Breakthrough by Australian surgeons at St Vincent’s hospital could save the lives of 30% more heart transplant patients

In a world first, Australian surgeons have successfully transplanted “dead” hearts into patients at Sydney’s St Vincent’s hospital.

The procedure, using hearts that had stopped beating, has been described as a “paradigm shift” that will herald a major increase in the pool of hearts available for transplantation. It’s predicted the breakthrough will save the lives of 30% more heart transplant patients.

Until now, transplant units have relied solely on still-beating donor hearts from braindead patients. But the team at St Vincent’s Hospital heart lung transplant unit announced on Friday they had transplanted three heart failure patients using donor hearts that had stopped beating for 20 minutes.

Two of them have recovered well, while the third, who recently undertook the procedure, is still in intensive care.

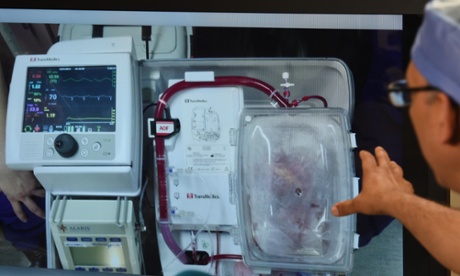

Cardiologist and unit director Peter MacDonald said the donor hearts were housed in a portable console dubbed a “heart in a box”.

Here they were submerged in a ground-breaking preservation solution jointly developed by the hospital and the Victor Chang cardiac research institute.

The hearts were then connected to a sterile circuit where they were kept beating and warm.

Cardiothoracic surgeon Kumud Dhital, who performed the transplants with hearts donated after circulatory death (DCD), said he “kicked the air” when the first surgery was successful.

It was possible thanks to new technology, he said. “The incredible development of the preservation solution with this technology of being able to preserve the heart, resuscitate it and to assess the function of the heart has made this possible,” he told a press conference on Friday.

The first patient to have the surgery done was Michelle Gribilas. The 57-year-old Sydney woman was suffering from congenital heart failure and had surgery about two months ago.

“I was very sick before I had it,” she said. “Now I’m a different person altogether. I feel like I’m 40 years old. I’m very lucky.”

The second patient, Jan Damen, 43, also suffered from congenital heart failure and had surgery about a fortnight ago. The father of three is still recovering at the hospital.

“I feel amazing,” he said. “I’m just looking forward to getting back out into the real world.”

The former carpenter said he often thinks about his donor. “I do think about it, because without the donor I might not be here,” he said. “I’m not religious or spiritual but it’s a wild thing to get your head around.”

MacDonald said the team had been working on this project for 20 years and intensively for the past four.

“We’ve been researching to see how long the heart can sustain this period in which it has stopped beating,” he said. “We then developed a technique for reactivating the heart in a so-called heart in a box machine.

“To do that we removed blood from the donor to prime the machine and then we take the heart out, connect it to the machine, warm it up and then it starts to beat.”

The donor hearts were each housed in this machine for about four hours before transplantation, he said. “Based on the performance of the heart on the machine we can then tell quite reliably whether this heart will work if we then go and transplant it.

“This breakthrough represents a major inroad to reducing the shortage of donor organs.”