A physician and infectious disease specialist who just returned from treating Ebola patients in West Africa has delivered a sobering statement, predicting that the current Ebola outbreak will go on for more than a year, and will continue to spread unless a vaccine or other drugs that prevent or treat the disease are developed.

Dr. Daniel Lucey, an expert on viral outbreaks and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University Medical Center, recently spent three weeks in Sierra Leone, one of the countries affected by the devastating Ebola outbreak. While there, Dr. Lucey evaluated and treated Ebola patients, and trained other doctors and nurses on how to use protective equipment.

The current Ebola outbreak, which has primarily affected Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, has killed at least 1,552 of the more than 3,000 people infected, making it the largest and deadliest Ebola outbreak in history. It is also the first outbreak to spread from rural areas to cities, and it’s the first time Ebola has ever made it to West Africa. Infection control strategies that have worked in the past to stop Ebola outbreaks in rural areas may not, by themselves, be enough to halt this outbreak, Dr. Lucey said.

“I don’t believe that our traditional methods of being able to control and stop outbreaks in rural areas … is going to be effective in most of the cities,” Dr. Lucey said last week in a talk held at Georgetown University Law Center that was streamed online. While the World Health Organization (WHO) has released a “road map” to stop Ebola transmission within six to nine months, “I think that this outbreak is going to go on even longer than a year,” Dr. Lucey warned.

In addition, without vaccines or effective treatments for Ebola, “I’m not confident we will be able to stop it,” Dr. Lucey said. There are a few studies of Ebola treatments and prevention methods under way, but more research is needed to show whether they are safe and effective against the disease.

Experts say several key factors are contributing to the continued spread of the virus. Among the most pressing concerns are a lack of basic protective equipment and medical supplies, cultural barriers and public misconceptions, and — most importantly — increased global cooperation, including the establishment of an international fund to prepare for future outbreaks.

Lack of personal protective gear, medical supplies

One strategy that could help with the current outbreak is to implement public health “command centers” whose job it is to make sure that tools and equipment sent to the affected regions are properly distributed to places that need them, Dr. Lucey said.

When Dr. Lucey was in Sierra Leone, protective equipment for health care workers made its way to the capital city, but not to the hospital where he was working, he said. “We did not have gloves that I felt safe with,” Dr. Lucey said, noting that the gloves would tear easily. “We didn’t have face shields. We had goggles that had been washed so many times you couldn’t see through them,” he said.

In fact, the scarcity of personal protective equipment is cited as one of two primary factors driving transmission of the virus among health care workers. The other factor, say infectious disease specialists David G. Fairchild, MD, MPH, and Lorenzo Di Francesco, MD, FACP, FHM, is that even when such gear is available, it is very easy to make a mistake in the conditions the health care teams are working in — usually in tents set up outdoors, in the heat of Western Africa, often for 12 hours at a time due to limited staff.

These shortcomings existed long before the Ebola outbreak. Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone — the most severely affected countries — have only recently returned to political stability following years of civil war and conflict, which left health systems largely destroyed or severely disabled. According to one study, which was published in August but conducted last spring, only 56 percent of hospitals in Liberia had protective eyewear for doctors and nurses and only 63 percent had sterile gloves. In Sierra Leone, those figures were 30 percent and 70 percent, respectively, the researchers found.

Ensuring that health care workers have adequate protective gear is particularly important given the devastating impact the virus has had on the medical community: Of the more than 2,000 who have already died in West Africa, about 10 percent are health workers, an “unprecedented” infection rate, says the WHO. “Health workers on the frontline are becoming infected and are dying in shocking numbers,” noted Dr. Joanne Liu, president of Doctors Without Borders.

Overcoming cultural barriers

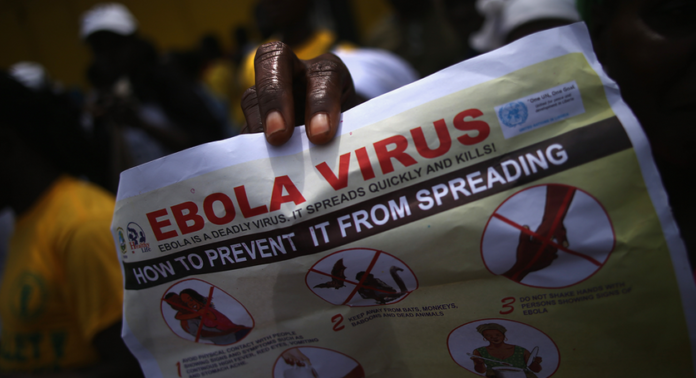

Another important factor in controlling the outbreak will be community engagement and education to help people in the region understand the behaviors that spread the disease, said Dr. Marty Cetron, director of Global Migration and Quarantine at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Local populations are often resistant to aid workers and outbreak control measures and are often reluctant to practice good burial methods, performing ritual washing of infected corpses that have been shown to carry heavy viral loads even on the skin, Cetron said.

“There is political unrest. There is a dissatisfaction and distrust of government, as well as of the people coming in to assist in this outbreak,” said Dr. Aileen Marty, who spent 25 years serving as a Navy doctor specializing in tropical medicine, infectious disease pathology and disaster medicine, and is now in West Africa working with a WHO outbreak alert and response team. “Some aid workers have been attacked by people in the plagued area who believe the outsiders are spreading the virus. Some are in denial of ill family members, and are relying on ‘witchcraft’ to help those who are sick.”

There are now wide swaths of land called ‘shadow zones‘, where health care workers cannot and will not go. As a result, many cases are going undocumented, likely masking the true scale of the outbreak, says the WHO. “Fear is proving to be the most difficult barrier to overcome,” the WHO reports.

Understanding the culture of an area so that control strategies are culturally acceptable will be key to bringing the outbreak under control, Cetron said.

Inadequate global response

This large Ebola outbreak could have been prevented with an effective public health response at the beginning, said Lawrence Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University. But the weak health systems of the affected countries left them unprepared to respond to the outbreak, Gostin said. He also said the international community had not responded adequately to the crisis.

Others have been far more critical of the global response: In a recent article in the Washington Post titled, “The world yawns as Ebola takes hold in West Africa,” Dr. Richard E. Besser, chief health editor of ABC news and former acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said bluntly: “I don’t think the world is getting the message.” He goes on:

The level of response to the Ebola outbreak is totally inadequate. At the CDC, we learned that a military-style response during a major health crisis saves lives…

We need to establish large field hospitals staffed by Americans to treat the sick. We need to implement infection-control practices to save the lives of health-care providers. We need to staff burial teams to curb disease transmission at funerals. We need to implement systems to detect new flare-ups that can be quickly extinguished. A few thousand U.S. troops could provide the support that is so desperately needed.

Aid ought to be provided on humanitarian grounds alone, he argues — but if that isn’t adequate rationale, he adds that aid offered now could protect us in the West from the non-medical effects of Ebola’s continuing to spread: “Epidemics destabilize governments, and many governments in West Africa have a very short history of stability. U.S. aid would improve global security.”

Similarly, Gostin called for the establishment of an international health systems fund, which would be supported by high-resource countries. The money would be used to strengthen the health systems in those countries, he said.

“A dedicated International Health Systems Fund at WHO would rebuild broken trust, with the returns of longer, healthier lives and economic development far exceeding the costs,” Gostin wrote in a commentary in the journal The Lancet. “This fund would encompass both emergency response capabilities and enduring health-system development.”

“It is in all states’ interests to contain health hazards that may eventually travel to their shores,” Gostin wrote. “But beyond self-interest are the imperatives of health and social justice—a humanitarian response that would work, now and for the future.”