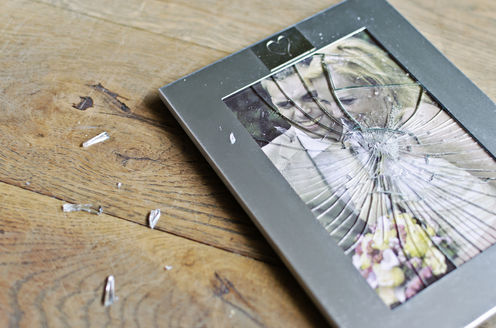

The term “domestic violence” typically conjures images of physical assaults perpetrated by men against women and children in the home. But beneath the tip of the iceberg of severe violence lie a myriad of other damaging behaviours, including psychological and financial abuse, and emotional manipulation.

These are the less “visible” forms of abuse, but should not be overlooked or trivialised simply because their effects are less easily seen. To truly address family violence we need to target all forms of violent and abusive behaviour irrespective of who commits it.

Violence

Intimate partner violence occurs in relationships irrespective of age, sexual orientation, gender, income or ethnicity. Research shows that adolescents, young people and adults are victimised in intimate relationships, and domestic violence is observed in both same-sex and opposite-sex relationships.

The nature of intimate partner violence appears to differ in important ways in relation to gender.

Women are more likely than men to experience serious physical assaults that result in injury, and are more likely to be subjected to such acts on a recurrent basis. And in cases of family homicide, women are over-represented as victims compared to men. This pattern is also evident for severe (but non-lethal) physical assaults.

But when it comes to other forms of violence, such as being slapped, pushed or shoved by a partner, throwing an object, or being hit by an object, international research shows that roughly equal proportions of male and female partners engage in intimate partner violence.

Other forms of abuse

Australian data is not available, but Canadian research also indicates that the rates of emotional manipulation by a partner do not differ substantially according to gender.

Emotional abuse can involve coercive control (creating an atmosphere of fear or intimidation), humiliating or degrading the partner, monitoring their behaviour, and making threats to harm loved ones. Other forms of non-physical forms of abuse include financial control.

These types of abuse may not cause physical harm, but are damaging nonetheless. People’s self-confidence becomes shattered, anxiety levels rise, and feelings of learnt helplessness ensue. Unsurprisingly, it is often the case that physical violence co-occurs with other non-physical forms of control and abuse.

What do we know about the perpetrators?

Popular culture suggests that the “profile” of a domestic abuser can be captured by a checklist of key characteristics, such as jealousy, control, manipulation, deception and charm. While these features are present in many cases, the “possessive partner” stereotype is too simplistic.

A complex range of attributes and circumstances contribute to someone acting in a violent or abusive manner. These include:

- Witnessing or experiencing family violence as a child

- Personal, cultural or peer beliefs that support the use of aggression or violence

- Poor language (verbal) skills, which can dispose people to resolving disputes or managing their frustration with fists rather than words

- Alcohol and drug use, which can lead people to act more aggressively

- Mental health problems, such as depression or chronic stress

- Dysfunctional personalities

- Financial difficulties and other stressors.

Many of these characteristics can be modified in treatment or other behaviour change programs, which is often the most successful way of bringing the violence to an end.

What do we know about the victims?

Women and men who are subjected to intimate partner violence report a range of mental and physical health problems, chief among them fear and anxiety, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress, such as feeling emotionally numb, detached from others, and hyper-vigilant.

Many victims also report increased alcohol or other substance use to help them deal with their distress.

Research shows that the more frequent or recurring the abuse, the greater the mental health impacts. Thoughts of suicide are not uncommon for victims who may perceive no other means to escape their abuser.

The effects of recurring victimisation within an intimate relationship can also damage the victim’s social or occupational functioning. Many Australian workplaces have formalised policies or procedures to deal with family violence and to better support employees who are victims of this crime.

Not just a ‘domestic’ issue

Terms such as “domestic violence” have not been helpful since they inadvertently connote that the behaviour is not the business of others. To protect those at risk of harm, we need to move away from the notion that violence within intimate partnerships and families is somehow a private matter.

As a mature society, we must give a clear message that violence and other types of abuse within families – as with other areas in society – must be eradicated. Only with ongoing dialogue, research, and effective strategies and interventions can we begin to tackle this problem.

The National Sexual Assault, Family & Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

Read the other articles in The Conversation’s Domestic Violence in Australia series here.

Rosemary Purcell receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

James Ogloff does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.