By Helena Britt, University of Sydney; Christopher Harrison, University of Sydney; Clare Bayram, University of Sydney; Graeme Miller, University of Sydney; Joan Henderson, University of Sydney, and Julie Gordon, University of Sydney

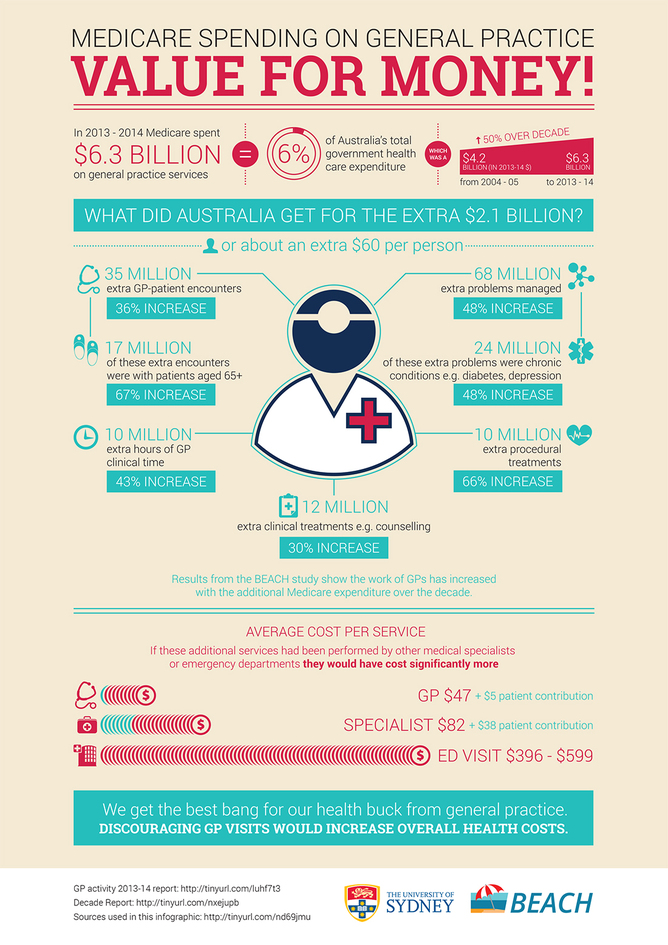

Last year taxpayers spent A$6.3 billion on GP services through Medicare, about 6% of the total government health expenditure. This was a 50% increase (A$2.1 billion) in today’s dollars over the past decade and equates to about A$60 more per person in real terms.

Health Minister Peter Dutton says this growth is “unsustainable”. He plans to introduce a GP co-payment in hope of reducing the number of times Australians visit a GP and to ensure users foot some of the bill.

But targeting primary care for cost savings could backfire. Research we’re releasing today shows that while the number of GP visits has increased, the services are cost-effective. If the same services were performed in other areas of the health system, they would cost considerably more.

Under pressure

Unsustainable or not, Australia’s health-care system faces a number of challenges, most notably from the rising prevalence of chronic conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease and cancer. This is due to three major factors.

- Australia has an ageing population as our world-class health system keeps us alive longer.

- In response to government encouragement through Medicare initiatives, GPs are diagnosing disease earlier and providing preventive interventions for health risk factors and diseases such as hypertension, high cholesterol and type 2 diabetes.

- An increasing proportion of Australians are overweight or obese, putting them at risk for chronic conditions.

Earlier diagnosis means people are living longer with diagnosed disease. The result is exponential growth in required care over their lifetime.

The search for more cost-effective health care for our population should be applauded. But reducing spending on GP services is not the answer.

What do we get?

Our team has been studying general practice activity for over 16 years through the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) program. This cross-sectional encounter-based study uses changing random samples of about 1,000 GPs per year, each of whom contribute details of 100 encounters with consenting patients. This provides a representative sample of about 100,000 encounters per year from across the country.

Results from one of the BEACH books, released today, shed some light on what we got for the $2.1 billion of extra Medicare spending on general practice. In 2013-14 there were 35 million more GP services than ten years earlier, a 36% increase. This included 17 million more attendances by patients aged 65 years and over (a 67% increase).

Length of GP consultations recorded through BEACH suggest that the average consultation now takes almost one minute more than a decade ago. The result is that GPs spend an extra ten million clinical hours with their patients, a 43% increase.

The number of problems managed at these consultations has also significantly increased. GPs managed an additional 68 million health problems at these encounters (an increase of 48%), including 24 million more chronic problems.

Management of these problems involved an additional ten million procedures (a 66% increase) and 12 million clinical treatments, such as counselling, advice and education, than a decade ago.

Clearly, increases in the amount and complexity of GP clinical work are reflected in additional Medicare expenditure. If other medical specialists and/or emergency departments had provided these extra services, they would have cost far more.

The average cost of a GP visit was A$47 from Medicare, plus a A$5 patient contribution. For a private specialist, the average visit costs Medicare A$82 plus a A$38 patient fee.

A visit to the emergency department, which is paid by state and territory governments, costs far more. In Western Australia, for example, an emergency department visit in 2011-12 cost A$599 on average.

More, not less primary care

International research has repeatedly concluded that investment in primary care is the most cost-effective way to provide population health care. As GP services are far cheaper than other types of medical services, discouraging GP visits by introducing a standard co-payment for most patients would increase costs to governments, now and later.

It may seem counter-intuitive, but one effective way to contain the cost of Australia’s health care would be to expand the use of GP services.

One issue not acknowledged in the discussion about health costs is the increasing number of patients with multiple chronic conditions. These patients use more resources and are more likely to have fragmented care due to the number of health professionals involved. GPs play the central role in co-ordinating the management of patients with multiple chronic conditions, reducing costly hospitalisations.

As the age of government-supported retirement increases, many Australians will have to work until they are 70. This highlights the importance of promoting good health across the lifespan, through a strong focus on primary and secondary prevention and co-ordinated management of chronic conditions.

In any one year 85% of us visit a GP, but only about 15% of us are admitted to hospital, where a far greater proportion of health funds is spent. GPs supply the bulk of care to the population, so general practice is where our investment should be.

If we want to strengthen our health-care system and ensure its sustainability into the future, it makes sense to encourage people to use its cheapest and most efficient arm: general practice.

Over the past ten years, the Bettering the Evaluation And Care of Health (BEACH) program has been funded through grants from the Australian Government Department of Health. It has also received financial support from the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, other government instrumentalities, industry and not-for-profit organisations. Funding is paid directly to the University of Sydney and not to any individual.

Clare Bayram, Graeme Miller, Helena Britt, Joan Henderson, and Julie Gordon do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article. They also have no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.