Normally it takes years for scientists to establish that a new vaccine is both safe and effective for use in the field. But with hundreds of people dying each day in the worst ever outbreak of Ebola, there is no time to wait, experts say.

In an effort to save lives, health authorities are determined to roll out potential vaccines within months, skipping over some of the usual testing, and raising unprecedented ethical and practical questions.

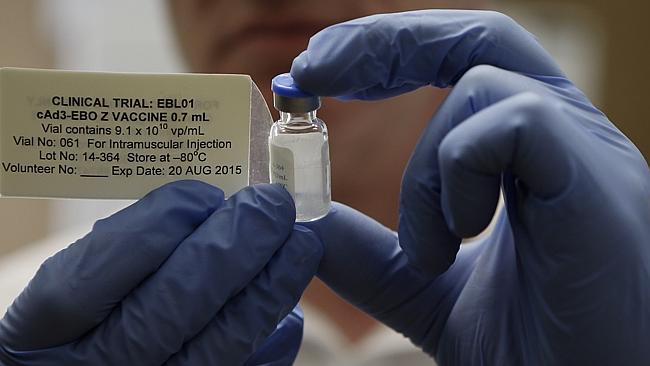

“Nobody knows yet how we will do it. There are lots of tough real-world deployment issues and nobody has the full answers yet,” Adrian Hill, who is conducting safety trials on healthy volunteers of an experimental Ebola shot developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), told Reuters. If his results show no adverse side-effects, GSK’s new shot could be given to people in West Africa by the end of this year, Hill said.

Even if a drug is shown to be safe, it takes longer to establish that it is effective – time that is simply not available when cases of Ebola infection are doubling every few weeks and projected to reach into the hundreds of thousands in the next several months.

Among the questions that scientists are grappling with are, Should an unproven vaccine be given to everybody, or just a few? Should it be offered to healthcare workers first? The young before the old? Should it be used first in Liberia where Ebola is spreading fastest, or Guinea where it is closer to being under control?

And should people be told to assume it will protect them from Ebola? Or should they take all the protective measures they would if they hadn’t been vaccinated? And if so, how will anyone know whether the vaccine works?

GSK is among several drug firms that have either started or announced plans to start human trials of candidate Ebola vaccines. Other companies include Johnson & Johnson, NewLink, Inovio Pharmaceuticals and Profectus Biosciences. The World Health Organization says it hopes to see small-scale use of the first experimental Ebola vaccines in the West Africa outbreak by January. The agency has convened vaccine specialists, epidemiologists, pharmaceutical companies and ethicists, for a meeting on Monday and Tuesday to discuss the moral and practical issues.

Under normal circumstances, “safety is the absolutely paramount thing when you’re developing a new vaccine,” said Brian Greenwood, a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who will take part in the WHO-led meeting. “[B]ut this time we’re going to have to take more risks.”

“Quite how we do that, and what risks we take, hasn’t really been thought through yet. That’s what people are trying to figure out,” he added.

An ethical gray area

The chaos caused by the epidemic itself greatly complicates the process of deploying and tracking use of a new vaccine. Working on an expedited timeline, scientists must simultaneously complete two phases of testing that are usually carried out separately and in a tightly controlled environment. “You’re trying to do two things at the same time: you’re trying to evaluate a vaccine and deploy it – when normally you would evaluate the vaccine first, by doing a randomized double blind controlled trial, and then you’d deploy it if it was shown to be safe and effective,” Hill said.

Because Ebola virus is so deadly, those who receive a trial vaccine must be advised to take all other precautions and protect themselves fully from coming into contact with the virus. This could make it harder for researchers to determine whether the protective clothing and other safety protocols, or the new vaccine, is what conferred protection from the pathogen.

Traditionally, efficacy trials randomly assign participants to receive the vaccine or a placebo (dummy) shot. That’s clearly not ethical here, so some researchers are calling for a “step-wedge” trial, which analyzes what happens to people at similar risk who receive the vaccine at different times. That way those who have been vaccinated can be compared with others who have yet to receive their shots.

It is possible that limited supplies of any candidate vaccine could result in a type of natural control group being formed anyway. If that happens, researchers could compare populations where the vaccine is available with those where it isn’t. However, that is still a far cry from the controlled settings of most clinical trials, making it impossible to decipher whether any observed effects were caused by the experimental vaccine, or if they were actually driven by other differences between those who received the vaccine and those who didn’t. For instance, the rate of spread can differ between sites because one might have, say, better or worse personal protection measures, which could cloud analyses of a vaccine’s shortcomings or strengths.

GSK has committed to manufacturing up to 10,000 doses of the vaccine, which consists of an Ebola surface protein stitched into a weakened chimpanzee adenovirus, by the end of the year. If it passes muster in the early studies, it could be given to health workers as soon as November. But hundreds of thousands of doses would be needed to put a dent in the outbreak — and that could take a year or longer, said Ripley Ballou, who heads the Ebola vaccine program for GSK.

NewLink Genetics of Ames, Iowa, has a second vaccine in a phase I trial that consists of a crippled vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), which infects livestock, with the gene for the Ebola virus surface protein. Only 1500 doses exist. Profectus makes a similar vaccine that should be ready for human testing next June.

Most experts agree that the first doses of any vaccine should go to healthcare workers on the frontline, since their risk of exposure is so high. Researchers could then compare infection rates among health workers who receive the vaccine to those working in regions still waiting for it. Determining how to prioritize vaccination among the general public is much more controversial, plunging scientists headfirst into uncharted ethical territory. Among the most troubling questions that must be answered is, if a drug or vaccine turns out to be harmful, have we unethically experimented on a vulnerable population?

While the ethics of the situation are undoubtedly complicated, it will likely take such an unprecedented response to combat this unprecedented outbreak, which the United Nations recently said was the greatest peacetime challenge they’ve ever faced. Reverting to the traditional years-long process of testing vaccines, and withholding them from West Africa until then, is not an option, experts say.

“I don’t believe that our traditional methods of being able to control and stop outbreaks … is going to be effective,” said Dr. Daniel Lucey, an expert on viral outbreaks and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University Medical Center, who recently spent three weeks in Sierra Leone, one of the countries affected by the devastating Ebola outbreak.

Without vaccines or drug treatments for Ebola, “I’m not confident we will be able to stop it,” Dr. Lucey said.