A LAKE Macquarie doctor who performed transplants of sexual glands from monkeys to humans in the 1930s features in a new book that seeks to recognise his medical achievements.

Dr Henry Leighton-Jones retired to Eraring in 1928 and began to study endocrinology, a branch of medicine concerned with glands and hormones.

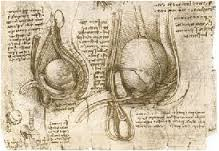

In the 1930s, he grafted glands of monkey testicles and ovaries onto the same body parts in humans.

Some believe he was seeking ‘‘the fountain of youth’’.

Author Doug Saxon documents aspects of his life inA History of Eraring and its School.

Mr Saxon, of Fishing Point, said the doctor’s work had made many headlines over the years.

‘‘I tried to give a balanced account and put his work in perspective,’’ Mr Saxon said

Mr Saxon said ‘‘people sometimes put a 21st century spin’’ on the matter, but the doctor was ‘‘a pioneer in his field’’.

His book contains a Newcastle Herald article from 1939, in which the doctor ‘‘refutes the notion that his work and that of his mentor, Russian Serge Voronoff, was primarily sexual’’.

‘‘He thinks that everyone should be able to attain 100 years of age,’’ Dr Leighton-Jones was reported as saying of his mentor.

Mr Saxon said monkeys were kept in a cage on the doctor’s Eraring property and operations were done at a small hospital in Morisset.

In the book, he quotes an account of the doctor’s life written by Dr Herbert Copeman and published in the Medical Journal of Australia in 1977.

The article said Dr Leighton-Jones was ‘‘a well educated and very experienced doctor, dentist and pharmacist’’.

‘‘He took twice the average time to see patients and had a reputation for great skill and care and in the use of his hands and eyes in dentistry and surgery,’’ it said.

He had been the chief medical officer in the Northern Territory, before moving to Eraring.

‘‘He became obsessed with the desire to help cretins, and others thought to be deficient in hormones, including those who were prematurely senile or impotent,’’ the article said.

He went to Paris to study gland-grafting with Dr Voronoff, who ‘‘had been doing transplants from chimpanzees to humans since 1920’’.

‘‘Between 1931 and 1941, he [Dr Leighton-Jones] performed four thyroid grafts on cretins, one of which was regarded as at least temporarily very successful.

‘‘He performed half a dozen ovarian grafts, once using the ovary of a pregnant monkey, and about 30 testicular grafts on patients aged between 24 and 72.’’

Dr Voronoff did a graft on Dr Leighton-Jones in France in 1929.

The Herald article from 1939, when Dr Leighton-Jones was 70, said ‘‘there is about him the keenness of mind [and] verve of a man in his 40s’’.

Dr Leighton-Jones died age 74 on October 24, 1943, on the day he was to present a paper outlining his work at a postgraduate seminar at Newcastle Hospital.

He attended the meeting but died of a heart attack before his paper could be presented.

He was considered to have discovered important principles of tissue typing, which involves transplant donors and recipients being tested for compatibility prior to surgery.

Dr James Le Fanu, a British columnist and historian of science and medicine, has written that Dr Voronoff’s work was a precursor to injections of growth hormone and testosterone.

While some dismissed the monkey grafts as ‘‘the methods of witches and magicians’’, most who had the procedure ‘‘reported a remarkable improvement in well-being’’, he wrote.

‘‘In November 1991, an editorial in The Lancet suggested that the file on Voronoff’s work be re-opened and in particular, that the Medical Research Council should fund further studies on monkey glands.’’

Source: The Herald