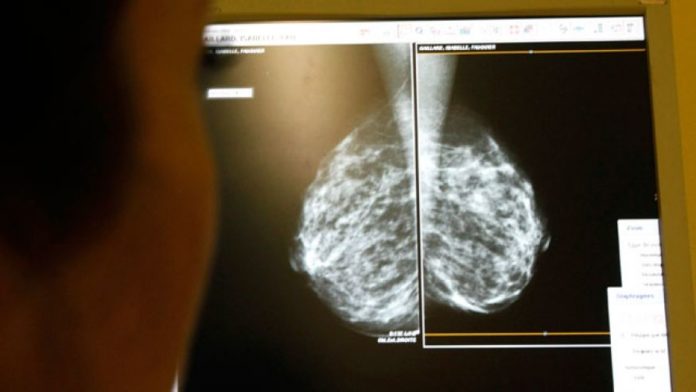

Women whose screening mammograms produce false alarms have a heightened risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer years later, but the reason remains mysterious, researchers say.

An increased risk of breast cancer among women with a “false positive” mammogram has been reported before. What’s different about this new study is that the authors tried to figure out how much, if any, of the extra risk is simply due to doctors missing the cancer the first time they investigated the worrisome mammogram findings.

But mistakes from doctors missing cancers explained only a small percentage of the increased risk, according to lead author Dr. My von Euler-Chelpin, an epidemiologist from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

She says the explanation for most of the increased risk of later breast cancer in women with false-positive mammograms remains a mystery. (A mammogram is considered false positive when it suggests possible breast cancer but additional screenings or a biopsy fails to find it.)

Of more than 58,000 Danish women who underwent screening mammography between 1991 and 2005, the new analysis identified 4,743 women with suspicious findings that were eventually declared negative.

By 2008, 295 of those 4,743 women had been diagnosed with breast cancer, Dr. von Euler-Chelpin and colleagues report in the journal Cancer Epidemiology.

Radiologists reread the original mammograms and found that doctors had actually missed the cancer in 72 of the 295 women, for a false-negative rate of 1.5 percent. Even after taking those missed cancers into account, however, the researchers found that women with false-positive mammograms were still 27 percent more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer years later, compared to women with only negative test results.

The risk was slightly higher in women who had surgical biopsies that turned out to be negative.

Need for personalized mammography guidelines

The excess rate of breast cancer among women who have had false-positive mammograms points to the need to personalize screening programs for women, says Dr. von Euler-Chelpin. She wonders if women who get false-positive mammograms should be followed more closely by their doctors, or if false-positive patients should be screened differently.

Although having had a false-positive mammogram is associated with a woman’s breast cancer risk, Dr. von Euler-Chelpin points out that the actual risk of being diagnosed with breast cancer remains low.

The average five-year breast cancer risk for a 50-year-old white woman with no prior family history of breast cancer is 1.25 percent. It ranges from less than 1 percent, to 2.70 percent, depending upon breast density, for the same woman with a history of a prior breast biopsy, regardless of whether the biopsy was positive or negative.

“This paper is one little step on the way of trying to identify high-risk groups,” says Dr. von Euler-Chelpin. “The goal is to find more personalized screening programs for women.”

The American Cancer Society recommends that women be screened for breast cancer every year they are in good health starting at age 40. But a growing number of researchers have questioned the benefits of annual mammograms, and since 2009 the government-backed United States Preventive Services Task Force has recommended that screening be done every two years and be generally restricted to women aged 50 to 74.

Women in Denmark between the ages 50 to 69 are advised to have screening mammograms every other year.

According to a 2013 study assessing the impact of screening frequency on breast cancer diagnoses, getting a mammogram every other year instead of annually does not increase the risk of advanced breast cancer in women ages 50 to 74.

The recommendation to reduce the frequency and delay the start of mammography screening was based on research showing the risk of false-positive results – which needlessly expose women to the anguish of a possible breast cancer diagnosis and the ordeal of further testing – outweighed the benefits of detecting cancers earlier.