The medical tribunal’s considerations over whether to strip the Australian euthanasia campaigner of his medical licence has provoked difficult questions

Can a person’s legal right to take their own life ever be a rational decision to the point that doctors are actually obligated to make no intervention? Should that decision – even if made by a person suffering no terminal illness – then be assisted?

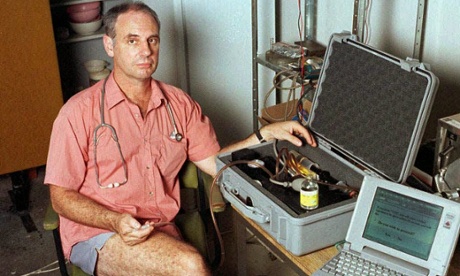

These almost philosophical questions dominated a three-day medical tribunal hearing in Darwin last week, where the doctor and voluntary euthanasia advocate Philip Nitschke was fighting for the return of his suspended medical licence.

The South Australian medical board had taken its emergency action as a result of complaints from other doctors, which were prompted by a news report on ABC’s 7.30 program alleging Nitschke counselled a depressed but otherwise healthy man, Nigel Brayley, who then took his own life in May.

Nitschke said 7.30 had “ambushed” him with emails sent between the two after they met in person, in which Brayley made clear his intentions and offered to send Nitschke his final correspondence. Nitschke had said he would be interested to read it. The emails are noteworthy for the everyday tone of conversation, and lack of any plea for Brayley to think again.

Special counsel Lisa Chapman, acting for the Medical Board of Australia, said Nitschke “did nothing” when told by the healthy man he was going to kill himself, and for that he should lose his right to practise medicine. A doctor has a responsibility to intervene, she argued.

Peter Nugent, a commercial lawyer from Melbourne who is himself suffering a terminal illness, acting for Nitschke, said his client did not have a doctor-patient relationship with Brayley, had never counseled him, and that the suspension had been introduced simply because the board had a distaste for his views and work around voluntary euthanasia.

Nitschke had lobbied for his appeal to be heard in the Northern Territory – arguably the Australian region most supportive of right-to-die legislation – after the South Australian branch of the medical board stripped his licence in July in a midnight meeting.

Polling shows that voluntary euthanasia, which was legal for a short time in the 1990s in the NT, has consistently high support among Australians. A draft bill from the Greens seeks to legalise it for the terminally ill.

The Darwin medical tribunal was not a court of law. If an argument wasn’t working for one side, or was conceded by the other, it was refocused. Reverence of the medical profession frequently jarred with legal precedents. Discussions were clinical, and the impact of a suicide on the family and friends left behind rarely – if ever – got a mention.

Nugent framed the fight as one between the profession’s “doctor knows best” mentality and a person’s free will.

At the heart of all discussions however, was the concept of a “rational suicide”.

Nugent opened by saying this case was about “the dangerous idea [of] whether a person who is contemplating rational suicide ought to be required by a medical doctor not to do so”.

Suicide in itself is no longer a criminal act. Assisting one is, however, which is why people illegally import the drug Nembutal and then take it by themselves, not wanting to get loved ones in trouble. They die alone.

It’s a contradiction in the law, say Nitschke and Nugent.

“Rational suicide” is an extremely controversial cornerstone of Nitschke’s advocacy for voluntary euthanasia which says that the right should not just be for those with a terminal illness. Critics say it has set back the campaign.

While that was still the most common reason people gave to Nitschke for wanting to die on their own terms, some gave “social reasons” such as financial difficulties or being lonely or “tired of life”. Depending on the context of the conversation, these could be “rational” reasons, said Nitschke.

“If I formed the opinion this person would fit the criteria of being rational, I would leave it to them to decide if they would proceed with this lawful act of ending their life,” he said. “I don’t just walk away when they say they’re going to die, to end their life … It’s not a flippant exchange, but it’s not in any way a doctor-patient involvement,” he said.

Nitschke criticised the broadening diagnoses of mental illness, and told the hearing there was no evidence of a definitive connection between suicidal feelings and an illness.

A person’s life – or plans for their death – could not be limited because of the presence of “elements” of a disease such as depression, Nitschke added. A person may be depressed, but that does not mean their wish to die is caused by it.

“Depression can be a serious mental illness and of course it can lead to a person being of unsound mind,” he said. “[But] we’re talking here about degrees of depression. We need to be careful about defining well people as sick.”

“It’s not beneficial to society to pathologise large slabs of behaviour,” he told the tribunal.

Nitschke conceded that if a patient visited him at his surgery and told him they were contemplating suicide he would have an obligation to make a “more rigorous assessment” because they were specifically seeking medical advice, but this obligation did not extend to the people he met through Exit. In those cases, he argued that he was being approached as a euthanasia advocate, not as a doctor.

As he often stressed, his obligation was to not impede them if they were clearly, to his mind, rational.

But the finality of such an action prompted immediate questions. What if a person’s seemingly rational decision was a suicidal idea caused by a mental illness? Does the absence of a doctor-patient relationship justify not making a “rigorous assessment” when confronted with someone who could soon die, leaving behind family and friends?

Tribunal members seemed to genuinely have their thoughts provoked by the discussion. The idea of a rational suicide went against what doctors aim to do – keep people alive.

Nugent argued that Brayley had said he was going to take his own life but he was clearly making a rational decision to do so. Thus Nitschke did not have an obligation to intervene. But that’s not to say he didn’t try.

After their initial introduction at an Exit International workshop Nitschke and Brayley met for a second time at an event at Perth’s town hall, Nugent told the hearing, and Nitschke did indeed suggest Brayley perhaps see a counsellor but the intrusion was firmly rebuffed.

However this meeting had not been mentioned in the multiple media appearances by Nitschke following Brayley’s death – a fact repeated often by Chapman.

One of the emails between Brayley and Nitschke appeared to support the account of the second meeting.

Nitschke made a rational assessment upon meeting Brayley, determined he was competent and rational and so did not impede him, it was claimed.

“If Mr Nitschke had sought in some way to restrain Mr Brayley he would have committed a trespass on him,” said Nugent.

Chapman pushed on what possible assessment Nitschke could have done in such a short time to convince himself that Brayley was not ill, that he was contemplating a “rational suicide”.

Nitschke also disputed that his medical background had any impact. “You’re effectively saying ‘you have medical training therefore you’re doing a medical assessment’,” he told Chapman. “It’s just me, who happens to have medical training.”

Later, under questioning from the tribunal chair, Calvin Currie, It became clearer that Nitschke’s possession of a medical license had a lot to do with reputation.

Nitschke himself conceded he hardly treats any patients as a GP these days, rather concentrating on his work with Exit. But he still wanted his registration back.

“I’m not about to say I don’t use it so let’s throw it away. I’m proud of the degree and I don’t want to lose it for unclear reasons or reasons I feel are unjust.”

When Nitschke confirmed his work would continue with or without a medical registration it became clearer the action taken by the medical board was perhaps more about protecting the reputation of the profession than the immediate safety of the general public.

After all, Nitschke had already said his conduct would not change, but without a license it would not be “a medical professional” advocating voluntary euthanasia.

“Taking away his registration is signalling the board disapproves of his action?” Currie questioned.

“In a sense, yes,” Chapman replied. “The board and the tribunal have an important role and yes, it is about signalling that this person poses a serious risk.”

The suspension was about sending a message.

Outside the tribunal, Nitschke brought up a third holder of a reputation – the information he disseminated to Exit International members and purchasers of his book, the Peaceful Pill.

If his medical registration was revoked, the status shifted. “[It says] that this information is so dangerous people must not have it,” he added.

Brayley’s death was not the simplest case study through which to explore the concept of rational suicide. There were too many elements that didn’t sit right, not least the revelations of the murder investigation.

On the final afternoon of the hearing, Nitschke said he wished he had responded differently to Brayley’s emails. The sequence of events that followed could have been prevented by the addition of a single sentence, he said.

“I would be asking whether you’re certain that this is the set course for you and do you want to talk about it. Had that sentence been in there I suspect the [ABC 7.30] story would never have had the impact it did.”

Whether the tribunal chooses to side with Nitschke and return his registration, or uphold the suspension citing a doctor’s responsibility, Nitschke’s alleged negligence, or even the reputation of the medical profession, it’s a decision that may ultimately be somewhat redundant.

The board revealed early on the director of pro-euthanasia organisation Exit International has been referred to the tribunal on another 12 counts of alleged professional misconduct, so there is every chance this complex, even clinical argument will be had again.

• For information and support in Australia call Lifeline on 13 11 14, Mensline on 1300 789 978 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636. In the UK, the Samaritans can be contacted on 08457 90 90 90. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Hotline is 1-800-273-8255. Hotlines in other countries can be found here.