The Mississippi baby, in remission for over two years, recently experienced HIV rebound. This low – if it can be called that – shouldn’t dampen our hopes for a cure

It was a sad and disappointing turn of events: the child known as the Mississippi baby, in remission of HIV infection for more than two years after discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), now has clear evidence of HIV rebound. The announcement will undoubtedly be viewed by some as a setback in the renewed quest for an HIV cure.

It doesn’t need to be. We need to take the highs and lows in our stride. We have a proof of concept that a cure for HIV is possible in the Berlin Patient, Timothy Brown, who received a bone marrow transplant and remains virus free off treatment for over six years.

We also have the case of the French Visconti cohort, now comprising 20 HIV-positive people who were treated very early with HIV drugs, but then stopped treatment. After almost 10 years off therapy, they are keeping the virus under tight control.

Only one person, who is now in remission for a non Aids-related cancer, reinitiated ART despite his HIV infection still being controlled at the time that he received anti-cancer therapy.

The lows – if the Mississippi baby case can be called a low – provide major insights into the scientific challenges that lie ahead for the researchers, scientists and others gathering at the Aids 2014 symposium in Melbourne this week.

Similar to the Mississippi baby, the Boston patients – two men who received bone marrow transplants that appeared to rid them completely of HIV – also relapsed, and are now back on antiretroviral treatment.

What has been most encouraging for all three patients was that the time the virus stayed under control off treatment, or in remission, was significantly longer than what we have ever witnessed before. The Boston patients were virus-free for 12 and 32 weeks, and the Mississippi infant virus-free for a remarkable 27 months.

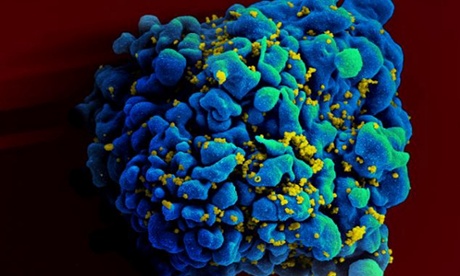

However, as we have learned over the past three decades, HIV has many tricks up its sleeve.

An minute amount of virus – which none of our current tests are even close to detecting – was able to persist in these three patients and reappear at any time, with absolutely no warning.

The Mississippi baby, and the Boston patients, tell us that to achieve long term HIV remission we will likely need to tackle the problem on multiple fronts – lowering as much as possible the number of long-lived, latently infected cells present in the body, as well as bolstering the host defence. One cannot be done without the other.

We’ve always known that the search for an HIV cure wasn’t going to be easy. We must be optimistic, and hope that cases like the Mississippi baby will prove to be another piece in the jigsaw puzzle that is an HIV cure.

To reach this goal will require substantial academic collaboration as well as public-private partnerships that can drive innovative and well-funded strategic research over the long term.

We must continue the search for an HIV cure. We owe it to the 35m people living with HIV.