It’s so dark that as soon as the door clicks shut, you can’t see your hand in front of your face. There are no windows. All that’s visible are glimmers of light flickering under the door as a prison guard walks past your cell.

This was the reality lived by former prison inmate Brett Collins, who spent more than 60 days locked in so-called ‘black cells’ in Grafton, Maitland and Long Bay jails in the 1970s.

Collins was sentenced to 17 years’ jail with an eight-and-a-half-year non-parole period, after being convicted of armed robbery and assault in Sydney in December 1971.

He estimates he spent about five of the 10 years he served in prison in solitary confinement, both in so-called ‘black cells’ that had no windows or natural light, and in segregated cells that did have lighting.

Being sent to solitary

In New South Wales, an inmate may be placed in solitary confinement if they are deemed a threat to the personal safety of any other person, or the security or good order of a correctional centre, as outlined in 1999’s Crimes Act, which governs Corrective Services New South Wales’ actions.

In New South Wales, an inmate may be placed in solitary confinement if they are deemed a threat to the personal safety of any other person, or the security or good order of a correctional centre, as outlined in 1999’s Crimes Act, which governs Corrective Services New South Wales’ actions.

Solitary confinement, officially known as ‘segregated custody’, is when an inmate is detained in isolation from all other prison inmates in a segregated cell for all or nearly all of the day, with minimal environmental stimulation.

A different form of segregation involves cells that are referred to as ‘assessment cells’, which are used to house inmates who are at risk of self-harm. These cells are under camera observation, and the inmate is managed on a detailed management plan by a Risk Intervention Team.

Brett Collins believes he was placed in solitary confinement because he wrote complaints to the NSW Law Society that he had been treated unfairly by a prison governor – this was deemed an untrue statement and Collins was charged.

Collins says he was also moved around and placed in segregated custody in various prisons across New South Wales because he says he was “seen as a problem” by prison authorities as he spoke for prisoners as one of their representatives at a local and state level.

The solitary mind: impact on mental health

Inmates held in solitary confinement experience a range of mental health problems including anxiety, panic, insomnia, paranoia, aggression and depression.

Inmates held in solitary confinement experience a range of mental health problems including anxiety, panic, insomnia, paranoia, aggression and depression.

Don Grant, a forensic psychiatrist formerly with the Queensland Community Forensic Mental Health Service, says these psychological effects are the result of: social isolation, which can lead to further withdrawal; boredom and sensory deprivation, which cause brain activity to slow; and a lack of control with no personal autonomy, which may lead to a loss of self-reliance and dysfunction in social situations when an inmate is released.

Long-term isolation with a lack of physical activity, social interaction and visual stimulation has been shown to lead to depression and stress, and a change in brain structures as a consequence. In particular, the hippocampus, the part of the brain used in memory and decision-making, shrinks dramatically in the brains of people who are depressed or stressed for extended periods. There is also evidence that the longer people remain depressed and untreated, the more their hippocampus shrinks, and they have difficulty controlling stress and their emotions.

In 2011, Juan Mendez, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, called for a worldwide ban on the practice of prolonged solitary confinement except in very exceptional circumstances and for as short a time as possible, with an absolute prohibition in the case of juveniles and people with mental disabilities.

Mr Mendez concluded that even 15 days in solitary confinement constituted torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, and 15 days is the limit after which irreversible harmful psychological effects can occur.

How many prisoners are in solitary confinement?

The number of prisoners held in solitary confinement across Australia is not reported or released in any system-wide way.

The number of prisoners held in solitary confinement across Australia is not reported or released in any system-wide way.

In NSW, where Brett Collins was imprisoned, a Corrective Services spokesperson says they cannot provide a figure for how many people are currently in segregated custody.

“It’s not a case we don’t keep a record of it; we keep a record of every inmate and where they are placed,” the spokesperson said. “It’s just a constantly fluctuating figure so any figure quoted would be a misrepresentation of how many people are in segregated custody from day to day.”

Black cells vs segregation units

Brett Collins described ‘black cells’ as small, windowless cells that are totally sealed off once the door has been locked shut.”You can’t even see your hand in front of your face – all you see are glimmers of light under the door,” he said.

A spokesperson for Corrective Services New South Wales said no such ‘black cells’ exist today.

Collins says the other types of segregation cells he spent time in had lighting. He estimates these cells were around 1.8 metres wide – long enough to walk three paces – and he was permitted out of his cell for about six hours per day, though he rarely saw any other inmates.

Segregation units vary between correctional centres across Australia; some have their own exercise yard attached to the cell, while others have access to common exercise yards.

The fluctuating figure is dependent, the spokesperson says, on how many inmates have been involved in serious incidents, such as assaults on other inmates or staff, possession of contraband, and inmates who pose a continuous threat to other inmates or staff.

The Northern Territory and West Australian corrective services departments both cited similar reasons for being unable to provide an accurate figure: it would require extensive analysis of prison records, and a state- or territory-wide figure could not be produced at the present time.

In South Australia, what was commonly referred to as solitary confinement is now known as ‘separation’. A spokesperson for the SA Department for Correctional Services says there are currently 31 prisoners separated pursuant to the Correctional Services Act 1982.

Victoria’s prison population is approximately 6,300 and about 160 of these prisoners are in high-security or management units. A spokesperson for Corrections Victoria says prisoners in these units are assessed and reviewed frequently, and are subject to a higher degree of oversight than other members of the prison population.

In Queensland, there are 29 prisoners segregated on maximum-security orders as of October 7, 2014. Queensland has 38 commissioned cells in maximum-security units.

The Tasmania Prison Service (TPS) says it does not support a policy of solitary confinement, which implies complete isolation from others.

“The TPS separation policy aims to address the behaviours that led to a prisoner being separated and to return the prisoner to a mainstream regime as quickly as possible,” a spokesperson said. “And although direct physical contact is restricted, prisoners on a separation regime have natural light and ventilation, have their health and wellbeing monitored, access to open-air exercise, personal and professional visits, telephone calls, are able to communicate with others in the unit and have access to radios, reading, writing and educational materials.”

As of October 7, in Tasmania there are four prisoners subject to short-term disciplinary separation and another four subject to administrative segregation.

Life beyond bars for Brett Collins

Brett Collins was released from jail in June 1980 and immediately began working for the Prisoners Action Group in Sydney. He remains a prisoners’ rights advocate, currently working as a coordinator for Justice Action, a Sydney-based community-based prisoner rights advocacy group.

Collins’ first marriage ended six years into his sentence but he remains close to his son from that relationship. Collins remarried following his release, and also had two more children in another subsequent relationship. All three relationships ended; Collins has conceded this high personal cost was the result of his obsession with prison politics.

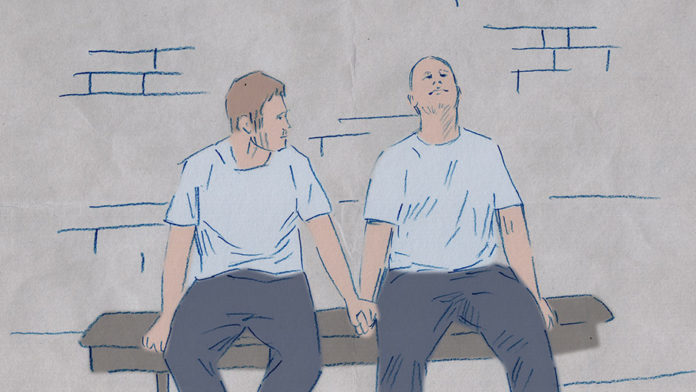

Collins says he found hope towards the end of his jail term when he fell in love with another man. After his release, he never saw the man again.

This article was published as part of the ABC’s Mental As initiative.