(Reuters) – More than 800,000 people each year worldwide commit suicide – around one person every 40 seconds – with many using poisoning, hanging or shooting to end their own lives, the World Health Organization (WHO) said on Thursday.

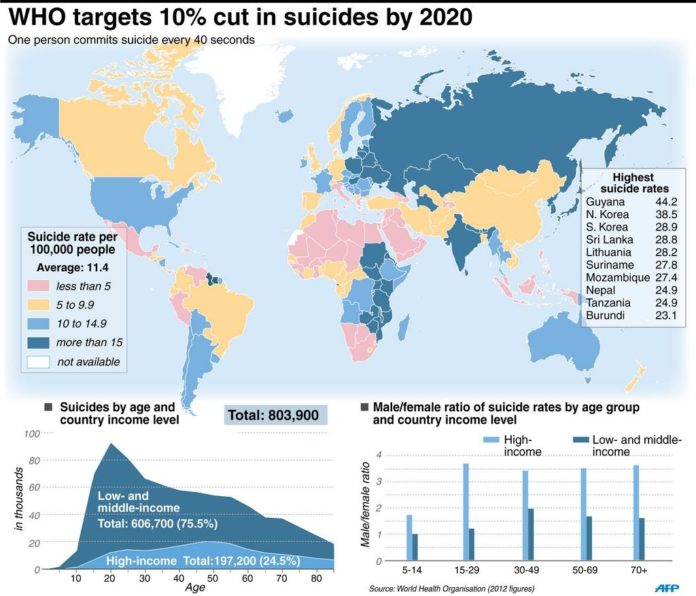

In its first global report on suicide prevention, the United Nations health agency said some 75 percent of suicides are among people from poor or middle-income countries and called for more to be done to reduce access to common means of suicide.

The report found that suicides take place all over the world and at almost any age. Globally, suicide rates are highest in people aged 70 and over, but in some countries, the highest rates are found among the young.

In the 15 to 29-year age group, suicide is the second leading cause of death globally.

The WHO’s director general Margaret Chan said the report was a “call for action to address a large public health problem which has been shrouded in taboo for far too long.”

Pesticide poisoning, hanging and firearms are among the most common methods of suicide globally, the report said, and evidence from Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, the United States and Europe shows that restricting access to these means can help to stop people from committing suicide.

Governments should also set up national prevention plans, the report said, noting that currently only 28 countries are known to have such strategies.

The report found that in general, more men die by suicide than women. In richer countries, three times as many men kill themselves as women, and men aged 50 and over are particularly vulnerable.

In poor and middle-income countries, young people and elderly women have higher rates of suicide than their counterparts in wealthy nations, the report found. And women over 70 are more than twice as likely to commit suicide than women aged between 15 and 29.

Some of the highest rates of suicide are found in central and eastern Europe and in Asia, with 25 per cent occurring in rich countries, the report says. Men are almost twice as likely as women to take their own lives.

“No matter where a country currently stands in suicide prevention, effective measures can be taken, even just starting at local level and on a small scale,” said Alexandra Fleischmann, a scientist at the WHO’s department of mental health and substance abuse.

Other preventative measures include encouraging responsible reporting of suicide in the media, such as avoiding language that sensationalizes suicide.

Early identification and management of people with mental illness and drug and other substance abusers is also important.

“Follow-up care by health workers through regular contact, including by phone or home visits, for people who have attempted suicide, together with provision of community support, are essential, because people who have already attempted suicide are at the greatest risk of trying again,” the report said.

The WHO report was published ahead of world suicide prevention day on September 10.

‘Don’t glamourise suicide’

Alexandra Fleischmann, one of the report’s co-authors, said part of the blame lies with the publicity given to suicides by famous people, such as Hollywood actor Robin Williams. The Oscar-winning star, who had suffered from depression, was found dead at his home on August 1, prompting an outpouring of emotion from the public and widespread media coverage.

Ella Arensman, president of the International Association for Suicide Prevention, said that after news broke of Williams’ death she received “five emails of people who had recovered (from a) suicide crisis and saying that they are thinking again about suicide”. “These overwhelming reports can have a contagion effect on vulnerable people,” she said, referring also to the “sharp increase” in suicides after German football player Robert Enke killed himself in 2009.

“Suicide should not be glamourised or sensationalised,” Fleischmann said, urging news outlets not to mention suicide as the cause of death at the start of reports, but only at the end, “with a mention of where (the reader) can find help”. WHO, which called suicide a major public health problem that must be confronted and stemmed, studied 172 countries to produce the report, which took a decade to research.

It said that in 2012, high-income countries had a slightly higher suicide rate – 12.7 per 100,000 people, versus 11.2 in low- and middle-income nations. But given the latter category’s far higher population, they accounted for three-quarters of the global total. Southeast Asia, including North Korea, India, Indonesia and Nepal, made up over a third of the annual figure.

WHO cautioned that suicide figures are often incomplete, with many countries failing to keep proper tallies. In addition, “there are many suicide attempts for each death,” WHO chief Margaret Chan said. “The impact on families, friends and communities is devastating and far-reaching, even long after persons dear to them have taken their own lives,” she added.

‘Suicides are preventable’

Suicide and attempted suicide are considered a crime in 25 countries, mostly in Africa, in South America and in Asia. The most suicide-prone countries were Guyana (44.2 per 100,000), followed by North and South Korea (38.5 and 28.9 respectively).

Next came Sri Lanka (28.8), Lithuania (28.2), Suriname (27.8), Mozambique (27.4), Nepal and Tanzania (24.9 each), Burundi (23.1), India (21.1), and South Sudan (19.8). Next were Russia and Uganda (both with 19.5), Hungary (19.1), Japan (18.5), and Belarus (18.3).

The UN agency said its goal is to cut national suicide rates by 10 per cent by 2020. A major challenge, it said, is that suicide victims are often from marginalised groups of the population, many of them poor and vulnerable. However, “suicides are preventable”, Chan said.