Elizabeth Elliot writes:

If a visit to Christmas Island sounds like fun, think again. A remote tropical island in the Indian Ocean – billed as a birdwatcher’s paradise and a haven for snorkelling – has a dark side. It is “home” to 1102 detainees seeking asylum, including 174 children; many are infants and 26 boys are unaccompanied minors.

Having attempted to travel to Australia by boat and been intercepted after July 19, 2013 (the date of a change in immigration policy), these people are being forcibly detained in one of Australia’s immigration detention centres, with the promise that they will never be settled on the Australian mainland. Following the anniversary of one year in detention, tensions are soaring.

I was invited to accompany the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) president, Professor Gillian Triggs, and her team to the Immigration Detention Centre on Christmas Island in July.

The visit was part of the 2014 National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention.. It was prompted by increasing reports of self-harm by mothers with young children.

Mental and physical symptoms of distress

As a paediatrician, my role was to interview children and families, to visit their accommodation and to give an opinion about the impact of detention on their lives – their health and their mental health. Parents described their children as being “always sick”. Certainly most had a respiratory virus during our visit.

Young children are vulnerable to infection and the cramped living conditions on the island promote the spread of infection both within and between families. Many reported ongoing wheeze – asthma – likely exacerbated by both recurrent infections and the constant air-conditioned environment. Some children had waited months for transfer to the mainland for specialist care, including surgery.

Most distressing, however, was people’s heightened emotional state.

We interviewed more than 200 people and two weeks later I am haunted by their words.

“My life is really deth” wrote one 12-year-old girl who had been physically abused in her homeland and whose mother had self-harmed in detention. She had not eaten or spoken for three days and was threatening self-harm.

I wont to die becous in deth I know I can’t live in here any more. If I go back to xxxxx I know they wil kell me and kell my family.

Intent to self-harm is of great concern. Immigration department data confirm that 128 children engaged in actual self-harm in the “onshore” detention network, which includes Christmas Island and the mainland detention centres, between January 1, 2013, and March 31, 2014.

Many of the children we met were anxious and had signs of both post-traumatic stress disorder and current distress. We saw children who described intrusive flashbacks and nightmares, children who had started bed-wetting or stuttering, children who were refusing to eat and drink and children who had stopped talking.

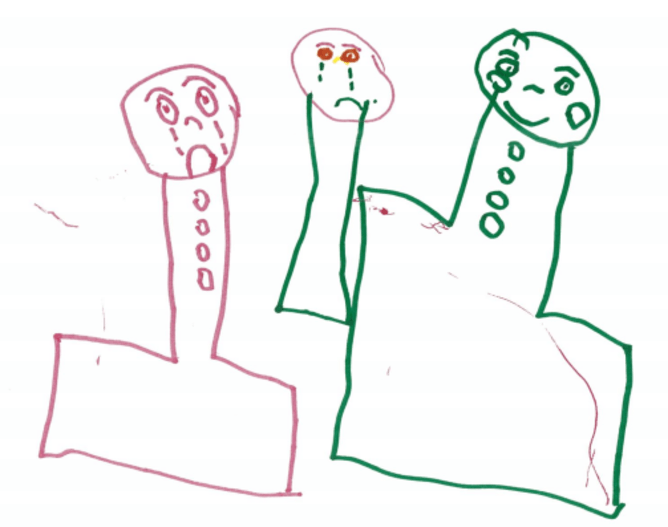

Some expressed their mood through their drawings. In the drawing below this five-year-old girl, whose mother had self-harmed, described (from left):

My Mum only crying, me crying because I don’t have friends and I don’t like staying in Christmas Island, and Daddy.

Children often described traumatic situations in the country they had fled (see drawing below by a 16-year-old unaccompanied minor).

Author supplied

Many described their situation as “hopeless”, claiming they saw “no future”. In the words of one unaccompanied minor, aged 17:

We are very sad because of I’m in detention. Is there anybody in Australia who can help us. Please help us.

During our visit the distress among detainees was palpable. It was expressed as overwhelming sadness and hopelessness, and manifest most dramatically by the high prevalence of self-harm in young mothers and psychological symptoms in their children.

Although this was my first visit to Christmas Island, colleagues who had visited previously were shocked by this change in mood, which Triggs described as a “very significant deterioration”.

Only release from incarceration can ease the harm

We did witness some change on the horizon: a playground under construction, a playroom equipped with toys (this had not yet been used and because of the large number of children on the island access will be rationed), a shade cloth over a play area, and a school soon to be opened. Perhaps these improvements are too little, too late.

Forced detention of children on Christmas Island is no longer a humane option. It is time to move families with children and unaccompanied minors into community detention on the mainland, where they will have freedom of movement and ready access to the services that are their right. These include specialised health and mental health care and education. We cannot keep these people in limbo any longer.

As dictated by international law, we are obliged to make an assessment of their claims for refugee status. We will not curb the escalating rates of mental ill health until assessment of their refugee status is expedited. Under international law we cannot return them to the country from which they have fled persecution and regardless of the result of their assessments they must be given some certainty of their fate.

Life without certainty – wherever that might be – is intolerable.

Elizabeth Elliott is professor of Paediatrics and Child Health at the University of Syndey.presented the findings of her visit to Christmas Island in a submission to a hearing in Sydney yesterday of the Australian Human Rights Commission National Inquiry into Children in Immigration Detention.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.