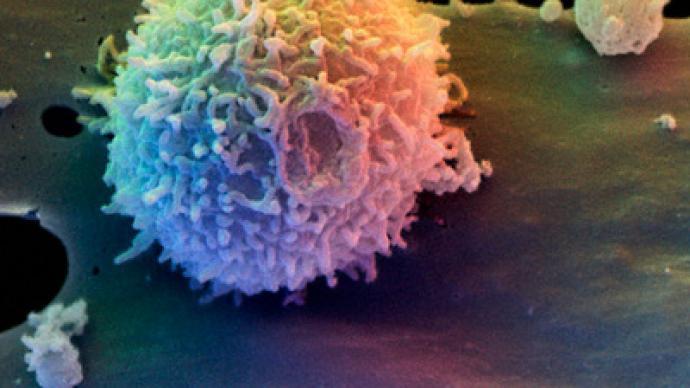

A new study sheds light on the body’s initial response to infection with the HIV virus. The findings could potentially lead to new treatment approaches for the disease.

Researchers at the University of California-Davis have made some surprising discoveries about the body’s initial responses to HIV infection. Studying simian immunodeficiency virus, the team found that specialized cells in the intestine called Paneth cells are early responders to viral invasion and are the source of gut inflammation produced via a cytokine called interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β).

Though aimed at the presence of virus, IL-1β causes breakdown of the gut epithelium that provides a barrier to protect the body against pathogens. Importantly, this occurs prior to widespread viral infection and immune cell death. But in an interesting twist, a beneficial bacterium, Lactobacillus plantarum, was found to help mitigate the virus-induced inflammatory response and protect the gut epithelial barrier.

The new findings are published in the current issue of the journal PLoS Pathogens.

One of the biggest obstacles to complete viral eradication and immune recovery is the stable HIV reservoir in the gut. There is very little information about the early viral invasion and the establishment of the gut reservoir.

“We want to understand what enables the virus to invade the gut, cause inflammation and kill the immune cells,” said Satya Dandekar, lead author of the study and chair of the Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology at UC Davis.

HIV is part of a family or group of viruses called lentiviruses. Lentiviruses other than HIV have been found in a wide range of nonhuman primates. These other lentiviruses are known collectively as simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). Many SIV’s bear a very close resemblance to HIV-1 and HIV-2, the two types of HIV that affect humans. Thus, SIV’s make for an optimal research model to study the effects of the disease.

There’s more to the immune response than immune cells

In the new study, researchers examined the initial physiological response to SIV infection to see how the virus invades the body and how the immune system responds.

They detected a very small number of SIV infected cells in the gut within the initial 2.5 days of viral infection; however, the inflammatory response to the virus was wreaking havoc on the gut lining. IL-1β was reducing the production of tight-junction proteins, which are crucial to making the intestinal barrier impermeable to pathogens. As a result, the normally cohesive barrier was breaking down.

Digging deeper, the researchers found the inflammatory response through IL-1β production was initiated in Paneth cells, which are known to protect the intestinal stem cells in order to replenish the epithelial lining. “Our study has identified Paneth cells as initial virus sensors in the gut that may induce early gut inflammation, cause tissue damage and help spread the viral infection,” said Dr. Dandekar.

This is the first report of Paneth cells sensing the presence of SIV infection; it’s also the first study to find a link between IL-1β production and gut epithelial damage during early viral invasion. In turn, the epithelial breakdown underscores that there’s more to the immune response than immune cells.

“The epithelium is more than a physical barrier,” said first author Lauren Hirao. “It’s providing support to immune cells in their defense against viruses and bacteria.”

The researchers also found that the addition of a specific probiotic strain, Lactobacillus plantarum, to the gut reversed the damage by rapidly reducing IL-1β, resolving inflammation, and accelerating repair within hours.

The study points to interesting possibilities of harnessing synergistic host-microbe interactions to intervene early viral spread and gut inflammation and to mitigate intestinal complications associated with HIV infection. “Our findings provide potential targets and new biomarkers for intervening or blocking early spread of viral infection,” said Dr. Dandekar.

The team says future research will focus on potential therapies using the newly identified markers. “Understanding the players in the immune response will be important to develop new therapies,” said Dr. Hirao. “Seeing how these events play out can help us find the most opportune moments to intervene.”