New research by University of Manchester scientists has uncovered key details about what allows some cases of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ (DCIS) — the most type form of non-invasive breast cancer — to resist treatment and come back, often more aggressively. The findings, published online ahead of print in the journal Stem Cells, also reveal a potential new target to improve the effectiveness of radiotherapy for patients with DCIS.

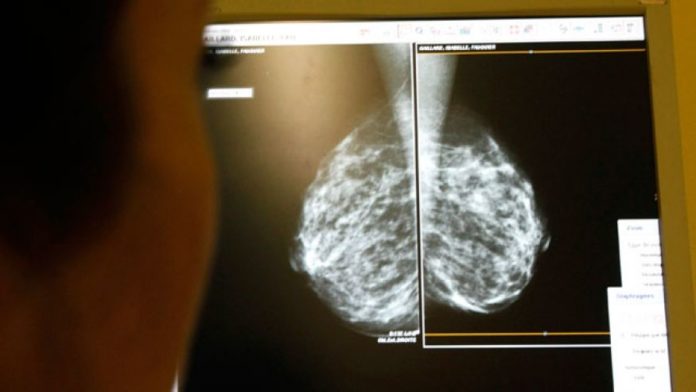

Around 60,000 cases of DCIS, a condition where cancerous cells are contained within the milk ducts of the breast, are diagnosed each year in the United States, with 80 percent diagnosed through breast screening. If left untreated, up to half of DCIS cases could progress into invasive breast cancer.

At this time, health care providers cannot predict which cases of DCIS will progress to invasive breast cancer and which will not, so almost every case of DCIS is treated as potentially invasive. This usually involves breast-conserving surgery (lumpectomy) and, to reduce the risk of the cancer returning, radiotherapy to kill any remaining cancer cells.

However, even with treatment up to one in five patients will see their DCIS come back, either as DCIS or as invasive breast cancer.

“There is still so much we don’t know about DCIS,” said Katherine Woods, Research Communications Manager at the Breast Cancer Campaign, a breast cancer charity devoted to furthering research about the disease. “It is vital that we get a better understanding of the biology of DCIS as well as what makes it return in some women and become invasive breast cancer.”

With the goal of doing just that, researchers from the University of Manchester and University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust – both part of the Manchester Cancer Research Center – investigated the role of a molecule known as FAK in controlling the resistance of DCIS to radiation and in predicting disease recurrence.

“We know that cancer stem cells are able to avoid or repair damage caused by treatment,” said Dr. Gillian Farnie, who led the study at the University’s Institute of Cancer Sciences. “We wanted to look at how FAK is involved in this treatment resistance.”

FAK levels could be used to predict recurrence of DCIS

The team found that cancer cell samples containing more cancer stem cells had increased levels of FAK and that these samples were better able to survive radiotherapy. By examining patient tissue samples and information about whether each person had had a recurrence, the scientists discovered that high FAK activity was linked to the disease returning, either as DCIS or invasive breast cancer.

In further work, a drug that blocks FAK was shown to reduce the formation of mammospheres, or clumps of breast cancer stem cells, indicating that FAK has an important role in cancer stem cell activity. By combining this inhibition of FAK with radiotherapy, the group was able to achieve a greater treatment effect than with either therapy alone.

To see if the FAK drug works in more complex living systems, the researchers gave mice with DCIS a treatment to block FAK. In treated mice, the DCIS was less likely to turn into invasive-like cancer cells. This implies that FAK is important in the progression of DCIS to invasive cancer and thus could serve as a marker for recurrence risk.

“We have shown that blocking the activity of FAK not only reduces the growth of breast cancer stem cells, but also improves sensitivity to radiotherapy,” said Dr. Farnie. “Our findings suggest we can reduce the likelihood of DCIS recurring by inhibiting FAK and measuring FAK levels could offer a method to predict which patients are most likely to experience recurrence.”

Importantly, these findings could help doctors avoid over-treating those patients whose DCIS won’t come back, while at the same time making sure treatment is working for women who need it. Over-treatment of DCIS is of particular concern in the United States, where rates of DCIS are higher than in the rest of the world.