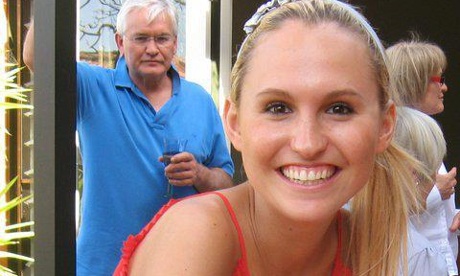

Staff at NSW hospital did not notice 23-year-old was missing more than two hours after she walked out of centre

In a case he described as complex and harrowing, a New South Wales coroner has found mistakes and a lack of documentation by staff at the Wesley eating disorders centre did not cause the death of a 23-year-old woman receiving treatment there.

In July 2011, Alana Goldsmith killed herself after walking out of the clinic at Wesley hospital in Ashfield. Staff did not realise she was missing for more than two hours, and she was found dead a short time later.

In his report released on Monday, coroner Mark Douglass found poor documentation and a failure to obtain discharge summaries for her previous spells in hospital – which disclosed an earlier suicide attempt – had reduced Goldsmith’s level of care.

“Such information may have changed her [suicide] risk category within the Wesley eating disorder clinic and may have led to more supervision and potentially an intervention in the planned suicide,” he found.

But Douglass also found the failures by the centre did not lead to Goldsmith’s death, and emphasised anorexia nervosa was an insidious and difficult disease that had led to her suicide.

“The unpredictable nature of suicide makes prevention difficult,” he found.

“The mistakes and failures at Wesley eating disorder clinic did not lead to Alana’s death. The failures and mistakes represent a loss of an opportunity for intervention that may or may not have prevented the death.”

He said the evidence was clear that anorexia nervosa, which Goldsmith had suffered from for nine years, was a mental illness that had contributed to her suicide.

“It is likely that she could no longer endure the burden of living with her mental condition, anorexia nervosa,” Douglass said.

It was an illness that “ravages the body and the brain, articulating it as a very insidious and debilitating mental illness/condition”, he said.

A Wesley Mission spokesman, Graeme Cole, said the hospital would review the findings and recommendations from the inquest in detail.

“We know this is a difficult time for all concerned,” he said. “We have been, and continue to be, deeply saddened by the death of Alana Goldsmith and extend our deepest and heartfelt sympathies to her family and those who knew her.”

Goldsmith’s sister, Simone, said on Monday her family had initially felt relieved when Alana was admitted to the Wesley centre.

“It felt like a miracle that a bed was available immediately because there was a five- to seven-week wait list at Northside clinic, where Alana had three prior admissions,” she said.

“We had faith that the experts would care for her and put her back on the long road to recovery. In hospital there was hope. The hospital would be a safe haven. But that wasn’t to be the case.”

Her mother, Judy, said she was grateful the coroner had recognised some of the failings in care to Goldsmith.

“These failings raise serious concerns,” she said. “We believe that patients who admit voluntarily to a mental health unit should be kept in a safe environment with a level of vigilance appropriate to their assessed level of risk.

“Regardless of that risk, eating disorder sufferers require regular and effective monitoring, and for the critical period immediately after meals or snacks they require constant monitoring in a group environment by properly qualified and trained staff.”

Anorexia is the most lethal of all psychiatric disorders. The latest available figures show 914,000 Australians suffered from an eating disorder in 2012, and more than 1,800 died from an eating disorder in the same year.

The chief executive of eating disorder support group the Butterfly Foundation, Christine Morgan, said the coroner’s findings provided a pivotal opening to recognising eating disorders as a leading cause of suicide.

Goldsmith’s case would raise awareness and compel changes to care, she said.

“Alana’s death was tragic,” Morgan said. “Tragically, she was under the care of a specialist eating disorders hospital team at the time.”

She said the federal government must support state and territory governments to make sure there were adequate treatment facilities, in both hospitals and in the community, with eating disorder specialists employed.

There also needed to be an expanded trained workforce able to identify and treat eating disorders, she said.

“The coroner findings reflect the disastrous and heartbreaking statistic that 20% of all people suffering an eating disorder will die,” Morgan said.

“The coroner’s inquiry placed a bright spotlight on the deadly nature of eating disorders, giving Australia an opportunity to tackle the devastating impact eating disorders are having on our community.”

- Readers seeking support and information about suicide prevention can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467