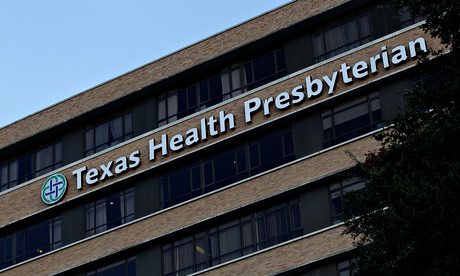

As the first case of Ebola diagnosed in the US sends shockwaves through healthcare systems across every state, questions will be asked as to why the man, who flew in from Liberia on 20 September, was not tested and isolated as soon as he presented at the Texas Health Presbyterian hospital in Dallas six days later.

Instead, he was allowed home, where his condition grew rapidly worse and he was eventually transferred by ambulance on Sunday.

The first symptoms of Ebola are very similar to those of colds and flu, so the man may have arrived with no more than a fever. No details of the patient have been released, but the absence of suspicion on the part of medical staff suggests he may not be from west Africa and did not tell them that he had recently been there.

Public health experts involved in the battle to control the epidemic raging in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia say the biggest problem is that people are not diagnosed until too late, when they have spread the infection, often to many other people. The Dallas case shows how easily that can happen when the index of suspicion is low.

If any hospital in the US had been complacent about Ebola, they will not be so now. The unnamed patient became a greater risk to those around him the longer he was out in the community. People with Ebola are not infectious until symptoms develop. As time goes on, and they sweat, vomit and lose control of their bodily functions, they become more and more infectious. The virus is spread in body fluids and any surfaces contaminated by them.

The Dallas patient will have posed less of a risk to other people when he first turned up at hospital and was sent home than two days later, when the ambulance was summoned. The paramedics who transported him will now be closely monitored for symptoms and the ambulance itself will have to be decontaminated.

The man showed no symptoms on his flight from west Africa and will not have infected anybody else during it, according to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), which confirmed the Ebola case after laboratory testing. Public health officials will have already embarked on tracing every contact since he arrived on US soil, and particularly those over the last few days.

Every contact will be asked to stay at home and health workers will monitor them. They will be asked to report any signs of fever or other illness.

Those in the house where the man was staying and who may have helped nurse him are at greatest risk. It is not possible to contract Ebola without physical contact with somebody who has it or surfaces they have touched, including cutlery and the lavatory. The virus can incubate for up to 21 days without causing symptoms. Paramedics taking extreme precautions, including the use of protective suits, will take anyone who becomes ill to an isolation unit.

Contact tracing, carried out promptly and efficiently, can and does bring epidemics to a halt. That is how previous outbreaks of Ebola have been contained. Nigeria has just shown how well it can work, even in a very difficult situation in which the infection had been brought into a crowded city. The CDC said on Tuesday that Nigeria’s epidemic was probably over. It began when a US citizen, Patrick Sawyer, flew in to Lagos, became ill and died five days later. One of his contacts fled to Port Harcourt and sparked an outbreak there. Prompt action by Nigerian health officials, assisted by the CDC, led to the tracing of 900 contacts. There have been 20 probable cases and eight deaths. All but three of the contacts are now out of the incubation period and the rest will be clear on Thursday. Senegal has also kept out the epidemic after tracing and monitoring 67 contacts of the one person from Guinea who crossed its border with the disease.

The CDC points out that the US has successfully contained diseases similar to Ebola before. It has had five imported cases of haemorrhagic fever in the past – four of Lassa fever and one of Marburg. In all those cases, every contact was traced and no transmission of the virus occurred.

Not all hospitals in the US are prepared, however, the biggest nurses’ organisation claims. National Nurses United (NNU) surveyed registered nurses in a dozen states. More than 60% said their hospital was not prepared for Ebola and 80% said it had not communicated any policy on the admission of patients suspected of suffering from disease. More than a quarter said their hospital did not have enough protective equipment, such as eye masks and fluid-resistant gowns, and 85% said their hospital had not educated them on the disease.

At a rally in Las Vegas last week to protest about inadequate preparations in US hospitals, the NNU’s executive director, RoseAnn DeMoro, said a dramatic response was needed immediately. “When these patients come to your hospital, it’s not going to be the corporations or the people on Capitol Hill who are going to be there, it’s nurses, and unless we have adequate preparation, we’re putting people in harms way,” she said.

Professor Tom Solomon, the director of the UK’s health protection research unit in emerging infections based at the University of Liverpool said: “This is worrying news about the virus’ spread to America for the first time. But in fact work we have been doing at … the University of Liverpool predicted that America was one of the countries at greatest risk of importing the disease. This was based on our knowledge of airline passenger travel.

“Although it is worrying that Ebola has spread beyond Africa in this way, the chances of it becoming established in America or other western countries is very small. This is because unlike the affected countries in western Africa, we have well established systems in place which can contain such a disease.”