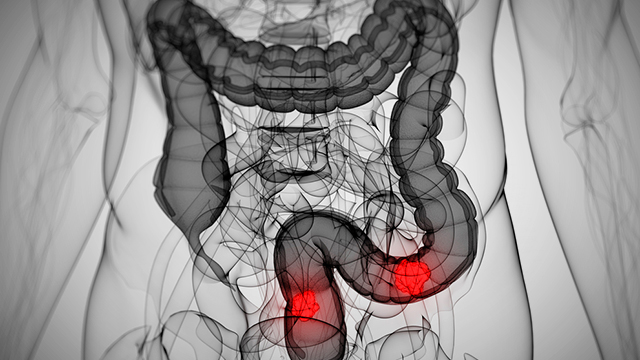

While the number of colon cancer cases has dropped for older Americans, cases among younger adults aged 20 to 49 are rising sharply and are expected to continue climbing over the next 15 years, a new study finds.

If the trends continue, by 2030 the number of colon and rectal cancer cases will roughly double among people between the ages of 20 and 34 years old and grow by 28 percent to 46 percent for people ages 35 to 49 years, according to the analysis.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in the United States and also one of the deadliest, with a significant number of patients dying within five years of diagnosis. According to the National Cancer Institute, nearly 97,000 people will be newly diagnosed with colon cancer and 40,000 with new rectal cancer this year and about 50,000 people will die from those cancers.

Both the incidence and mortality rates of CRC have been decreasing in the United States, a trend that is largely attributed to increased compliance with colonoscopy screening. Currently, the government-backed U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that people ages 50 to 75 get screened for colon cancer using fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. The suggested interval between screenings depends on the method – from fecal tests every year to colonoscopy every ten years.

Patients younger than 50, conversely, are not recommended for general screening, and it is in this group that incidence rates are increasing, say the researchers behind this latest study, published in JAMA Surgery. They note that reports from doctors indicate an uptick in the number of young adults being seen for workups for colorectal cancers. Furthermore, previous studies indicate that these patients are more likely to present advanced forms of CRC, making treatment of the disease much more difficult and reducing the likelihood of positive outcomes.

Causes of increasing CRC rates among young adults remain unclear

To establish current trends in CRC diagnoses, the researchers analyzed data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) for 393,241 patients with CRC between 1975 and 2010 and evaluated the age at diagnosis in 15-year intervals, beginning at age 20. They found that the overall rate of CRC incidence had declined by 0.92% between 1975 and 2010 – by 1.03% in men and 0.91% in women. The reduction was most significant in patients aged 75 and above, declining by 1.15%, compared with a decline of 0.97% in patients aged 50-74.

But although there has been a steady drop in incidence among persons aged 50 years and older, the opposite is true for those in younger age groups, according to the authors, led by principal investigator George J. Chang, MD, an associate professor in the Departments of Surgical Oncology and Health Services Research at MD Anderson. CRC incidence rates went up among patients aged 20-49, increasing by 1.99% in patients aged 20-34 and 0.41% in patients aged 35-49.

On the basis of these trends, the authors estimate that by 2020 and 2030, the incidence rate of colon cancer will increase by 37.8% and 90%, respectively, for patients aged 20 to 34 years. This figure represents a 131.1% incidence rate change of colon cancer by 2030 in younger patients, as compared with patients older than 50 years.

The numbers for rectosigmoid and rectal cancers are similar and are expected to increase by 49.7% and 124.2%, respectively, for this same age subgroup. This extrapolates to a 165% incidence rate change, as compared with older patients. For those aged 35 to 49 years, the incidence rates are also projected to increase, but at a slower pace: 27.7% for colon cancer and 46% for rectal cancer by 2030.

“The increasing incidence of CRC among young adults is concerning and highlights the need to investigate potential causes and external influences such as lack of screening and behavioral factors,” write the authors.

One possible reason for the increase is a delay in early detection of precancerous polyps. Young adults do not undergo routine screening until there is a reason for it — such as a history of familial polyps — and prior to the Affordable Care Act, many young patients lacked health insurance, which may have delayed diagnosis. Younger patients are less likely to be concerned about symptoms and the importance of seeking medical care, the researchers point out. “Their providers are also less likely to consider cancer as a possible diagnosis,” they add. Certain behavioral factors — including physical inactivity, obesity, and poor diet — have also been linked with a higher risk of CRC.

While they still don’t know why the rates are rising, the researchers say new protocols need to be put in place before the numbers worsen. “[T]his report should stimulate opportunities for development of better risk-prediction tools that might help us identify these individuals early and initiate better screening/prevention strategies,” Dr. Kiran K. Turaga, of the Medical College of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, wrote in a related commentary. “The use of stool DNA, genomic profiling, and mathematical modeling might all be tools in the armamentarium of the oncologist in the near future.”