Autism is something that happens because of vaccinations.

Autistic people are like Rain Man.

Autism is overdiagnosed.

Autism only happens to other people’s kids.

Your son can’t be autistic. He’s so friendly.

* * *

I remember when I first saw those multicolored puzzle piece car magnets. I knew they stood for autism spectrum disorder awareness. Which bugged me. Everything was autism. Have a weird kid? Diagnose him with autism. Don’t have a name for what is going on with your child? Throw her under the umbrella of autism. Doesn’t everyone know someone who is a little weird? Won’t look you in the eye? Has odd social skills? Why is it all autism all of a sudden, is what I used to think.

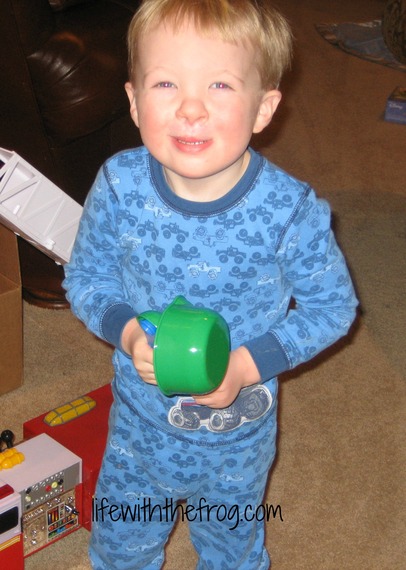

But the more I saw those puzzle piece magnets, the more I thought about my own child and what a puzzle he was. Such a unique child. No way to describe him. I began to wonder if maybe he would fit under the umbrella.

I asked his early childhood special education preschool teachers, who worked with children far more severe than Slim. “Oh no,” they said, “we have kids who are way worse than he is. He is not like them at all.”

But what about the way he insisted on carrying the same set of orange spoons with him everywhere he went? “Other kids do that, too,” someone told me.

What about the way he memorized songs and cartoons, books and commercials, and repeated them all day long? “You used to do that, too, Kathy,” my mom told me.

What about the way he walked the perimeter of a room during a party and never engaged in a conversation until he was ready to tell someone something? Then he talked “at” them and walked away. “He’s just getting comfortable. At least he talks to people. Autistic kids never talk to people.”

I asked. I asked the pediatrician, the kindergarten teachers, his speech teacher, anyone and everyone who worked with him. They all said, “No, he’s not autistic.”

The other kids loved him. They thought he was funny when he talked about sharks all the time and knew everything there was to know about China.

But he had no real friends, and he didn’t get asked on playdates. People looked at us weirdly. He couldn’t stay focused during a swimming lesson or golf lesson or tennis lesson. Other people who didn’t know him said he was autistic.

It broke my heart. And made me mad.

But it also made me wonder, “If they know, how can the people who are supposed to know him best not know?”

Things got harder as he got older. There were behaviors at school and at home that we didn’t know how to deal with. He wasn’t getting along with his brothers or understanding consequences or transitioning easily into school. He “leaned in” rather than hugging.

I used to think that because of his birth defect, he was getting all the therapy he would get if he had a diagnosis anyway. I didn’t want him to have a “label.”

Soon I began to think, if that label could help him, maybe he should have it. It was nothing to be ashamed of, right? If he could get training and therapy that would help him assimilate more easily, but still keep his wonderful uniqueness, that would be a good thing, right?

But even a doctor who specialized in autism was stumped as to whether he was or wasn’t until he finally said he was. Slim was 10 years old.

And then we met some other families in social skills class who talked about their autistic sons, and things became clear: they were like Slim. They had trouble making friends and sleeping and understanding consequences and they knew everything about something, too.

We finally understood it and accepted it and were OK with it, this high functioning autism. His quirkiness had a name.

And listening to the other parents, I finally understood that he wasn’t weird — he was unique and special and awesome and wonderful and interesting. We wanted him to be the best uniquely specialized, awesomely interesting and wonderful person he could be. He just needed more help than some people do.

When I told people about his social skills class, so many other moms told me their child could benefit from knowing those skills, too.

Which makes me think that people with autism aren’t so different from the rest of us after all. Don’t we all have our quirks and preferences? Don’t we all have things with which we struggle?

Is autism overdiagnosed? Underdiagnosed? I don’t know. But what is becoming clear is that there are not enough services and opportunities for these kids to fully become who they are. And it makes me sad.

Because who they are IS this wonderful multi-colored puzzle, full of interesting ideas and complexities that most of us will never even know.

Is he autistic? Yes, he is. And it makes life so much more interesting.

This piece is part of a series of essays on what autism looks like for different families. It originally appeared on Kissing the Frog.