Empa toxicologist Harald Krug has lambasted his colleagues in the journal Angewandte Chemie. He evaluated several thousand studies on the risks associated with nanoparticles and discovered no end of shortcomings: poorly prepared experiments and results that don’t carry any clout. Instead of merely leveling criticism, however, Empa is also developing new standards for such experiments within an international network.

Researching the safety of nanoparticles is all the rage. Thousands of scientists worldwide are conducting research on the topic, examining the question of whether titanium dioxide nanoparticles from sun creams can get through the skin and into the body, whether carbon nanotubes from electronic products are as hazardous for the lungs as asbestos used to be or whether nanoparticles in food can get into the blood via the intestinal flora, for instance. Public interest is great, research funds are flowing — and the number of scientific projects is skyrocketing: between 1980 and 2010, a total of 5,000 projects were published, followed by another 5,000 in just the last three years. However, the amount of new knowledge has only increased marginally. After all, according to Krug the majority of the projects are poorly executed and all but useless for risk assessments.

How do nanoparticles get into the body?

Artificial nanoparticles measuring between one and 100 nanometers in size can theoretically enter the body in three ways: through the skin, via the lungs and via the digestive tract. Almost every study concludes that healthy, undamaged skin is an effective protective barrier against nanoparticles. When it comes to the route through the stomach and gut, however, the research community is at odds. But upon closer inspection the value of many alarmist reports is dubious — such as when nanoparticles made of soluble substances like zinc oxide or silver are being studied. Although the particles disintegrate and the ions drifting into the body are cytotoxic, this effect has nothing to do with the topic of nanoparticles but is merely linked to the toxicity of the (dissolved) substance and the ingested dose.

Laboratory animals die in vain — drastic overdoses and other errors

Krug also discovered that some researchers maltreat their laboratory animals with absurdly high amounts of nanoparticles. Chinese scientists, for instance, fed mice five grams of titanium oxide per kilogram of body weight, without detecting any effects. By way of comparison: half the amount of kitchen salt would already have killed the animals. A sloppy job is also being made of things in the study of lung exposure to nanoparticles: inhalation experiments are expensive and complex because a defined number of particles has to be swirled around in the air. Although it is easier to place the particles directly in the animal’s windpipe (“instillation”), some researchers overdo it to such an extent that the animals suffocate on the sheer mass of nanoparticles.

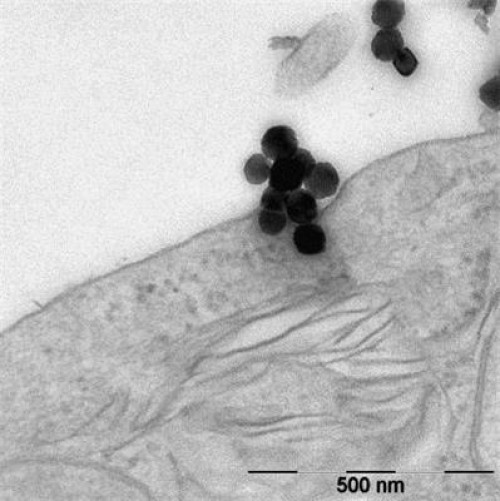

While others might well make do without animal testing and conduct in vitro experiments on cells, here, too, cell cultures are covered by layers of nanoparticles that are 500 nanometers thick, causing them to die from a lack of nutrients and oxygen alone — not from a real nano-effect. And even the most meticulous experiment is worthless if the particles used have not been characterized rigorously beforehand. Some researchers simply skip this preparatory work and use the particles “straight out of the box.” Such experiments are irreproducible, warns Krug.

The solution: inter-laboratory tests with standard materials

Empa is thus collaborating with research groups like EPFL’s Powder Technology Laboratory, with industrial partners and with Switzerland’s Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) to find a solution to the problem: on 9 October the “NanoScreen” programme, one of the “CCMX Materials Challenges,” got underway, which is expected to yield a set of pre-validated methods for lab experiments over the next few years. It involves using test materials that have a closely defined particle size distribution, possess well-documented biological and chemical properties and can be altered in certain parameters — such as surface charge. “Thanks to these methods and test substances, international labs will be able to compare, verify and, if need be, improve their experiments,” explains Peter Wick, Head of Empa’s laboratory for Materials-Biology Interactions.

Instead of the all-too-familiar “fumbling around in the dark,” this would provide an opportunity for internationally coordinated research strategies to not only clarify the potential risks of new nanoparticles in retrospect but even be able to predict them. The Swiss scientists therefore coordinate their research activities with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the US, the European Commission’s Joint Research Center (JRC) and the Korean Institute of Standards and Science (KRISS).

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (EMPA). Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.

Journal Reference:

- Harald F. Krug. Nanosicherheitsforschung – sind wir auf dem richtigen Weg? Angewandte Chemie, 2014; DOI: 10.1002/ange.201403367