Researchers have traveled to the ends of the earth in search of exotic microorganisms that can produce the medicine we need to live and thrive. But as a new study points out, we may have overlooked an extremely rich source of drugs that was right under our noses: bacteria in and on the human body.

Scientists from University of California, San Francisco School of Pharmacy have pinpointed a vaginal bacterium that naturally plays a role in the organ’s defense, isolated and amplified its defense capabilities, and created an antibiotic that can kill harmful pathogens while sparing the bacteria that are an important part of the vagina’s bacterial environment.

“We used to think that drugs were discovered by drug companies and approved by the FDA and then prescribed by a physician, and then they get to you,” lead researcher and biologist Michael Fischbach, Ph.D. told The Huffington Post. “What this finding shows is that bacteria that live on and inside of us are mounting an end run around the process.”

The vaginal bacterium Lactobacillus gasseri was the basis of an antibiotic called lactocillin that can kill the pathogens that cause vaginal infections, but without wiping out the bacteria that coexist peacefully with the organ. Traditional antibiotics can have a scorched earth effect, wiping out all bacteria — even the good kinds — which can lead to more problems down the road.

But beyond the immediate implication (a possible new drug for vaginal infections), the methods used to find the bacteria could upend the way we approach pharmaceutical research and manufacturing, argues Fischbach.

A microbiome of over 100 trillion bacteria lives on and in each one of us, and most of them are either benign or even helpful. Fischbach’s research is some of the first to search for drug-producing bacteria within the human microbiome.

“It’s very early days and we don’t know all the implications yet, but it looks like gut, skin and oral bacteria are better chemists than we thought, and are capable of making many more molecules that resemble drugs than had previously been realized,” said Fischbach. “This may be a great way of learning just how helpful bacteria help us.”

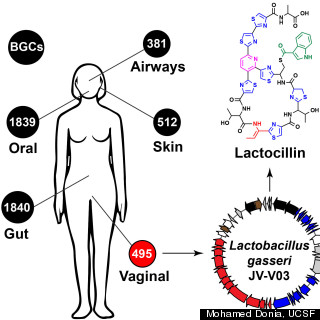

Fischbach’s team identified more than 3,000 clusters of bacterial genes on humans that can make drug-like molecules.

Fischbach’s team identified more than 3,000 clusters of bacterial genes on humans that can make drug-like molecules.

To isolate the Lactobacillus gasseri’s special drug-producing powers, Fischbach used a computer algorithm to look through the genome sequences of bacteria collected as part of the NIH Human Microbiome Project, an ongoing, multi-center effort to genetically map out the bacteria that live in the human body. He was looking to see if he could spot drug-producing genes that were especially common. Although Fischbach isolated bacteria from inside the vagina, he is hopeful that the technology could benefit men as well.

“We think they still have bacteria producing the same drug, but it’s just a different bacterial species that lives in the mouth and has not yet been isolated,” explained Fischbach.

The need for new antibiotics is urgent; it’s estimated that at least two million people in the U.S. become infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria, which results in 23,000 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The growing antibiotic-resistant threat is what makes Dr. Vincent Young, M.D., Ph.D., so excited about the implications of Fischbach’s research. As both an associate professor and an infectious disease physician at University of Michigan’s Medical School department of internal medicine, Young regularly encounters patients that show up at the hospital with multi-drug resistant infections.

“We almost have nothing to treat these patients,” said Young in a phone interview with the Huffington Post. “This is a new way of doing drug discovery.”

More broadly, Young called Fischbach’s study a “technical tour de force” that stands out among other papers on the microbiome for the way he used what was already known about our bacteria (their genetic sequences), turned it into a new medicine and then analyzed the way it interacted with the rest of the bacterial community in the vagina.

“It really points the way on how microbiome research will move in the future,” concluded Young.

Joseph Petrosino, Ph.D., director of the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome research at Baylor University, echoed Young’s praise for Fischbach’s methodology. Petrosino wasn’t involved with Fischbach’s research, but praised the study for providing insight on just how crucial our good bacteria is for overall health.

“This research demonstrates directly how the microbiome can convey protection against pathogens that are a constant threat to human health,” wrote Petrosino in an email to HuffPost.

The study was published in the Sept. 11, 2014 issue of the journal Cell.