One of the more puzzling aspects of the current debate over health funding is the lack of new or innovative policy options being proposed by the Government and others from the conservative side of politics. Given the level of panic being invoked about our alleged health funding crisis (disputed by many economists) it would seem logical that policy makers should be searching for viable options to combat the so-called health spending tsunami.

One of the more puzzling aspects of the current debate over health funding is the lack of new or innovative policy options being proposed by the Government and others from the conservative side of politics. Given the level of panic being invoked about our alleged health funding crisis (disputed by many economists) it would seem logical that policy makers should be searching for viable options to combat the so-called health spending tsunami.

Yet apart from the GP co-payment, there are few, if any, realistic policy options being put on the table for discussion. The co-payment proposal has clearly not been accepted by either consumers or health care providers (for good reasons, as discussed at length here and here). But since the failure of the Government to convince stakeholders that increased primary care co-payments are the way forward, there has been no ‘Plan B’ on offer to reform health funding arrangements to meet the changing needs of the community.

The only contribution to the debate from the right thus far has been a proposal for individual health savings accounts (based on the Singapore model) from David Gadiel and Jeremy Sammut at the Centre for Independent Studies. This option reflects the Government’s aim of encouraging consumers to contribute more in direct funding to their health care but would be a radical change to our current system and unlikely to gain the support of the current Senate. Health savings accounts have also been criticised by a number of experts for widening existing inequities in access to health care and increasing overall costs.

However, even without radical reform there are options for changing our current health funding arrangements to address some of the problems inherent in the system and to support greater choice and flexibility for consumers in the way they access and pay for their health care. The following three policy options are ones that I presented recently at the Catholic Health Australia conference in Brisbane as part of a broader presentation on health funding.

None of these options are without their limitations or implementation challenges, but all would provide greater support for consumers to pay for private health care without the equity or inefficiency problems inherent in the co-payment proposal and without requiring major structural changes to our current funding system.

Whether or not the claims of a ‘health funding crisis’ are justified, it’s never a bad time to discuss how our financing system can be improved to reflect consumers’ needs. Rather than continually flogging the dead horse of GP co-payments, the Government should be looking forward and engaging consumers and other stakeholders in a debate over alternative funding reforms, such as the following:

- The Health credit card

The proposal (in brief)

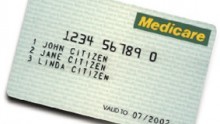

Every person is issued with a ‘health credit card’ with which they use to pay for all health services, including those subsidised by both public and private insurance.

The Government takes over the payment function for all health services, paying providers directly on a monthly basis, and collecting relevant rebates and subsidies from private health insurance, state governments and other sources.

The Government subtracts relevant rebates and subsidies from the total cost of services and sends consumers a bill for the net amount each month.

Consumers can either pay the outstanding amount in full each month or pay it off over a longer period of time in instalments, at a low interest rate (similar to a credit card).

Consumers whose ‘health debt’ exceeds an agreed proportion of their income (e.g. 5%) could pay off their outstanding amount over time through regular payments linked to their income (similar to HECS).

The problems addressed

Out-of-pocket costs for health care are distributed very unevenly across the population and many people, in particular, those on low incomes and/or with chronic conditions struggle to afford their health care expenses.

Health care costs often occur unexpectedly and can coincide with periods of reduced earning capacity. Cost barriers to access can therefore be due more to a ‘cash flow’ problem than an overall ‘affordability problem’.

There is an inherent inefficiency for both providers and consumers in having to manage large volumes of small transactions for individual health care services.

Our current system of rebates and subsidies for health care requires consumers to undertake multiple different processes in order to pay for health care.

A health credit card would increase the efficiency of current health payments and give consumers more control over managing unexpected and large out-of-pocket costs.

- The private health insurance ‘opt-out’

The proposal (in brief)

Consumers would be able to ‘opt out’ of private health insurance and receive in lieu a payment equivalent to the rebate and tax subsidy.

This money could only be used to pay for all or part of the cost of private hospital treatment, allied and dental health services or other health-related products.

People with private health insurance and those who choose to ‘opt out’ would be given the lowest priority on public hospital waiting lists for elective procedures available in the private sector.

The problems addressed

Subsidies for private health insurance currently cost the community around $5.5 billion a year but this funding is not well targeted and many people with high health care needs miss out.

This is because private health insurance does not meet the needs of many consumers, including: those on low incomes who cannot not afford the premiums and/or the co-payments (required when using private services); people with chronic conditions requiring regular allied health care who find that annual limits are inadequate to meet their needs; people in rural areas where there are few private health services available; and people who use products and services not subsidised by private health insurance, such as GP services, non-prescription medicine and many medical devices.

Private health insurance subsidies aim to reduce pressure on the public hospital system and yet people with insurance can access public hospitals without penalty.

A more flexible subsidy arrangement such as this would support all consumers to access private health care in a way that meets their needs.

- The public hospital excess

The proposal (in brief)

Consumers would be able to nominate to pay an excess each time they accessed a public hospital and in return be provided with a subsidy for other forms of health care.

This would enable people to access lower cost preventive health care with the aim of avoiding or delaying hospital treatment.

Emergency admissions could be excluded and payments would be retrospective, ensuring that there are no cost barriers at the point of admission.

The problems addressed

Currently, public hospital care is free at the point of service but lower cost preventive care, such as GP services, dentistry and allied health care typically require out-of-pocket payments, often significant.

This creates cost barriers to accessing primary health care, with the result that many people delay or avoid treatment until they develop a more serious condition and require hospitalisation.

Allowing people to take on some of the risk of requiring public hospital treatment in return for greater access to primary health care would support people to prevent and manage their long-term health care and target spending where it will deliver greatest value.

Thanks to Catholic Health Australia for inviting me to their National Conference 2014. I haven’t been to many health conferences where the ‘between sessions’ conversations can include passionate advocacy for a more compassionate refugee policy, a robust debate on the economics of caring for an ageing community, an analysis of the impact of the 1829 Emancipation Act on modern Australian society and a discussion about the quirks of Aramaic syntax!