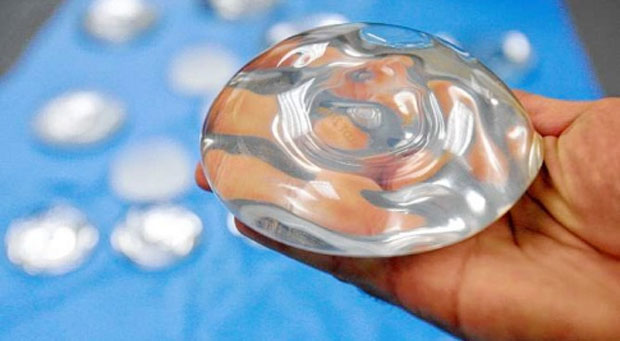

Breast augmentation was the most commonly performed cosmetic surgical procedure in the US last year, with around 290,000 women receiving either silicone or saline breast implants. Although extremely rare, some patients who have had this procedure develop a blood cancer called anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Now, a new study has shed light on why this is.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), responsible for around 3 percent of NHLs. ALCL typically appears in the skin, lymph nodes, liver and soft tissue.

On rare occasions, however, the cancer has appeared in the breast, and according to this latest research – led by Dr. Suzanne Turner of the University of Cambridge in the UK – almost all cases of breast ALCL have occurred in patients who have had breast augmentation, with the tumors always developing in the scar tissue surrounding the implant.

For their study, published in the journal Mutation Research, Dr. Turner and colleagues conducted a review of all available studies looking at ALCL, as well as patient case reports.

There have been 71 known ALCL cases worldwide that the researchers say are linked to the patient’s breast implants. This shows that implant-related ALCL is extremely rare, affecting around 1-6 women in every 3 million who undergo breast augmentation.

But just because it is rare does not mean its underlying mechanisms should not be investigated, according to Dr. Matt Kaiser, head of research at Leukemia and Lymphoma Research in the UK – a blood cancer charity that funded the study:

It is important to investigate any possible links to what causes these cancers, so that we can help people balance benefits versus risks and so that we can work out how we might be able to prevent the risks altogether.

Breast implants ‘may trigger abnormal immune response, causing cancer’

Patients with ALCL are usually divided into two groups: those whose cancer cells possess an abnormal surface protein called anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and those whose cancer cells do not have ALK.

Patients with ALK-positive ALCL usually respond well to treatment and the majority survive 5 years or more, while those who are ALK-negative often require more aggressive treatment, with only around 50 percent surviving over 5 years.

However, Dr. Turner and her team found that nearly all patients included in their analysis with breast implant-related ALCL were ALK-negative, with most of them responding well to treatment. They note that of the 49 cases in which they had access to patients’ treatment progress, only five deaths were reported.

Furthermore, they found that for many of these women, their cancer was successfully treated simply by removing their breast implant and the tissue surrounding it rather than undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy, indicating that the breast implant may trigger an abnormal immune response in the body, causing cancer.

These findings, the researchers say, provide clues to the underlying cause of breast implant-related ALCL and may pave the way for better treatment strategies specific to this disease.

“It’s becoming clear that implant-related ALCL is a distinct clinical entity in itself,” Dr. Turner says. “There are still unanswered questions and only by getting to the bottom of this very rare disease will we be able to find alternative ways to treat it.”

This is not the first time breast implants have been linked with serious health complications. In a study published last year, researchers discovered that Poly Implant Prothese (PIP) breast implants have a high number of small molecules known as D4, a type of endocrine disrupting chemical (EDC) that can harm a developing fetus.

PIP breast implants have also been pegged in the development of suspicious cases of cancer, leading medical authorities in some countries to tell women with PIP implants that they should have them removed.