The Ebola outbreak in West Africa has taken an unprecedented toll on health care workers, infecting more than 240 and killing more than 120, the World Health Organization said this week.

“The outbreak of Ebola virus disease in west Africa is unprecedented in many ways, including the high proportion of doctors, nurses, and other health care workers who have been infected,” the agency says in its latest update on the outbreak in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone.

On Tuesday, WHO said it pulled workers from one of its own posts at Kailahun in Sierra Leone after a worker became infected. The agency said it will reopen the post after it reassesses safety there. The workers remain in the country, WHO said. “This was the responsible thing to do,” said a statement from Daniel Kertesz, a WHO representative in Sierra Leone. The workers “are exhausted from many weeks of heroic work, helping patients infected with Ebola. When you add a stressor like this, the risk of accidents increases.”

The WHO cites several factors that could help explain the high proportion of infected medical staff. These include “shortages of personal protective equipment or its improper use, far too few medical staff for such a large outbreak, and the compassion that causes medical staff to work in isolation wards far beyond the number of hours recommended as safe,” the report says. Staff members also are overworked, stretched thin and exhausted, which can contribute to mistakes in infection control, WHO says.

Health care systems caught off guard by Ebola outbreak

As the report notes, the current outbreak is quite different from previous ones. Past Ebola outbreaks have occurred in remote areas, in a region of Africa that is more familiar with the virus, and with chains of transmission that were easier to track and break. Furthermore, Ebola infections among health care workers were previously relatively uncommon and usually happened at the beginning of an outbreak, before the virus had been identified; once the virus was confirmed and proper protective measures were put in place, cases among medical staff quickly dropped off.

However, the ongoing outbreak in West Africa has proven to be an entirely different situation.

This is the first time the disease has ever reached this region of Africa; prior outbreaks have been confined to the central and southwestern African nations of Uganda, Gabon, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The three main countries involved in the current outbreak — Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia — and the newly involved country of Nigeria, have never seen the virus. Neither doctors nor the public are familiar with the disease.

The outbreak has swept across a huge geographical area, affecting capital cities as well as remote rural areas. This has vastly increased opportunities for undiagnosed cases to have contact with hospital staff and has made it difficult — at times impossible — to track down the contacts of infected patients. Complicating matters even more is the intense fear that has paralyzed entire villages and cities, resulting in distrust of health workers and non-compliance with the orders of local health authorities. For instance, there are many reports of patients intentionally misleading health care workers to avoid being diagnosed with Ebola and sent to an isolated treatment unit, where they fear they will die. This puts health workers at extreme risk of unknowingly coming into contacted with infected bodily fluids.

In some cases, distrust and fear have spilled over into violence, leading to attacks on health care workers. Back in July, officials from the International Federation of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent described one such incident:

We had an incident in Guéckédou, the epicenter of the outbreak in Guinea recently where people carrying knives surrounded one of our marked Red Cross vehicles.

It is not the first time we have had such an incident, and it likely will not be the last.

The WHO report also notes that several infectious diseases endemic in the region — like malaria, typhoid fever, and Lassa fever — mimic the initial symptoms of Ebola virus disease. Patients infected with these diseases will often need emergency care, and their health care workers may see no reason to suspect Ebola and see no need to take protective measures.

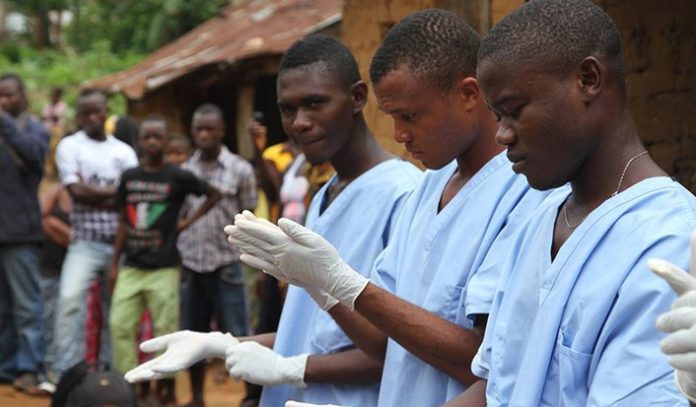

Health workers deliver ‘compassionate care’ despite hostile conditions, high risk of infection

Even after health workers had confirmed that the disease was, in fact, Ebola, the scant public health infrastructure in the affected countries made it impossible to launch an adequate response to the outbreak. “In many cases, medical staff are at risk [for infection] because no protective equipment is available – not even gloves and face masks,” WHO says. “Even in dedicated Ebola wards, personal protective equipment is often scarce or not being properly used.”

Without the use of appropriate protective equipment, health care workers have an extremely high risk of contracting the virus while caring for patients. Human-to-human transmission of Ebola results from direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes) with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected people, and indirect contact with environments contaminated with such fluids. The symptoms of the virus — which include diarrhea, vomiting, and internal and external bleeding — further increase the risk of transmission to caregivers.

Furthermore, even the health workers who have access to protective equipment are still at risk for infection, the report says. Personal protective equipment is “hot and cumbersome, especially in a tropical climate,” which severely limits the duration of time that doctors and nurses can work in an isolation ward. However, WHO says, “[s]ome doctors work beyond their physical limits, trying to save lives in 12-hour shifts, every day of the week.” Staff who are exhausted are more prone to make mistakes, WHO adds.

The report also notes that the “compassionate” style of caregiving practiced by health care workers in the region has contributed to their risk of infection:

Some documented infections have occurred when unprotected doctors rushed to aid a waiting patient who was visibly very ill. This is the first instinct of most doctors and nurses: aid the ailing.

Virus still has ‘upper hand’

The outbreak has “taken the lives of prominent doctors in Sierra Leone and Liberia, depriving these countries not only of experienced and dedicated medical care but also of inspiring national heroes,” the report says.

Among medical workers previously infected in the outbreak were two Americans, Nancy Writebol and Kent Brantly, who were transported from Liberia to Atlanta for care and released from Emory University Hospital last week. Writebol, a clinic aide, and Brantly, a physician, recovered after treatment with an experimental medication called ZMapp. A Spanish priest infected with Ebola also received the drug but died. In addition, a Liberian doctor, Abraham Borbor, died despite receiving ZMapp, Liberian Information Minister Lewis Brown said Monday. It is not possible to know from such anecdotal reports whether the drug helps or hurts, medical experts say.

The heavy toll on health care workers in this outbreak has a number of consequences that further impede control efforts, the report says. First, it depletes one of the most vital assets during the control of any outbreak. WHO estimates that, in the three hardest-hit countries, only one to two doctors are available to treat 100,000 people, and these doctors are heavily concentrated in urban areas. It can also lead to the closing of health facilities, “especially when staff refuse to come to work, fearing for their lives,” WHO says. Furthermore, when hospitals close, other common and urgent medical needs — such as safe childbirth and treatment for malaria — are neglected.

To prevent further spread among health workers, training in proper use of protective equipment is absolutely essential, as are strict procedures for infection prevention and control, the report says.

However, the Ebola virus still has the “upper hand” in an outbreak that has sickened more than 2,600 and killed more than 1,400, says Dr. Tom Frieden, the director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Frieden is visiting the outbreak area and spoke Monday in Liberia, expressing optimism that the outbreak can be contained.

“Ebola doesn’t spread by mysterious means, we know how it spreads,” he said in remarks broadcast on Liberian TV. “So we have the means to stop it from spreading, but it requires tremendous attention to every detail.”

The outbreak in West Africa is the largest ever and will cost $430 million to control, according to a draft WHO report obtained by Bloomberg news.

Meanwhile, what appears to be a separate outbreak may be happening in the Democratic Republic of Congo. On Sunday, government Health Minister Felix Kabange Numbi said Ebola had killed 13 people there, including five health care workers. Initial tests showed a different strain of the virus than the one spreading in the other countries, he said.