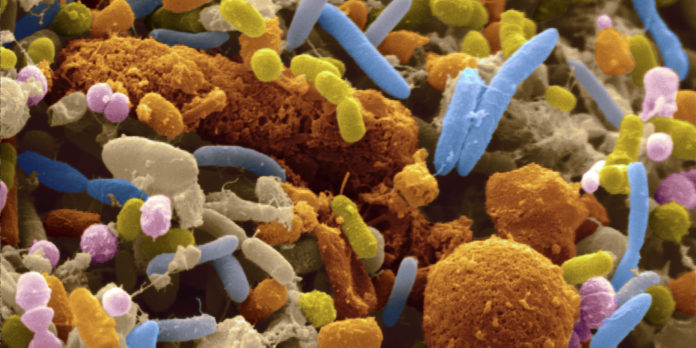

Promoting healthy gut microbiota, the bacteria that live in the intestine, can help treat or prevent metabolic syndrome, according to a new study published in the December issue of the journal Gastroenterology.

Metabolic syndrome is a combination of risk factors that increase risk for heart disease, diabetes and stroke. When a person has three of the following risk factors, they are classified as having metabolic syndrome:

- A large waistline

- High levels of triglyceride (a type of fat found in the blood)

- Low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level

- High fasting blood sugar.

People with metabolic syndrome are twice as likely to develop heart disease and five times as likely to develop diabetes as the general population, according to the National Institutes of Health.

The American Heart Association reports that more than a third — 34 percent — of American adults have metabolic syndrome. As the incidence of obesity continues to rise, metabolic syndrome is becoming more common, prompting scientists to investigate possible causes.

The team behind this latest study, from Georgia State University (Atlanta) and Cornell University (Ithaca, NY), had found in previous research that altered gut microbiota (intestinal bacteria) plays a role in metabolic syndrome.

In addition to promoting the inflammation that leads to metabolic syndrome, altered gut microbiota promotes chronic inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

New findings explain mechanisms identified in previous research

According to study author Dr. Andrew Gewirtz, a professor in the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State, the new research has filled in the details about how these mechanisms work.

“It’s the loss of TLR5 on the epithelium,” he explains, “the cells that line the surface of the intestine and their ability to quickly respond to bacteria. That ability goes away and results in a more aggressive bacterial population that gets closer in and produces substances that drive inflammation.”

In a model of mouse siblings, the researchers demonstrated that the altered gut microbiota that promotes inflammation is more aggressive than other bacteria in infiltrating the epithelium.

Some of the mice in the study were missing the TLR5 gene, which the researchers found caused alterations in the inflammation-driving bacteria that promoted metabolic syndrome.

“These results suggest that developing a means to promote a more healthy microbiota can treat or prevent metabolic disease,” says co-author Dr. Ruth Ley, of the departments of Microbiology and Molecular Biology at Cornell.

“They confirm the concept that altered microbiota can promote low-grade inflammation and metabolic syndrome and advance the underlying mechanism. We showed that the altered bacterial population is more aggressive in infiltrating the host and producing substances, namely flagellin and lipopolysaccharide, that further promote inflammation,” adds Dr. Ley.

These findings add to a growing line of research linking gut microbiota to obesity and related conditions. According to one recent study, the composition of bacteria in the gut is a major determinant of adult body weight and, as such, may be a modifiable risk factor for obesity. Other recent research suggests that certain probiotics may even play a role in preventing obesity.