National Institutes of Health researchers reported on Wednesday that a possible vaccine for the Ebola virus appears to be safe in early testing and that a clinical study in West Africa can go ahead as planned late this year or in early 2015.

A look at the first group of people injected with the vaccine, which has been shown to protect monkeys from Ebola, shows no dangerous side effects. And it seems to be producing an immune response that would be expected to protect them from infection. The scientists reported the results of the Phase I testing in the New England Journal of Medicine on Wednesday.

“Based on these positive results from the first human trial of this candidate vaccine, we are continuing our accelerated plan for larger trials to determine if the vaccine is efficacious in preventing Ebola infection,” said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., head of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which helped develop and test the vaccine.

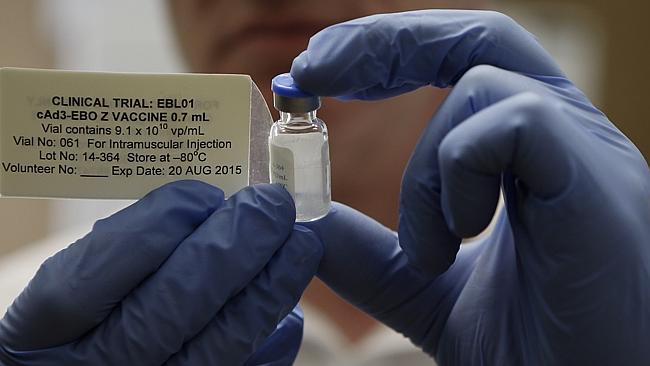

The vaccine, made by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) in partnership with British pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, uses a common cold virus called an adenovirus that normally infects chimpanzees. It doesn’t cause any symptoms in people. It’s genetically engineered with a small piece of Ebola virus and, in theory, should prompt the immune system to recognize and attack the Sudan and Zaire strains of the Ebola virus – the latter the one behind the current deadly outbreak in West Africa.

Preliminary findings indicate a possible protective effect

There’s no ethical way to vaccinate people and then expose them to Ebola on purpose, of course, so the trial was designed to see if the vaccine is safe and if the immune system responds in a way that would be expected to protect them. The trials were conducted at the NIH in Bethesda, Md., with 20 healthy participants who received doses of the vaccine. The vaccine was given in different doses to two groups among the 20 volunteers.

The volunteers given a higher dosage developed far more immune response than did the other group, a step that may help researchers home in on the proper dose in the larger trials in West Africa. However, those findings would be considered very preliminary and not evidence that the vaccine is working.

Clinical trials of the vaccine are continuing; the plan is for the candidate NIH/Glaxo vaccine to be tested in health-care workers in Liberia, where thousands of Ebola patients have died. Some medical staffers have come down with the virus, despite using protective suits to prevent infection.

The World Health Organization has said it hopes to begin testing experimental vaccines as early as January on more than 20,000 front-line health-care workers and others in West Africa’s hot zone.

Challenges of testing in the field

Still, there are many hurdles to clear before a vaccine becomes a reality. The real test will come if and when the vaccine is used to protect doctors, nurses and other health care workers who treat actual Ebola patients. They are at especially high risk. The WHO says at least 588 health care workers have been infected with Ebola and 337 have died from it.

The chaos caused by the epidemic itself greatly complicates the process of deploying and tracking use of a new vaccine. Working on an expedited timeline, scientists must simultaneously complete two phases of testing — laboratory and field trials — that are usually carried out separately and in a tightly controlled environment.

Because Ebola virus is so deadly, those who receive a trial vaccine must be advised to take all other precautions and protect themselves fully from coming into contact with the virus. This could make it harder for researchers to determine whether the protective clothing and other safety protocols, or the new vaccine, is what conferred protection from the pathogen.

Traditionally, efficacy trials randomly assign participants to receive the vaccine or a placebo (dummy) shot. That’s clearly not ethical here, so some researchers are calling for a “step-wedge” trial, which analyzes what happens to people at similar risk who receive the vaccine at different times. That way, those who have been vaccinated can be compared with others who have yet to receive their shots.d

Vaccine development a ‘silver lining’ of Ebola crisis

Several Ebola vaccines have been in the works for years. But until this current epidemic in West Africa there wasn’t a real push to bring such a vaccine to market and the main source of funding was U.S. biodefense programs aimed at protecting against a biological attack.

“Perhaps one of the only silver linings of the [Ebola] crisis that has shaken West Africa over the past year is that the event has pushed therapeutics and vaccines for [Ebola], which had previously been relatively stalled in development despite the promising results in nonhuman primates, into accelerated production and clinical trials,” Dr. Daniel Bausch, who is not one of the vaccine’s researchers, wrote in an editorial published alongside the trial findings.

The NIH/Glaxo vaccine is also being tested at the University of Maryland, in Britain and in Mali. A different Ebola vaccine, made using a different virus, is being tested at NIAID, part of the National Institutes of Health, and at the nearby Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Meanwhile, a Canadian-developed Ebola vaccine is also currently undergoing human clinical trials in Canada and the U.S., with additional tests to be done in Germany, Switzerland, Gabon and Kenya.

WHO reported on Wednesday that there have been 5,689 Ebola deaths out of nearly 16,000 cases. Almost all cases and all but 15 deaths have been in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia — the three hardest-hit countries, which reported 600 new cases in the past week.