Poor teens who feel positively about their community may be protected from some of the damaging effects of poverty on mental health, according to new research on teenagers living in impoverished neighborhoods around the world.

Researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health surveyed 2,400 low-income adolescents (ages 15 to 19) in five cities: Baltimore, Maryland; New Delhi, India; Ibadan, Nigeria; Johannesburg, South Africa; and Shanghai, China. Their findings were published in five reports that made up a special supplement to the December 2014 issue of the Journal of Adolescent Health.

Researchers asked the young people how they felt about their physical environment and whether they felt they had positive adult role models to offer social support. Teens were also asked about health issues they faced, including mental health problems like depression. They reported issues like teen pregnancy, violence, depression, post-traumatic stress, HIV and suicide attempts.

While the teens came from around the world, the researchers found that the relative wealth of their home countries was not correlated with better mental health outcomes. Rather, a combination of having positive adult role models and a favorable perception of their neighborhood made a teen more likely to report better mental health.

In Baltimore, for example, teens did not feel safe, even in their homes. They also reported seeing violence in their neighborhood and felt they lacked positive adult role models. Baltimore respondents reported high levels of depressive symptoms, including post-traumatic stress and thoughts of suicide.

In comparison, despite rampant poverty in India, the adolescents in the study from New Delhi felt safe in their homes and weren’t exposed to much violence. These teens reported lower levels of depression than the other teens surveyed.

“If there is nobody giving you positive support, and then you look outside and there are rats and garbage — it’s those two layers just reinforcing each other,” said Kristin Mmari, an assistant professor in the Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School and a co-author of the study. “Does anybody care about me? They look out their windows. They are afraid. They don’t feel safe. It’s that combination of factors that is affecting them.”

“I think it’s not so much the country income level, it’s really the environment. What neighborhood are you living in? How do you perceive that neighborhood?” Mmari said.

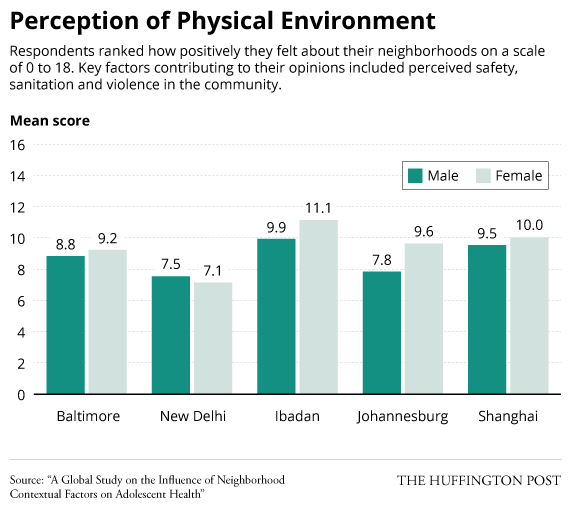

In the graph below, respondents ranked how they felt about their community’s physical environment, considering factors like inadequate sanitation, overcrowded buildings and violence levels. Adolescents from Shanghai and Ibadan gave their communities more favorable ratings, while adolescents from New Delhi and Johannesburg gave their neighborhoods low rankings.

According to a female respondent from Johannesburg:

The thing is that where we stay, you will hear a person screaming from being beaten up in the middle of the night and there is also break-ins.

A male respondent from Baltimore reported similar violence:

There ain’t nowhere to be safe, tell you the truth. All I’m saying is it’s not even safe to even walk around by yourself at a certain time, even though you don’t have a curfew. It’s not. Three years I got banked [beaten] so many times it doesn’t make no damn sense.

The graph below maps social cohesion, or how connected each individual felt to his or her community. Adolescents in Baltimore and Johannesburg ranked their level of social cohesion lower than adolescents in the other cities, listing a lack of community involvement and dearth of positive adult role models in their lives as reasons they didn’t feel connected.

According to a female respondent from Baltimore:

A lot of the parents are out here on drugs. So, the kids are being raised by themselves.

A Johannesburg respondent reported a similar lack of adult guidance:

We find that most of them are coming from single headed families where there is only one parent and the other party is not there. So they are very vulnerable.

Researchers found that a combination of these two key factors — physical environment and social environment — could be affecting the mental health of the adolescent respondents. In the graph below, respondents from Johannesburg and female respondents from Baltimore reported experiencing high levels of depressive symptoms. According to Mmari, in neighborhoods where both physical environment and social environments are considered poor, negative health outcomes become much more prevalent.

“[Baltimore and Johannesburg] had the highest percentage of adolescents growing up without two parents, and in the qualitative findings, they talked about not having a whole lot of positive adults in their lives. In addition, adolescents in those two sites were more likely to rate their physical environment as very poor,” Mmari said. “The interaction that these two domains have with each other is really important.”

These findings, however, only represent the youth experience in one neighborhood per city, and can’t necessarily be extrapolated to represent the experience of poor young people on a city-wide level. Mmari said she this is one of the limitations of the study. “What I would love to do is have more neighborhoods in each of these cities,” she said. “How do these neighborhoods vary? In turn, how do their health outcomes vary, within the same city?”