Thomas Duncan was released from hospital with 103F degree fever, despite telling nurse about recent travels

Thomas Duncan, the first person to die of Ebola in the US, was released from hospital with a 103F fever on his first visit, despite telling a nurse he had recently travelled from Africa and exhibiting key symptoms of the deadly virus, it was revealed on Friday.

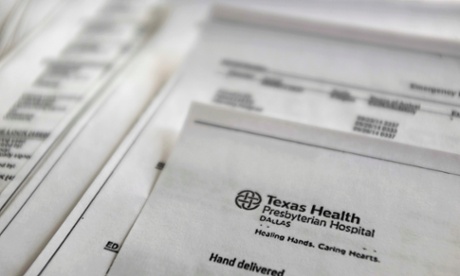

Duncan, a Liberian national, was released from Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital even though his fever spiked on his first visit to the emergency room on 26 September, according to his medical records obtained by the Associated Press. A “physician’s note” from the visit says Duncan was “negative for fever and chills” despite having a 103F (39.4C) temperature.

The family provided the AP with more than 1,400 pages of Duncan’s medical records, which apparently chronicle the events that ultimately culminated in his death at 7.51am on Wednesday.

Duncan arrived in Dallas from Liberia on 20 September to be reunited with Louise Troh, the mother of his child whom he intended to marry. A few days later, Duncan fell ill. He went to Texas Health Presbyterian hospital in Dallas, complaining of abdominal pain, dizziness, a headache and decreased urination, according to the AP. The records show that Duncan reported his level of pain was eight on a scale of 10. Doctors ran a series of tests, ruling out appendicitis and a stroke, among other ailments.

When the examination was over, the doctors prescribed him antibiotics and told him to take Tylenol, an over-the-counter drug designed to relieve pain and fever. Duncan returned home to the apartment he was sharing with Troh and her relatives.

Four days after he first began feeling sick, his condition worsened and he was rushed to the hospital by ambulance, where he was admitted and quickly placed in isolation. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) confirmed last Tuesday that Duncan had tested positive for Ebola.

Over the weekend, Duncan’s liver function declined, he was placed on dialysis and was breathing through a respirator. The hospital began treating Duncan with the experimental antiviral drug brincidofovir. On Wednesday, Duncan died.

It is still not clear why the hospital did not test Duncan for Ebola on his first visit, based on his travel history and symptoms. The hospital initially said Duncan had not told them of his travel history, and then later said he had, but the nurse had not shared that information with the entire medical team. The following day, the hospital changed its story again, attributing the error to a “flaw” in its online health records system, but then corrected its statement and said their was “no flaw” and Duncan’s travel history had been available to the entire medical team.

Many in the community are raising questions about the standard of care Duncan received, and some believe his race and lack of insurance played a role in the hospital’s decision to send Duncan home, feverishly ill with a course of antibiotics.

The hospital defended itself in a statement on Thursday saying, “Our care team provided Mr Duncan with the same high level of attention and care that would be given any patient, regardless of nationality or ability to pay for care. In this case that included a four-hour evaluation and numerous tests. We have a long history of treating a multicultural community in this area.”

As questions linger over Duncan’s death in the US, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced a grim milestone in the current Ebola outbreak – the disease has claimed more than 4,000 lives since the outbreak began in March 2014.

The WHO report noted that the exposure of health care workers to the virus “alarming feature of this outbreak”. More than 400 health care workers have developed Ebola since the outbreak began, including three American medical missionaries who contracted the virus while working at a hospital in Liberia and an American doctor with the WHO who contracted it in Sierra Leone and is still being treated in an Atlanta hospital.