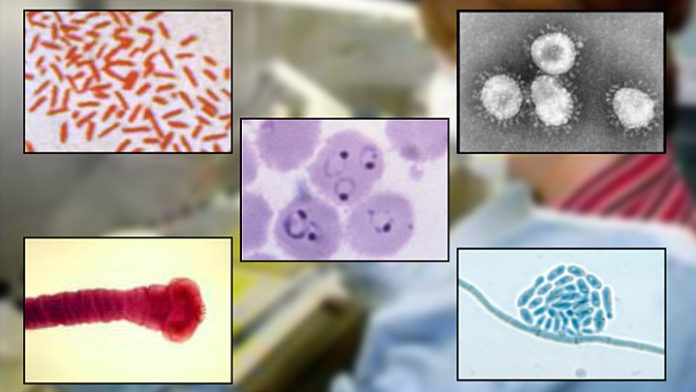

Despite remarkable advances in medical research and treatments during the 20th century, infectious diseases remain among the leading causes of death worldwide for three reasons: 1) emergence of new infectious diseases; 2) re-emergence of old infectious diseases; and 3) persistence of intractable infectious diseases.

Emerging diseases include outbreaks of previously unknown diseases or known diseases whose incidence in humans has significantly increased in the past two decades. Re-emerging diseases are known diseases that have reappeared after a significant decline in incidence. These diseases, which respect no national boundaries, include:

- New infections resulting from changes or evolution of existing organisms

- Known infections spreading to new geographic areas or populations

- Previously unrecognized infections appearing in areas undergoing ecologic transformation

- Old infections re-emerging as a result of antimicrobial resistance in known agents or breakdowns in public health measures.

Within the past two decades, innovative research and improved diagnostic and detection methods have revealed a number of previously unknown human pathogens. For example, within the last decade, chronic gastric ulcers, which were formerly thought to be caused by stress or diet, were found to be the result of infection by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori.

While some emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases receive a lot of publicity — Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Ebola and Avian Influenza, for instance — many others remain dangerously unknown. With the incidence of emerging pathogens and global outbreaks on the rise, it’s never been more important to stay on top of these novel threats.

With that in mind, here are five of the lesser known emerging and re-emerging diseases that pose an ongoing threat to the global population:

Australian Bat Lyssavirus

Australian Bat Lyssavirus is a serious virus that is spread from bats to humans. Discovered in 1996 in several species of bats, this strain of Lyssavirus is similar to the rabies virus and is known to have killed at least three people since 1996, all of whom had contact with an infected bat. Most recently – in February 2013 — an eight year old boy died from the virus in Queensland, Australia, after being bitten or scratched by a bat. Although Lyssavirus infections have thus far been limited to Australia, scientists say that bats anywhere in the world have the potential to carry and transmit the pathogen. Symptoms of the disease include paralysis, delirium, convulsions and death. There are no known effective treatments or cures for Lyssavirus.

Bartonella Infection

Bartonella is a bacteria that can cause several types of diseases in humans. The pathogen is maintained in nature by fleas, ticks and other biting insects; it can be transmitted to humans both by these parasites as well as by bites or scratches from infected cats and dogs. The most commonly known Bartonella-related illness is Cat Scratch Disease, caused by B. henselae, a species of Bartonella that can be carried in a cat’s blood for months to years. Cat Scratch Disease is generally spread by kittens and causes fever, enlarged lymph nodes and pustules at the infection site. Trench Fever, another Bartonella-related illness, is spread by the human body louse and is found worldwide. Though Trench Fever originated in the trenches during World War I, this version of Bartonella is commonly associated with poor and homeless populations. Symptoms of Trench Fever include headaches, fever, rash and bone pain. While Bartonella isn’t new, it’s only in the past couple of decades that researchers have started to discover exactly how pervasive Bartonella infection is in animals and people, with tick bites cited as a common mode of human infection. In fact, some studies suggest that Bartonella could be a hidden cause of many human rheumatic illnesses such as arthritis and chronic fatigue.

Bartonella is a bacteria that can cause several types of diseases in humans. The pathogen is maintained in nature by fleas, ticks and other biting insects; it can be transmitted to humans both by these parasites as well as by bites or scratches from infected cats and dogs. The most commonly known Bartonella-related illness is Cat Scratch Disease, caused by B. henselae, a species of Bartonella that can be carried in a cat’s blood for months to years. Cat Scratch Disease is generally spread by kittens and causes fever, enlarged lymph nodes and pustules at the infection site. Trench Fever, another Bartonella-related illness, is spread by the human body louse and is found worldwide. Though Trench Fever originated in the trenches during World War I, this version of Bartonella is commonly associated with poor and homeless populations. Symptoms of Trench Fever include headaches, fever, rash and bone pain. While Bartonella isn’t new, it’s only in the past couple of decades that researchers have started to discover exactly how pervasive Bartonella infection is in animals and people, with tick bites cited as a common mode of human infection. In fact, some studies suggest that Bartonella could be a hidden cause of many human rheumatic illnesses such as arthritis and chronic fatigue.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpes virus is a cancer caused by the herpesvirus 8, which was first discovered in 1994. It is unknown how the virus is spread but people with suppressed immune systems such as AIDS and cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy often become infected. With the emergence of the AIDS epidemic, the rate of Karposi’s sarcoma in the U.S. increased more than 20 times, peaking at 47 cases per million people annually. Transplant recipients are another group at risk: about 1 in 200 transplant patients in the U.S. develops Kaposi’s sarcoma. Symptoms typically include tumors or skin lesions while respiratory lesions also sometimes occur and can cause shortness of breath, coughing and fever. Furthermore, gastrointestinal lesions lead to weight loss, nausea/vomiting and diarrhea. Kaposi’s sarcoma comes in several forms: Classic KS, endemic KS, HIV related KS and Immunosuppressant related KS. Importantly, endemic KS is not associated with the HIV virus and occurs mainly in young people in sub Saharan Africa. Most cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma result in death; endemic KS, the most deadly form, has a fatality rate of 100 percent within three years.

Enterovirus 71

Enterovirus 71 is a re-emerging infectious disease that was first discovered in California in 1969 and causes outbreaks of severe neurological symptoms in children. Symptoms include rash, fever and respiratory problems but the disease is also known to cause severe neurological symptoms and sudden death. There have been outbreaks in Australia, China and Cambodia in recent years. In fact, in 2012, 66 children became infected in Cambodia, only two of whom survived. A related pathogen, Enterovirus 68, has hospitalized thousands of U.S. children this fall, causing the deaths of at least four young patients.

Nipah Virus

Nipah virus infection is a newly emerging zoonosis (animal-borne disease) that causes severe disease in both animals and humans. The natural host of the virus are fruit bats. Nipah virus was first identified during an outbreak of disease that took place in Kampung Sungai Nipah, Malaysia in 1998. Since then, human-to-human transmission has also been documented, including in a hospital setting in India. Symptoms of infection include fever, headaches, myalgia, vomiting, and sore throat; in some cases, patients also experience acute respiratory syndrome and/or fatal encephalitis. There is no vaccine for either humans or animals. The primary treatment for human cases is intensive supportive care. The case fatality rate of infection with NiV ranges from an average of 40 to 75 percent, however this can vary significantly per outbreak, with recent outbreaks recording fatality rates of up to 100 percent.