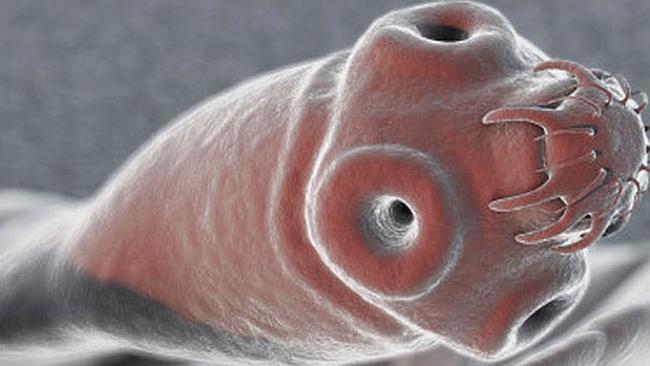

A tapeworm … A man lived with a aparasite in his brain for four years before it was killed by drugs. Picture: Getty Images Source: Supplied

SCIENTISTS in Britain have removed and studied a rare tapeworm that lived in a man’s brain for four years, researchers say.

The “10cm ribbon-shaped” parasite travelled five centimetres from the right side of the brain to the left.

The tapeworm causes sparganosis, an inflammation of body tissues that can cause seizures, memory loss and headaches when it occurs in the brain.

The 50-year-old man went to his doctor in 2008 complaining of headaches, seizures, memory loss and that his sense of smell had changed, The Telegraph reported. Over the next four year the man was tested for a number of diseases including HIV, lime disease and syphilis.

WOMAN SWALLOWS TAPEWORM TO LOSE WEIGHT

Tapeworm … Brain scans show the parasite’s movement in the man’s brain over time. Picture: Genome Biology 2014 Source: Supplied

Surgeons removed it and the patient, of Chinese decent who lives in East Anglia, is now “systemically well”, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute said on Friday.

TAPEWORM TAKES OVER SUSHI LOVER’S BODY

PIG TAPEWORM EGG INFECTED MUSICIAN’S BRAIN

It was the first time the tapeworm, Spirometra erinaceieuropaei, was reported in Britain. Only 300 cases have been reported since 1953.

The tapeworm is thought to be caught by accidentally eating small infected crustaceans from lakes, eating raw amphibian or reptile meat, or by using a raw frog poultice which is a Chinese remedy for sore eyes.

“We did not expect to see an infection of this kind in the UK, but global travel means that unfamiliar parasites do sometimes appear,” said Effrossyni Gkrania-Klotsas of the department of Infectious Disease at Addenbrooke’s NHS Trust.

Lived inside brain four years … Microscopic images of the recovered tapeworm. Picture: Genome Biology Source: Supplied

The team managed to sequence the rare parasite’s genome for the first time, allowing them to examine potential treatments.

“Our work shows that, even with only tiny amounts of DNA from clinical samples, we can find out all we need to identify and characterise the parasite,” Gkrania-Klotsas added.

The doctor said the DNA study underlined the importance of a global database of worm genomes, to help identify and treat parasites.

“This worm is quite mysterious and we don’t know everything about what species it can infect or how. Humans are a rare and accidental host. for this particular worm. It remains as a larva throughout the infection. We know from the genome that the worm has fatty acid binding proteins that might help it scavenge fatty acids and energy from its environment, which may be one the mechanisms for how it gets its food,” Dr Hayley Bennett told The Guardian.

“This genome will act as a reference, so that when new treatments are developed for the more common tapeworms, scientists can cross-check whether they are also likely to be effective against this very rare infection.”

Originally published as Tapeworm in man’s brain four years