Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and a growing economic powerhouse. The capital, Lagos, is home to some 21 million people – almost as many as live in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone combined. When news broke on July 23rd that a case of Ebola had been confirmed in Lagos, the world held its breath. But Nigeria has successfully prevented the feared “apocalyptic urban outbreak.”

In a situation assessment released this week, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Nigeria “free of Ebola virus transmission.” The chains of transmission have been broken, WHO says, because it has been exactly 42 days – double the maximum incubation period for Ebola virus disease – since the last infectious contact with a confirmed or probable case occurred.

“This is a spectacular success story that shows that Ebola can be contained,” the WHO says. The story of how Nigeria prevented further transmission of the virus during the worst outbreak in history is worth telling in detail, says the UN health agency.

This latest success follows another remarkable achievement in Nigeria, when earlier this year the WHO confirmed the country had eradicated Guinea worm disease, a gruesome parasitic infection that causes severe pain and often disability. When the eradication campaign started in 1986, Nigeria had 650,000 of the estimated 3.5 million Guinea worm cases worldwide, more than any other country. In January 2014, the campaign estimated there remained only 148 cases of Guinea worm disease worldwide, marking a complete turnaround in less than three decades.

Many of the strategies Nigeria used to combat Guinea worm disease were also employed in the fight against Ebola. “As sometimes fortunately happens in public health, one success breeds others when lessons and best practices are collected and applied,” the WHO says. The same lessons could prove invaluable to other developing countries, many of which are struggling to best prepare themselves for the possibility of a future Ebola outbreak should the virus cross their borders. Many wealthy countries may also learn a few things from the Nigerian story, despite their more advanced health systems, the WHO notes.

How Ebola started in Nigeria

The outbreak began in Nigeria when a Liberian man infected with Ebola boarded a plane and flew into Lagos on July 20th. He had vomited in the flight, at the airport upon arrival, and in the car that drove him to a private hospital. There, he told staff he had malaria and denied having had any contact with people infected with Ebola – later it was discovered he had. The man died 5 days later.

Believing the patient had malaria, which does not transmit from person to person, the hospital staff attending to him had not worn any protective equipment. Nine became infected and four of them died, as did the man who had escorted the patient to the hospital. There was a second outbreak at Port Harcourt, the capital of Rivers State and Nigeria’s oil hub, when on August 1st, a close contact of the Lagos index patient arrived by plane and sought help from a private doctor. The doctor developed symptoms 9 days later and died of Ebola on August 23rd. In total, 19 people became ill in Nigeria, seven of whom died.

The areas highlighted in red represent the locations of confirmed Ebola cases in Nigeria.

But as soon as the virus was confirmed, a massive public health effort began. Containment has been key to ending every Ebola outbreak in Africa in the past. Every person who may have been exposed to the virus has to be found, monitored and isolated if they develop symptoms. When Nigerian authorities, with help from the WHO, studied the contacts involved, they discovered an alarming number of high and very high-risk exposures for hundreds of people. It was clear that all available resources had to be mobilized immediately to stop the outbreak.

Contact tracing

One of the first challenges facing health officials was to trace all the people who had come into contact with infected Ebola patients — a daunting task in Lagos, the largest city in Africa, with a population of 21 million. Residents live in crowded, unsanitary conditions, many in slums. Also, for work and to sell their goods, thousands of people travel in and out of the city every day. The US consul general in Nigeria, Jeffrey Hawkins, said at the time: “The last thing anyone in the world wants to hear is the two words ‘Ebola’ and ‘Lagos’ in the same sentence.” That juxtaposition, he added, conjured up images of an “apocalyptic urban outbreak”.

But such an appalling prospect was averted. More than 150 people were sent out to look for contacts of people who had become ill and GPS systems were used for tracking Ebola contacts. With help from the WHO, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other organizations, Nigerian authorities managed to reach 100% of known contacts in Lagos and 99.8% in Port Harcourt. It was, said WHO, “world-class epidemiological detective work”.

According to a paper written by some of those involved, the list of contacts reached 898 and they were not all in Lagos. A nurse who became infected traveled more than 310 miles (500km) to Enugu, finding at least 21 contacts. But the biggest crisis was caused by one of the index patient’s contacts, who had been infected, fleeing to the oil capital, Port Harcourt, where he infected a doctor. That doctor, who died, was linked to 526 contacts, including many members of his church who carried out a healing ceremony for him involving the laying on of hands.

Prompt set-up of isolation, treatment and real-time reporting systems

Another important feature of Nigeria’s success was that federal and state governments very quickly provided financial and material resources, and well-trained and experienced staff. They immediately set about constructing isolation wards and then designated Ebola treatment centers. Vehicles and specially adapted mobile communications systems were made available and greatly assisted real-time reporting of the changing situation.

Unlike in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, in Nigeria, all identified contacts were monitored on a daily basis for the maximum incubation period of Ebola – 21 days. In total, the contact tracers made 18,500 face-to-face visits to check on people for raised temperature, which can indicate the onset of symptoms, – not easy given the stigma around the disease. Their persistence – anybody who fled the monitoring teams was tracked down and returned to medical supervision – and disinfection of premises paid off.

Strong leadership, funding and response coordination

WHO suggest the most critical factor in Nigeria’s successful response to the Ebola outbreak was “leadership and engagement from the head of state and the Minister of Health,” followed by generous allocation and quick disbursement of government funds.

Local volunteers working with CDC staffers gather for a meeting on Ebola preparedness in Lagos, NIgeria.

Another big factor, say WHO, was strong partnership with the private sector, as was rapid involvement of the Nigerian Center for Disease Control (NCDC) and the prompt establishment of an Emergency Operations Center, supported by local WHO officials. Nigeria also has a first-rate virology laboratory that is affiliated to the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. The lab was quickly staffed and equipped to reliably diagnose Ebola cases so containment could proceed promptly.

Coupled with high-quality contact tracing by experienced epidemiologists, these factors ensured cases were detected early and quickly isolated, greatly reducing the chance of further transmission.

Communication with the general public

Nigerian authorities were quick to put out messages to the general public, the idea being that this would get communities to support the containment measures. CDC staffer Lisa Esapa, who worked on the ground to help stop the outbreak in Nigeria, wrote about the challenges they faced in communicating these messages:

Talking to people, you can tell they are nervous and scared. Part of the work of the Emergency Operations Center is to put out accurate messages on prevention and counter the misinformation about Ebola that circulates. For example, the current rumor is that drinking salt water can prevent Ebola. There is a lot of stigma around Ebola and anyone associated with the disease.

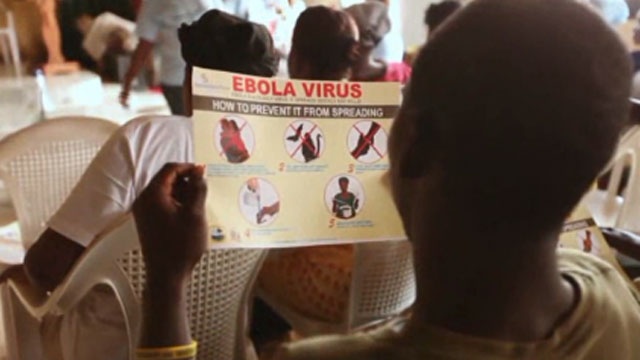

Public information campaigns were cited as a key part of Nigeria’s successful Ebola response strategy.

Health officials used a variety of initiatives to get out the key facts about Ebola on different media, hoping that education would help to overcome the stigma. House-to-house and local radio campaigns – using local dialects – explained the risks, how to take personal preventive measures and what was being done to control virus spread. President Goodluck Jonathan also appeared on television newscasts to reassure Nigeria’s vast and diverse population. Also, messages were put out on social media, and well-known “Nollywood” movie stars were enlisted to give out Ebola facts on television.

Drawing on the success of Nigeria’s polio eradication program, traditional, religious and community leaders were engaged early on and played a critical role in raising public awareness.

Polio eradication strategies ‘re-purposed’ for Ebola control

Nigeria is in the midst of implementing one of the world’s most innovative polio eradication programs. Re-purposing the infrastructure of the program also helped the country avoid an Ebola disaster.

Nigeria’s polio eradication program makes use of cutting-edge GPS technology to ensure no child misses out on polio vaccination. The country, which passed through the high-transmission season with only 1 single case of polio detected by a finely-tuned and sensitive surveillance system, is on track to interrupt wild poliovirus transmission from its borders before the end of 2014, the WHO says.

When Nigeria’s first Ebola case was confirmed in Lagos in July, the authorities immediately re-purposed the polio eradication infrastructure and technology to trace Ebola cases and contacts. Using the latest GPS technology, the Nigerians, with help from WHO, were able to quickly trace contacts and map links between identified chains of transmission. Eventually, every single one of the country’s 19 confirmed cases was linked back to direct or indirect contact with the air traveler who brought Ebola to Lagos from Liberia on July 20th.

WHO Director-General, Dr. Margaret Chan, says Nigeria’s achievements have a very clear message:

“If a country like Nigeria, hampered by serious security problems, can do this – that is, make significant progress towards interrupting polio transmission, eradicate guinea-worm disease and contain Ebola, all at the same time – any country in the world experiencing an imported case can hold onward transmission to just a handful of cases.”