Marie McInerney reports:

One of the much loved traditions at the Australian Indigenous Doctor’s Association conference each year is the presentation to new medical graduates of special stethoscopes – in the colours of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags.

This year, for the first time, they also marked an intergenerational milestone.

Australia’s first Indigenous doctor, Professor Helen Milroy (now a Commissioner in the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse) and Associate Professor Noel Hayman, one of Queensland University’s first medical graduates, presented them to their respective graduating daughters.

AIDA President Dr Tammy Kimpton said another five current medical students had parents who were Indigenous doctors. There are also a growing number of sibling medicos: including Professor Alex Brown and Professor Ngaire Brown, Dr David Murray and Dr Anthony Murray, and the three Kong siblings (see story below).

Kimpton told the conference that the number of Indigenous doctors in Australia has doubled over the past nine years to 204. That’s still way behind population parity (2,895 to represent 3 per cent of doctor numbers in Australia) but medical student enrolment numbers have been at parity since 2011.

Supporting students so they can get through their studies and graduate has been a big issue: an important factor in growing the numbers has been the collaborative agreements struck by AIDA and medical colleges around Australia, and the role of mentoring, by Indigenous and non-Indigenous medical staff and students, and AIDA itself.

Three of AIDA’s leading lights – medical pioneer Dr Louis Peachey, Australia’s first Indigenous surgeon Professor Kelvin Kong, and anaesthetist Dr Dasha Newington – talk below about the support they received and challenges they faced in their medical journeys.

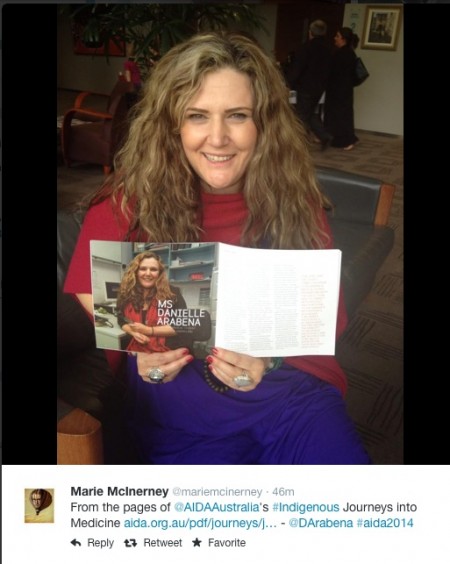

You can read more about groundbreaking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors in this AIDA publication, Journeys into Medicine.

You can read more about groundbreaking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors in this AIDA publication, Journeys into Medicine.

The conference also featured a workshop on mentoring, which showcased different approaches, including the successful Flinders and Adelaide Indigenous Medical Mentoring (FAIMM) program in south Australia. This brings together doctors and students over pizza and a chat and visits high schools to encourage Indigenous students to think about health careers.

***

Dr Louis Peachey, Senior Medical Officer, Atherton Memorial District Hospital

Mentoring is intrinsic both to my profession and my culture. One of the really interesting things for me when I first went to medical school was that, on the one hand, it was entirely, utterly foreign culture for me, so different from anything I was used to, extremely white.

But at the same time there was a relationship between pupil and teacher that was very close to the relationships I knew in Aboriginal culture between uncle and nephew.

I started medical school in 1985. Professor Sandra Eades and I were in the same year at Newcastle Uni and we – and Professor Ian Anderson who was studying at Melbourne Uni – graduated next after Helen Milroy (the first Indigenous doctor in Australia). So we were tied for second place!

I’m not even sure I could say I wanted to do medicine. I was working in the Aboriginal Development Commission, a predecessor to ATSIC and one of the officers there told me that Newcastle had opened up four places for Murri students in their medical school and asked if I was interested. I said of course, but had no idea about it all: I had to look up my Jacaranda atlas to see where Newcastle was.

I had some reservations based on what had happened with Aboriginal teacher training at the time. (Prime Minister Malcolm) Fraser had the best of intentions, but state governments, particularly Queensland, just abused it, and were having black teachers for black kids where no white teacher wanted to go anyway. My grandfather and great grandfather fought so hard for their freedom so it would have been disrespectful to enter another form of indentured servitude.

But they told me that, no, a group of their own Third Year students had been doing a population health project, so set out to count up all the Aboriginal doctors they could find, and found just one senior student in Western Australia (Helen Milroy). They thought: ‘there’s a lot we can’t do for Aboriginal health, but we can do this: let’s fix the thing we can fix.’ That sounded pretty good to me.

I was 19 when I went. It was terribly daunting. I’m not sure I was articulate enough at the time to identify a cultural element, but there was a bit of me that felt very strongly that an ‘Aboriginal from the jungle’ should never have stepped out of it. There was a tiny number of people, three other students really, who were prone to showing overt racism.

As it turned out, each of these guys has become incredible model citizens and campaigners for civil rights. I was really annoyed at the time, but they were just privileged white kids: they weren’t trying to hurt anyone, to them they were just being larrikins. I know the men they became were utterly different to the kids they were at medical school.

There are still a lot of things that need to be corrected but I think this generation of Indigenous doctors has shifted things in the last 25 years. I think we’ve managed to establish we are not a permanent underclass, that we can step up and be equal to everyone else.

The incredibly important thing for me in my acceptance within my own college (ACRRM) is that I’m not there as a mascot, I’m not there because they felt sorry for me, I’m there because that’s my club, that’s my group.

What are the main things that helped me get through medical school? I don’t want to ram religion down anyone’s throat, but I have to say the most important thing was a very strong unshakeable faith in an incredibly generous and loving God.

Number two would be the extraordinary support system around me, a huge group of lovely, generous, good people in the medical school that made it happen. I got truly astonishing support.

***

Associate Professor Kelvin Kong, Australia’s first Aboriginal surgeon who specialises in ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgery

My father, who is Chinese, was a doctor and my mother, who is a Worimi woman (from Port Stephens in New South Wales), was a nurse. I’m the first Aboriginal surgeon in Australia in a Western sense.

My father, who is Chinese, was a doctor and my mother, who is a Worimi woman (from Port Stephens in New South Wales), was a nurse. I’m the first Aboriginal surgeon in Australia in a Western sense.

We do have our Ngangkari (traditional healers): these days they are more associated with mental and spiritual wellbeing but in years past they were proceduralists as well.

While I’m acknowledged as the first Aboriginal Fellow of the College of Surgeons, they were working long before me and I pay my respects to that.

In truth I think I’d much rather be celebrated as the 100th Aboriginal surgeon than the first. I think it’s a travesty to Australia that it has taken so long to get to this point. By the same token, I’m very privileged and elated that I’ve been bestowed with such wonderful opportunity. I’m only here because of the opportunities I’ve been given and the support people put around me.

The three things that were most crucial? That’s easy: my nan, my mum and my sisters – Marilyn (Clarke), who is Australia’s first Indigenous obstetrician and gynaecologist and Marlene (who is a Public Health Physician Trainee and GP). They were my mentors.

My nan had insight, pulled me out of footy and said go to uni and study. My mother and father separated when I was two or three so my influence towards health came more from my mother. Everyone in the community used to come to our house for health issues: in later years I’d wish they would leave us along, we didn’t have enough time with mum as it was, but when we were young we’d be fighting over who was going to cut the sutures, put on the bandages. It was a natural progression into health, Mum was such a natural healer.

Another huge influence came when I was in Year 8 and we went to a function at Newcastle Uni, and heard two amazing speakers: my hero Louis Peachey and Sandra Eades. I realised medicine didn’t have to be a white person/private school pathway.

Mentoring came in many ways, introductions to someone, sitting down with my CV to see what research I should do, how to get published, how to do presentations, how to get invited, how to meet surgeons. The medical profession is perceived as an old boys network, but it’s just about breaking down barriers in small steps to get access to the process.

Of course you face different challenges as Indigenous student. Cultural safety is a big issue. Aboriginal Australians are not regarded as having academia high on their list, so you get statements like ‘Yeah, but you’re not like them’. That’s extremely offensive to me, I’m exactly like them. Or you get ‘you’re only there because you’re black’. Sometimes you feel like you have to do things ten times better than your peers to prove your worth. I think that’s where I was lucky from mentors that they allowed me to see past that and be able to keep focused on my goal, and also to enjoy the journey, because it’s fun.

In formal and informal processes, I’ve always tried to look after those who follow in my footsteps. I’m now at stage of my career where I’m not only a mentor or role model to Indigenous kids, but to non-Indigenous students and doctors as well.

To see someone like Dash come through the ranks is so exciting: to see her passion and how smart she is, and where I see her being in five or ten years time. I met her through AIDA, at one of these conferences. There aren’t many places where medical students get to meet with consultants so AIDA creates a place for that.

Although she’s in a very different field with anaesthesia, there are many things I can do to help both from cultural and medical perspective I don’t have the specialist knowledge in the field but I can certainly influence people who do to support and guide her.

In five years time, Dash will have a mentee like her sitting beside her, like we are tonight. She’s so powerful, strong, smart, enthused, already you see her mentoring some of the younger ones.

The problem with a lot of our community, and it shouldn’t be a problem, is we’re not boisterous because we’ve always been shouted down, or we’re shy or shamed. That can be hard in a competitive environment like health where you’ll get help if you jump up and down, and if not, you’ll get ignored, fall through cracks. My experience is that mentoring programs that seem to work are those that naturally occur, not through formal relationships that are forced upon you, but that may have been flaws in the programs that I’ve seen. For one mentor of mine, all he did was say ‘G’day Kelv’ in the hospital corridor: acknowledged me and my presence.

There are a whole lot of reasons why a mentoring relationship might not work: personality clash, influences beyond your control, different career decisions. There needs to be a way to gently or politely walk away without offending either mentor or mentee, without ruining the relationship and, most importantly, without ruining the dream.

***

Dasha Newington, a Critical Care Resident at Launceston General Hospital who has been accepted into the Tasmanian Anaesthetic Training Program for next year

I don’t have a formal mentoring relationship with Kelvin, but he’s a real role model and has given me lots of advice and support over the years. You’ve got to understand that all Indigenous students and graduates look up to him: you grow up not so much idolising him, but filled with respect and wanting to be like him.

I don’t have a formal mentoring relationship with Kelvin, but he’s a real role model and has given me lots of advice and support over the years. You’ve got to understand that all Indigenous students and graduates look up to him: you grow up not so much idolising him, but filled with respect and wanting to be like him.

A lot of us don’t believe in ourselves when we’re young. Kelvin got that sense of possibility when he met Louis and Sandra when they were medical students, but it doesn’t happen to all of us. We grew up not even thinking of it as an option. I never thought about uni. I finished school, went to work in McDonalds, became a manager.

Then I needed to go to hospital for skin grafts for burns. The doctors were good at the skins grafts but it was a really bad experience for me culturally. They were really racist, referring to my circumstances in terms of ‘they’re always drinking, they do these things to each other, treat their women bad’. They didn’t say anything explicitly but it was like I was a second class citizen. I thought I can do a better job than that, I can be better for our mob than that, our mob doesn’t have to go through this when they have tough times.

Being part of AIDA has been a big thing for me. I was pretty lonely at medical school. There were some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and we stuck together, but there wasn’t a formal mentoring arrangement. But it must have been nothing compared to what Helen Milroy or Sandra Eades or Louis Peachey faced in the early days when they were on their own. AIDA has done good work to set up support processes for Indigenous students in collaboration with medical schools.

One of the issues with mentoring is the power differential, where sometimes the mentee feels they can’t approach their mentor easily. It can be too hard to ring a consultant and ask for help. Having informal gatherings is a good way to manage that.

I had one experience of being allocated to a mentor at uni but it didn’t work for me. I didn’t know how to get out of it, so I spoke to Auntie Ngaire (Brown – a member of the Prime Minister’s Indigenous Advisory Group) and reached out to others. I learn also from the younger ones coming through the ranks, particularly as the ranks get bigger and bigger.

As a student I got a lot of support, but I worry a little that graduates can be lost in the wilderness when they got into internship and residency. I was very fortunate. Professor Kate Leslie invited me to Melbourne for a week. I was terrified, because she’s quite famous, but I had the most wonderful week. As an Aboriginal doctor, the Aboriginal people in our lives are inspiring, but so too have been non Indigenous people who have been part of my support journey.

When I first tried anaesthesia, I just loved it. With everything else in medicine I was, like, ‘I don’t know if I can do this forever’. Anaesthesia was different. I knew this was for me from the start. I have had a bit of pressure from the community to go out and be a GP, because that’s what our mob needs, but we need specialist people too and we need to have culturally safe spaces in hospitals.

Anaesthesia is all about relieving pan and suffering. For our mob, it’s also about allaying their fears about being put to sleep. A lot of Aboriginal people come into hospital and never go home, so they’re really scared. Hospitals haven’t taken good care of our mob really well in the past, so there’s an extra layer of anxiety. We can make a difference for those patients.

I want all Aboriginal kids to grow up, to have dreams and know they can achieve them. Telling positive stories, the good stories coming out of places like AIDA, is a way to encourage that, and not focusing on the negatives.

(The photo above was taken during a visit to a NSW school in Bourke – teaching the kids about health and promoting health careers.)

• You can track Croakey’s coverage of the conference here.