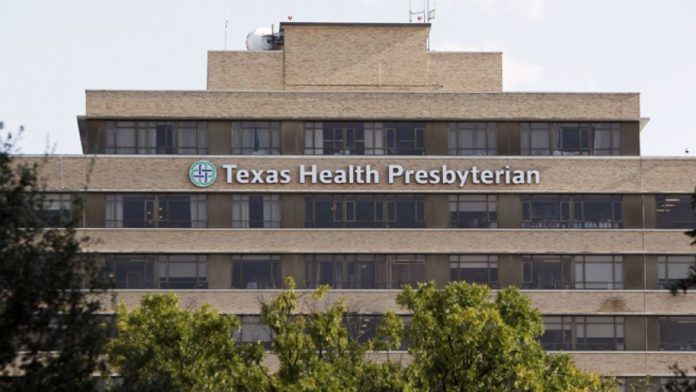

Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, pictured above, has come under scrutiny after sending home a patient who, several days later, tested positive for the Ebola virus. Still, U.S. health officials say the case poses a low risk to the general public.

The first patient ever to be diagnosed with Ebola in the US told medical staff that he had recently traveled from West Africa, but was not admitted to the hospital until he returned two days later, a hospital official said.

The patient, identified as Thomas Eric Duncan, told a nurse at a Dallas emergency room that he had recently visited Liberia, which has been ravaged by the Ebola outbreak. But an executive at Texas Health Presbyterian hospital told a news conference that the information was not widely enough shared with the medical team treating Duncan, and he was diagnosed as suffering from a “low-grade common viral disease.”

Edward Goodman, the infectious disease specialist at Texas Health Presbyterian hospital, told NPR that the patient’s symptoms were not definitive when he was first seen. “He was evaluated for his illness, which was very nondescript,” Goodman said. “He had some laboratory tests, which were not very impressive, and he was dismissed with some antibiotics.”

Duncan was sent home with a course of antibiotics, an outcome that hospital administrators described as “regretful.” On Sunday, four days after his symptoms began, Duncan was admitted to an isolation unit at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital – the same hospital that had sent him home just two days before. According to one report, Duncan was seen “throwing up all over the place” outside an apartment complex on Sunday before he was loaded into an ambulance and taken to the hospital.

A general view of The Ivy Apartments in Dallas, Texas, where Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan was picked up by ambulance on Sunday.

Health officials announced on Tuesday that tests confirmed the man, who had traveled from Liberia, was infected with the Ebola virus. Dr. Thomas Frieden, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said the patient was being treated in strict isolation and that all measures would be taken to ensure that the disease would not spread in the US.

“I have no doubt that we will control this case of Ebola so that it does not spread widely in this country,” he told a news conference. The disease has spread rapidly in West Africa, killing more than 3,000 people since March and continuing to pick up speed.

Failure to communicate

While experts agree that the US healthcare system is well prepared to contain the virus and prevent widespread transmission, many are raising questions about why the patient was not isolated immediately when he first arrived at the Texas hospital on Friday.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has helped lead the international response to Ebola, advises that all medical facilities should ask patients with symptoms consistent with Ebola for their travel history. Those who have recently traveled to Ebola-affected regions of West Africa should be treated “as if they have the disease,” Dr. Frieden said on Tuesday. While Duncan’s travel history was made known to medical staff, it “was not acted upon in an appropriate way,” Dr. Sanjay Gupta told CNN. “A nurse did ask the question, and he did respond that he was in Liberia, and that wasn’t transmitted to people who were in charge of his care,” he said. “There’s no excuse for this.”

“A travel history was taken, but it wasn’t communicated to the people who were making the decision. … It was a mistake. They dropped the ball,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases told CNN. “You don’t want to pile on them, but hopefully this will never happen again.”

Only patients who are showing symptoms of or have died from Ebola can transmit the disease, and it can only be spread through direct contact with blood or other bodily fluids. The patient began developing symptoms, which can include high fever, muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea, as well as internal and external bleeding, on September 24. He sought treatment for the first time on September 26 but was not admitted to the hospital until two days later.

Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan was initially sent home from the hospital for two days, during which he came into contact with up to 100 people in the Dallas area.

Hospital officials have acknowledged that the patient’s travel history wasn’t “fully communicated” to doctors, but also said in a statement Wednesday that based on his symptoms, there was no reason to admit him when he first came to the emergency room last Thursday night. “At that time, the patient presented with low-grade fever and abdominal pain. His condition did not warrant admission. He also was not exhibiting symptoms specific to Ebola,” officials from Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas said.

“The hospital followed all suggested CDC protocols at that time. Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas’ staff is thoroughly trained in infection control procedures and protocols,” the hospital said. The man underwent basic blood tests, but not an Ebola screening, and was sent home with antibiotics (which raises a totally different set of questions – namely, why did they give him antibiotics for a viral infection?). Three days later, the man returned to the facility, where it was determined that he probably had Ebola. He was then isolated.

Specimens from the patient arrived at the CDC in Atlanta on Tuesday, where tests determined he was suffering from Ebola. A state-operated laboratory in Texas also concluded that the specimens tested positive for Ebola, Dr. Frieden said at a press conference on Tuesday evening. Dr. Frieden also said that testing for Ebola is “highly accurate”.

Eighty people under observation

In an interview with CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta, the CDC’s Dr. Frieden was asked repeatedly whether the patient should have been tested for Ebola during his first visit to the hospital. “We know that in busy emergency departments all over the country, people may not ask travel histories. I don’t know if that was done here,” Dr. Frieden said. “But we need to make sure that it is done going forward.” Health officials are still looking at details about how the case was handled, he added.

Months after the WHO declared the Ebola outbreak an “international public health emergency,” experts are questioning how hospital administrators missed the warning signs when Duncan first came to the emergency room.

Dr. Frieden acknowledged that other people who came into contact with the patient could develop the disease. “It is certainly possible that someone who had contact with this individual … could develop Ebola in the coming weeks,” he said. More than a half a dozen CDC employees arrived in Dallas after news of the diagnosis broke. The CDC and Dallas County are working together in what they call a contact investigation. Anyone who had contact with the patient, including emergency room staff, will be under health officials’ observation for 21 days. If any of those being monitored show symptoms, they’ll be placed in isolation.

At this point, up to 100 people – including 5 children – are under observation, while Duncan’s immediate family members have been ordered to stay at home. The three paramedics who transported the patient in Dallas are temporarily off duty and among those under observation; they have tested negative for the virus and are also being restricted to their homes. Dr. Frieden said there was “zero risk” that the patient could have transmitted the disease on the flight from Liberia to the US, because he was not infectious at the time, while health officials in Texas reported that they do not have any other suspected cases in the state at this time but are closely monitoring the situation.

“Dallas County residents should be aware that the public health is our number one priority,” said Zachary Thompson, director of the Dallas County Department of Health and Human Services. “Our staff will continue to work hard to protect the health and welfare of the citizens in Dallas county.”

Responding to Ebola in the U.S.

The Texas patient is the fifth to receive treatment for Ebola in the US. Aid workers Dr. Kent Brantly of Texas and Nancy Writebol of North Carolina were the first Ebola patients to be treated in the US. Brantly and Writebol were treated in a bio-containment unit at Emory University hospital in Atlanta after contracting the virus in Liberia. They both recovered after receiving doses of an experimental drug called ZMapp, which has since been depleted. Brantly recently testified before Congress, imploring the international community to step up its response to the outbreak.

The experimental drug ZMapp looks to be a promising treatment for Ebola – it has shown encouraging results in animal studies and was used successfully in two patients, but two others who received the drug died. Available supplies of ZMapp have already been used up and it could take months to make more.

Dr. Rick Sacra, the third US aid worker to contract Ebola while working at a hospital in Monrovia, was released from Nebraska medical center last week. Sacra had gone back to Monrovia to work with obstetrics patients after fellow missionaries Brantly and Writebol were diagnosed. Meanwhile, a fourth patient is being treated at Emory. The patient’s identity has not been disclosed for confidentiality reasons, but he is believed to be a World Health Organization doctor who was treating Ebola patients in Sierra Leone. A fifth American, a civil servant with dual American-Liberian citizenship died in Monrovia in July.

The CDC has ramped up a national effort to stem the spread of Ebola, and in September President Barack Obama spoke at CDC headquarters in Atlanta. He called the virus a global health and security threat, and pledged U.S. assistance to the affected countries to try to stem the tide of the disease. After the Dallas diagnosis, the Obama administration is recirculating its guidance about how to respond to the virus, White House spokesman Josh Earnes said at a press conference.

Dr. William Schaffner, the chairman of the department of preventive medicine and professor of infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee, and the past-president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, told weather.com Americans should not fear the disease.

“We see the risk as essentially zero,” he said. He explained that he thinks the American public fears Ebola because its strange, mysterious and serious, but emphasizes that it’s far less of a threat to the average person than, say, the seasonal flu, which kills more than 35,000 Americans every year. “If someone is returning from Sierra Leone, and has Ebola, but is not yet sick, I could sit right next to them on a plane and not be concerned,” Dr. Schaffner said.