A biotech greenhouse associate replaces young tobacco plants of a unique strain in the greenhouse at Medicago USA, Inc.

A biotech greenhouse associate replaces young tobacco plants of a unique strain in the greenhouse at Medicago USA, Inc.

The media has been buzzing about ZMapp, widely reported as an experimental top-secret, untested Ebola serum. But what is it? A look into the treatment reveals the marvels of biotechnology — and its limitations.

ZMapp is not a cure or a vaccine. It’s a cocktail of genetically engineered antibodies that boosts a patients’ ability to fight off Ebola. ZMapp actually combines two different serums made by two different companies.

The first serum is called MB-003, and was developed by San Diego firm Mapp Biopharmaceutical. The second goes by the name ZMAb, and was made by Canadian company Defyrus Inc.. When Mapp Biopharmaceutical’s commercial arm LeafBio combined the two, MB-003 plus ZMAb became ZMapp.

Antibodies are one of the body’s main defenses against viruses and bacteria. When we get sick, our immune system produces antibody cells to tear apart the invaders, and restore us to health.

Ebola is deadly because it disrupts the human immune system. Researchers recently discovered exactly how the virus impairs antibody production.

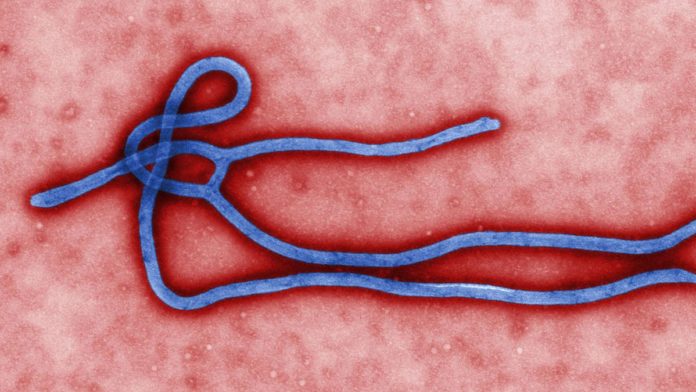

Created by Center for Disease Control and Prevention microbiologist Cynthia Goldsmith, this colorized transmission electron micrograph (TEM) reveals some of the ultrastructural morphology displayed by an Ebola virus virion.

Development of MB-003

An August 2013 Mapp Biopharmaceutical research paper explains how MB-003 was made, and shows its efficacy in treating Ebola in monkeys. The company has been working with the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) on an Ebola treatment, in response to government fears that the virus could be used as a bioweapon.

A doctor for tropical medicine prepares a blood sample for analysis during a demonstration of Ebola-treatment capabilities at Station 59 at Charite hospital on August 11, 2014 in Berlin, Germany.

Image: Sean Gallup/Getty Images

The first step was for scientists to inject Ebola into mice, and extract three types of antibodies that fight different parts of the virus. It’s impossible to inject mouse antibodies into humans because the latter’s immune system will attack them as foreign invaders; so scientists spliced in human DNA to produce chimera antibodies acceptable to humans. The result was a serum they called MB-003.

The next challenge was producing enough MB-003 for an effective dose. Previous studies found that antibodies could be grown inside genetically engineered Nicotiana Benthamiana, an indigenous Australian tobacco plant, which has also been used to grow West Nile virus antibodies.

Plants make good hosts because they do not carry viruses that can infect humans, and are cheaper than mammals. Researchers also discovered that plant-grown Ebola antibodies are more effective than those grown inside the ovaries of Chinese hamsters, according to Mapp Biopharmaceutical’s study.

Next, Mapp Biopharmaceutical tested the MB-003 serum on monkeys. Rhesus macaques were injected with Ebola, samples of which were provided by the USAMRIID. One or two days after infection, the monkeys received an intravenous infusion of MB-003. Forty-three percent of the infected monkeys survived.

Development of ZMab

Defyrus developed its serum ZMAb in a similar way. ZMAb also contains three antibodies derived from mice, and has been tested in Rhesus Macaques.

In June 2012, Defyrus tested ZMAb in Rhesus Macaques, and found that 100% of infected monkeys survived when treated 24 hours after exposure. Fifty percent survived when treated 48 hours after exposure.

A November 2013 Defyrus study showed that ZMAb offered extended protection against the virus. Scientists reinfected surviving monkeys 10 weeks after their first infection, and 100% survived. What’s more, four out of the six monkeys reinfected 13 weeks after initial exposure survived.

ZMapp’s origins

Mapp Biopharmaceutical and Defyrus both licensed their serums to Mapp Biopharmaceutical’s commercial arm, LeafBio, which combined the two to make ZMapp.

Before ZMapp could begin human trials and get approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the Ebola outbreak began in Guinea when Patient Zero died in December 2013. Since then, the disease has claimed 1,145 lives, according to the World Health Organization.

Two American doctors were infected with Ebola through their work in a Liberian hospital with the U.S. aid group Samaritan’s Purse. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writbol recovered after receiving ZMapp. However, it’s unclear whether the drug helped, or if they are getting better on their own. Around 40% of people infected with Ebola are surviving the current outbreak.

American Ebola patient Dr. Kent Brantly: “I am growing stronger every day” http://t.co/NA8EPv0pYA pic.twitter.com/uPPg70NkEm

— Mashable (@mashable) August 8, 2014

The WHO said last Tuesday that use of ZMapp is “ethical,” despite the fact that it has never been previously tested on humans.

However, the serum’s supply has been exhausted, according to a Defyrus’ website. A ZMapp information sheet released by LeafBio and Mapp Biopharmaceutical explains that “very little of the drug is currently available” because it has not been evaluated for safety in humans.

To gain FDA approval, a drug must undergo three stages of human trials, which means ZMapp is likely years away from FDA approval.

“Mapp and its partners are cooperating with appropriate government agencies to increase production as quickly as possible,” LeafBio said in a statement on its website. Currently, it’s unclear how long it will take to manufacture more of the serum.