A Liberian Ebola patient was left in an open area of a Dallas emergency room for hours, and nurses treating him worked without proper protective gear and faced constantly changing protocols, according to a statement released by the nation’s largest nurses’ union.

Among those nurses was Nina Pham, 26, who has been hospitalized since Friday after catching Ebola while caring for Thomas Eric Duncan, the first person diagnosed with the virus in the U.S. He died last week.

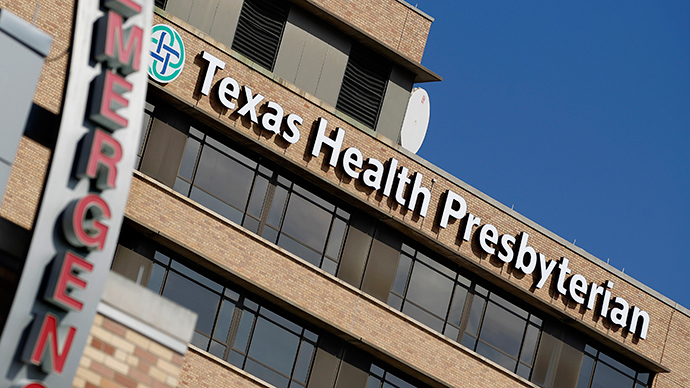

Public-health authorities announced Wednesday that a second Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital health care worker had tested positive for Ebola, raising more questions about whether American hospitals and their staffs are adequately prepared to contain the virus.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said some breach of protocol probably led to Pham’s infection, but National Nurses United contends the protocols were either non-existent or changed constantly after Duncan arrived in the emergency room by ambulance on Sept. 28.

According to the Associated Press, Duncan’s medical records show that Pham helped care for him throughout his hospital stay, including the day he arrived in intensive care with diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, and the day before he died. Hospital records make numerous mentions of protective gear worn by hospital staff, and Pham herself notes wearing the gear in visits to Duncan’s room, AP reports. Importantly, however, there is no indication in the records of her first encounter with Duncan, on Sept. 29, that Pham donned any protective gear.

Deborah Burger of National Nurses United, who convened a press conference to relay what she claims are concerns of nurses at the hospital, said they were forced to use medical tape to secure openings in their flimsy garments and worried that their necks and heads were exposed as they cared for Duncan.

She said the statement came from “several” and “a few” nurses, but refused repeated inquiries to state how many. She said the organization had vetted the claims, and that the nurses cited were in a position to know what had occurred at the hospital. She did not specify whether they were among the nurses caring for Duncan.

The nurses allege that his lab samples were allowed to travel through the hospital’s pneumatic tubes, possibly risking contamination of the specimen-delivery system. They also said that hazardous waste was allowed to pile up “to the ceiling”.

The statement went on to describe how nurses had to “interact with Mr. Duncan with whatever protective equipment was available,” even as he produced “a lot of contagious fluids.” Duncan’s medical records underscore that concern. They also said nurses treating Duncan were also caring for other patients in the hospital and that, in the face of constantly shifting guidelines, they were allowed to follow whichever ones they chose.

The hospital has not responded to specific claims by the nurses but said they would “review and respond to any concerns raised by our nurses and all employees.”

When Ebola was suspected but unconfirmed, a doctor wrote that use of disposable shoe covers should also be considered. At that point, by all protocols, shoe covers should have been mandatory to prevent anyone from tracking contagious body fluids around the hospital.

Duncan first sought care at the hospital’s ER late on Sept. 25 and was sent home the next morning, despite a 103 degree fever. He was rushed by ambulance back to the hospital on Sept. 28. Unlike his first visit, mention of his recent arrival from Liberia immediately roused suspicion of an Ebola risk, records show.

The CDC said 76 staff members at the hospital could have been exposed to Duncan after his second ER visit. Another 48 people who may have had contact with him before he was isolated are also being monitored. Pham remained hospitalized Tuesday in good condition and said in a statement that she was doing well. The second nurse infected with Ebola, identified as Amber Vinson, was transferred to a special treatment unit at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, where American aid workers Nancy Writebol and Dr. Kent Brantly were treated for the deadly virus in August.