 78% of services. Tony Abbott used these bulk billing figures to proclaim himself “Medicare’s greatest friend”.

Will the latest changes meet the fate of “A Fairer Medicare”? The Abbott government’s changes will be introduced by regulation, avoiding an immediate Parliamentary vote. But they can be reversed by a Senate vote when Parliament reconvenes in early 2015.

The exclusion of some low-income groups and children may make the new policy more palatable to the cross-benchers who will decide its fate. But the freeze of the rebate and long-term pressure to abandon bulk billing mean neither general practitioners nor many of their patients will be appeased.

Jim Gillespie receives research funding from NHMRC and WentWest/ Western Sydney Partners in Recovery.