The Senate’s Community Affairs References Committee on Friday published its findings on out of pocket costs in Australian healthcare, saying that imposing additional costs would make it harder for people, particularly in vulnerable groups to access primary care, which would not only be at the cost of their own health but to the whole system,

See this report from The Sunday Age for more details, and the committee’s full report, and recommendations below.

Coalition members of the committee provided a dissenting report.

Also last week the Australian Medical Association (AMA) finally unveiled its compromise plan to little acclaim from public and consumer health advocates, nor from the government or cross benches.

See an analysis below from The Conversation of the AMA proposal, which notes that it provides additional protection to children and concession-card holders, but still risks major inequity and low-income people falling through the safety net cracks and “seems to contribute to the general practice bottom line rather than the government budget position”.

In other responses, the Australian Indigenous Doctors Association (AIDA), said the AMA plan does nothing to address the acknowledged financial impact of the proposed co-payment on Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander community-controlled health services.

“The Federal Government’s co-payment plan has been universally rejected by the Indigenous health sector because we know that any co-payment will provide a disincentive for our people to visit a GP and we have spent the past decades working hard to encourage our peoples to visit doctors; the original proposal and the AMA’s plan both fly in the face of all the evidence.”

The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) said exempting concession card holders from the co-payment would “not fix what is poor health policy”. It reiterated calls by community and health groups for the Government to consult not just with the AMA.

“We would like to see the Government abolish both co-payments altogether or at least have a transparent consultative process so they get a full understanding of impacts of these dangerous policies.”

The Council of The Ageing also said the AMA proposal would still leave many older Australians out of pocket and reluctant to seek the health care they need.

“There will be many tens of thousands of older Australians who may not quality for a concession card, and thus be excluded under the AMA policy, but are still on very low incomes or even unemployed but not on Newstart.”

Finally, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare also provided evidence of the costs of inequity, with its report: Mortality inequalities in Australia 2009–2011. It found:

“Despite relatively high standards of health and health care in Australia, not all Australians fare equally well in terms of their health and longevity. Substantial mortality inequalities exist in the Australian population, in terms of overall mortality, and for most leading causes of death, and these inequalities are long-standing.”

***

Jane Hall and Kees Van Gool write:

AMA co-pay plan: protecting the poor and GPs’ bottom line

Bulk billing without restrictions has been a feature of the Australian health system since the introduction of Medicare in 1984. It is particularly important in general practice, as it means any Australian can see a primary care doctor without having to pay out-of-pocket costs. In 2012/13, 81% of GP consultations were bulk billed.

The 2014 budget introduced the notion of a co-payment to apply to the first ten GP visits. This has been one of the more unpopular budget measures, largely on the basis of the effect on the disadvantaged. The AMA today released its awaited alternative.

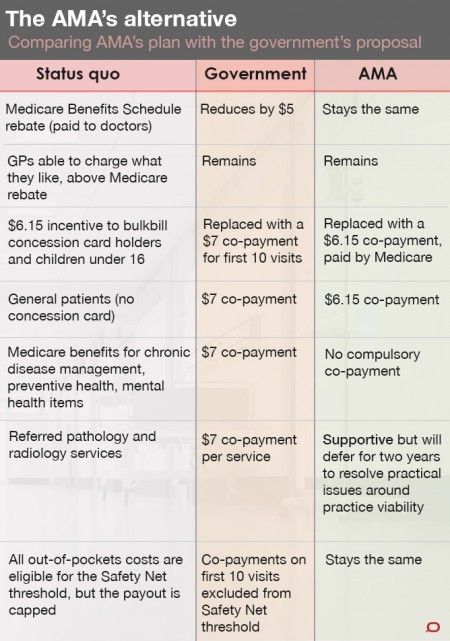

So how does the Australian Medical Association (AMA) plan compare with the government’s?

As the table shows, it retains the notion of a co-payment, but only for general patients and only as long they are not receiving chronic disease management, services of a preventive nature, or mental health care. In other respects, it sticks with the status quo.

Around half of all GP visits result in further treatments such as pathology and imaging services, which will incur further co-payments under both the AMA and Government proposals; although the AMA has recommended deferring the introduction of these by two years.

So, does the AMA plan protect the disadvantaged while sending a price signal to the people with the means to contribute more to the costs of their health care? And is it an alternative way for the government to reach its objectives?

Around 5.5 million Australians hold some type of concession-card. Eligibility largely depends on age, income and circumstances. These people will be protected from any new co-payments (not all card holders are bulk billed now).

But differences in eligibility criteria suggest that there are plenty of relatively poor families who do not qualify for a card, whereas many relatively wealthy retirees do.

In order to qualify for the low-income health care card, for example, a single parent with one child can earn a maximum of around $47,000 per year, whereas a couple of retirement age can earn a maximum of $80,000 per year, face no asset test, and still qualify for the seniors health care card.

This shows the concession card is a very blunt instrument to determine the ability for patients to pay for their health care, and without the option of bulk billing, more low-income people will fall through the safety net cracks.

Over 72% of all bulk-billed items are provided to children aged under 16 or concession-card holders. The vast majority of those without a concession card are not bulk-billed and already face co-payments to visit their GP. When they do, they pay, on average, $28.58 after the Medicare rebate, or over $60 at the visit for most consultations.

For the vast majority of these people, the proposal will have no effect as they already incur a co-payment well in excess of the minimum co-payment of $6.15 that has been proposed by the AMA.

Indeed, the AMA’s proposed price signal for GP visits is only likely to affect those Australians who do not have a concession card and who currently visit a bulk-billing GP (or one who charges less than the proposed minimum co-payment).

The rationale for the introduction of a $7 co-payment has been confused, and three reasons have been advanced: the need to reduce Medicare expenditure; the need to contribute to the budget bottom line; and the need to establish a price signal which will increase the efficiency of health care service delivery.

Medicare expenditure can be reduced by reducing rebates or reducing use. The government proposal aimed to do both.

Evidence shows that price signals discourage use by the disadvantaged, but also that reducing primary care use has not resulted in long-term cost savings to the system.

Under the government proposal, increased revenue from co-payments was not directed to the budget deficit but to a medical research fund. This would reduce government debt as it only the interest was to be returned to research.

The AMA proposal, while providing additional protection to children and concession-card holders, seems to contribute to the general practice bottom line rather than the government budget position. Doctors would be better off and according to Health Minister Peter Dutton, the AMA plan would wipe out 97% of the government’s $3.5bn savings.

The efficiency of the health system and its long-term sustainability is worth attention. But Australia does not have an immediate fiscal crisis due to health expenditure. It’s time to design a system of delivering health care that addresses 21st century health problems with 21st century technologies and knowledge.

Jane Hall is Professor of Health Economics and Director, Centre for Health Economics Research and Evaluation at University of Technology, Sydney.

Kees Van Gool is a health economist at the University of Technology, Sydney.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. A reminder to Croakey readers that TC articles are freely available for republishing under a Creative Commons license.