Mohammed Dorley, 33, desperately scanned the names scrawled on a piece of paper outside of the Island Clinic in Monrovia, Liberia. He was anxious to learn the fate of his 14-year-old daughter who had been admitted a week earlier, the LA Times reported.

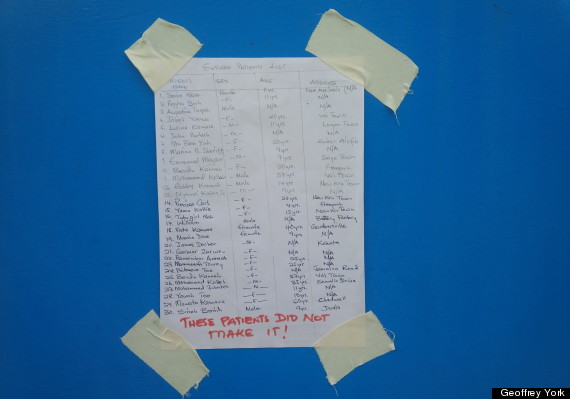

He reached the bottom of the lengthy list that concluded in bright red marker, “These patients did not make it!” without coming across his child’s name. In all likelihood, the concerned dad could breathe a sigh of relief.

In a country that has been ravaged by the worst Ebola outbreak in history, this is often how fearful parents find out if their kids have died from a disease that has claimed more than 3,000 lives and counting. They finger a handwritten sign and hope for the best.

Geoffrey York, the Globe and Mail’s Africa Bureau chief, snapped a photo of one of these “Expired Patients Lists” at the Island Clinic while on assignment and shared it on Twitter on Tuesday.

It was likely posted in a public place to “reassure any anxious family members who might have worried that their relatives had died,” York told HuffPost in an email. “If their name was not on this list, it implied that their relatives were still alive.”

The stark image puts into perspective what the overwhelming figures coming out of West Africa can’t.

Infected patients are isolated entirely and brandished with the shame that’s just one of the symptoms of the disease. In Liberia, the sick are relegated behind an orange double fence, where few ever emerge, considering that the virus has a 90 percent mortality rate, according to the Guardian.

It’s a fate that’s particularly difficult for communities in West Africa to accept, considering their wariness of doctors and their tradition of looking to the mothers for care when children fall ill.

But they don’t have a choice.

In Dorley’s case, he was only kept abreast of his daughter’s well-being by a handwritten note taped outside the hospital’s walls.

The sparse amount of information on the “expired” lists underscores just how many pressing questions go unanswered after a relative dies from Ebola.

Masa Alieu, 15, for example, knows little about the final days of her parents who died from the virus in Sierra Leone. She doesn’t even know where they are buried, Bloomberg reported.

“We did not see them when they died,” she told Bloomberg. “All I know is that people who die of Ebola are buried in bags.”